To Build a Fire

It had been the wettest January in memory in southeastern Georgia. In the manager’s cabin in the Nature Conservancy’s Moody Forest, Carl Seielstad gathers his students on the last full day of their two-week trip. Despite the miserable weather, a whiteboard on the wall tallies the successes of the service-learning course: Moody Unit 1, 60 acres burned. Unit 1 West, 120 acres burned. Broxton Rocks Unit 1, 115 acres burned. Broxton Rocks Unit 16, 400 acres burned. But the conditions for fire have steadily degraded after the 400-acre burn on the fifth day, and the students from the University of Montana College of Forestry and Conservation—here to get hands-on experience in a prescribed burning practicum—have spent most of the past week in the rain, cleaning equipment and prepping other sections of forest that would see fire only after the students returned home to Missoula.

The practicum is Seielstad’s brainchild, a mini-course he and his colleague Lloyd Queen had introduced at Montana in 2008. They had partnered with the Nature Conservancy in Georgia in part because the landscape there could benefit from fires every year and because the humid climate and fast-growing fuel beds made a forgiving setting for students learning to play with fire.

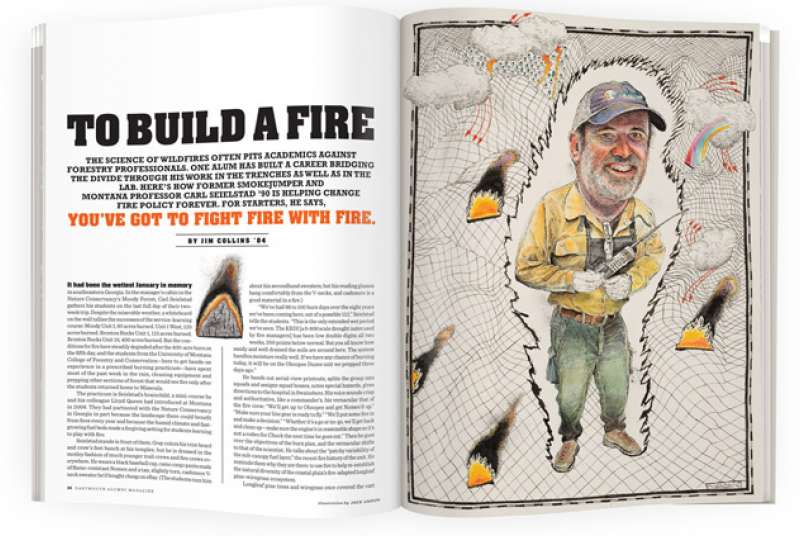

Seielstad stands in front of them. Gray colors his trim beard and crow’s feet bunch at his temples, but he is dressed in the motley fashion of much younger trail crews and fire crews everywhere. He wears a black baseball cap, camo cargo pants made of flame-resistant Nomex and a tan, slightly torn, cashmere V-neck sweater he’d bought cheap on eBay. (The students razz him about his secondhand sweaters, but his reading glasses hang comfortably from the V-necks, and cashmere is a good material in a fire.)

“We’ve had 96 to 100 burn days over the eight years we’ve been coming here, out of a possible 112,” Seielstad tells the students. “This is the only extended wet period we’ve seen. The KBDI [a 0-800 scale drought index used by fire managers] has been low double digits all two weeks, 200 points below normal. But you all know how sandy and well drained the soils are around here. The system handles moisture really well. If we have any chance of burning today, it will be on the Ohoopee Dunes unit we prepped three days ago.”

Seielstad made close to 200 jumps as a smokejumper in Idaho, testing himself against three of the fundamental elements—earth, wind and fire—on their terms.

He hands out aerial-view printouts, splits the group into squads and assigns squad bosses, notes special hazards, gives directions to the hospital in Swainsboro. His voice sounds crisp and authoritative, like a commander’s, his vernacular that of the fire crew: “We’ll get up to Ohoopee and get Nomex’d up.” “Make sure your line gear is ready to fly.” “We’ll put some fire in and make a decision.” “Whether it’s a go or no-go, we’ll get back and clean up—make sure the engine’s in reasonable shape so it’s not a rodeo for Chuck the next time he goes out.” Then he goes over the objectives of the burn plan, and the vernacular shifts to that of the scientist. He talks about the “patchy variability of the sub-canopy fuel layer,” the recent fire history of the unit. He reminds them why they are there: to use fire to help re-establish the natural diversity of the coastal plain’s fire-adapted longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem.

Longleaf pine trees and wiregrass once covered the vast savannas of the southeastern United States. The two evolved in tandem to create one of the most diverse plant communities on the planet—more than 50 species to the square meter in some places, many of them found here and nowhere else. The park-like landscape was marked by an open canopy of widely spaced trees and a rich understory of grasses and herbs. In 1539, when De Soto explored the Gulf Coast interior as far north as present-day North Carolina, he rode horseback through longleaf pine forests for days on end without having to dismount. John Muir wrote in 1867 that he “sauntered in delightful freedom” along sunny carpets of grasses and foot-long pine needles between the wide-set pines. Along with the native wiregrass, those “flashy” fuels supported frequent, fast-moving, low-intensity fires that reduced the woody vegetation and kept growing space open for wiregrass and new longleaf seedlings. Lightning struck fire into the resilient forests nearly every year, some years more than once. After decades of industrial logging, agricultural clearing, development and fire suppression, though, an estimated 97 percent of the pre-settlement longleaf pine-wiregrass forests had been lost.

On the 45-mile drive between Moody and the Ohoopee Dunes, Seielstad and his students pass orderly stands of yellow pine plantations, endless fields planted in cotton or Vidalia onions and dense, scrubby oak and slash pine forests.

Seielstad accepts the human development as inevitable. Where land could be given time to recover to a more natural state, though, he sees fire, in a good manager’s hands, as a powerful natural tool. That is a big part of his agenda.

By the time he stopped jumping fires in 2003, Seielstad had, as Norman Maclean ’24 wrote in Young Men and Fire, settled some things with the universe and with himself before turning to the business of the world. He had fought big Western wildfire on the ground with an elite crew of firefighters known as “hotshots.” He had made close to 200 jumps from the smokejumper base in McCall, Idaho, testing himself against three of the fundamental elements—earth, wind and fire—on their terms, in rugged and heartbreakingly beautiful wilderness areas across North America.

For most hotshots and smokejumpers, fire is a rite of passage. College students and young graduates backboned the ranks of Western fire crews going all the way back to the early 1900s, when Gifford Pinchot filled his nascent U.S. Forest Service ranger corps with Ivy Leaguers from the Yale School of Forestry. In Montana it has long been a part of the culture for young men to turn 18, fight fire and then grow up. In the classes Seielstad teaches at the university in Missoula and in the crews he brings to Georgia each January he sees young men and women who have chased “fire and ice”—worked on Forest Service crews in the summer and ski bummed in the winter—before getting on with their formal educations. Seielstad understands the appeal. “If Dartmouth were located in Montana,” he says, “the skiing part would still be there, but fire would be front and center in the outdoor culture.”

He came to fire by chance. He grew up in the dry Sierra town of Bishop, California, where his father, astrophysicist George Seielstad ’59, found the quiet radio space he needed for his research. Carl spent summers on his grandparents’ ranch in Cascade, Idaho, hearing tales of loggers and fire crews and stories of smokejumping from his two uncles. But it was a brown-bag lunch presentation at Dartmouth, given by a geology grad student in the basement of Fairchild Hall, that lit the spark. Seielstad remembers watching the wildfire slide show thinking, “Now that is cool.” He headed West right after graduation.

He hooked on with an engine crew that first summer in the Lowman Ranger District in Idaho, near the South Fork of the Payette River, not far from his grandparents’ ranch in Cascade. He was put up in a trailer that housed the fire camp’s 21 refrigerators, all of them filled with beer and constantly humming and throwing off heat that made the place feel like a low-level sauna all summer. His first time out Seielstad stopped 75 yards short of a stand of sub-alpine firs crowning with fire, flames torching up through the canopy a hundred feet above the ground. His foreman said, “Get out there.” Seielstad said, “What do you mean, ‘Get out there?’ ” He handled a chainsaw and a pulaski and found a physical outlet for his work ethic, which happened to be prodigious. He learned how to drive a split-axle truck and thread a maze of unmapped Forest Service roads and find water under the pressure of time and, most of all, to deliver when a crew was counting on him.

When the Lowman engine crew shut down that September, Seielstad slid over and filled an opening on the hotshot crew in Boise. A couple of weeks later, after mopping up a difficult fire at 12,000 feet in Colorado’s White River National Forest, Seielstad got airlifted out by helicopter. As the vast landscape stretched out below him, he welled up with gratitude for being able to experience such beauty so close. It was a feeling that would come back to him regularly during the next dozen summers and animate his view of the world.

“Carl is not smart: He’s scary smart. He’s a preeminent scientist, and his ability to anticipate an investment paying back in the long term is bold in the extreme.”

During three seasons with the Boise hotshots he learned how to navigate a hierarchical, competitive world filled with cocky college kids and “crazy vets and out-of-work hard-rock miners.” The job demanded and rewarded fitness, competence, accountability. The work itself—cutting fire lines, clearing brush, packing gear—was grueling and often no more glamorous than ditch digging. But it was ditch digging in spectacular and difficult locations, often on little or no sleep, with fire and the specter of death always nearby. Seielstad salted away his pay each summer, wages plus several hundred hours of overtime, and each fall wrote out a check for $12,000 or $15,000 or $20,000, eventually paying off all his college loans with fire.

After a few seasons it was clear that fire was not something he was going to pass through on the way to another life. Rather, his work with the hotshots tempered him for a deeper line of fire. He spent 11 seasons as a smokejumper, dropping out of de Havilland Twin Otter aircraft onto fires from Alaska to the Olympic Peninsula to the desert Southwest. He became a rookie trainer, then a spotter, responsible for making critical decisions in the air about when and where to drop men on fire. He gained the experience and the training to become a Type 3 incident commander (ICT3), one of the handful among the 11,500 people in the National Wildland Firefighter Workforce qualified to build a team and take charge of the logistically challenging mid-sized fires that threatened to blow up into full-on conflagrations, when the full-time pros would be brought in.

Although some smokejumpers held on deep into middle age, Seielstad knew that the grinding seasonal work was essentially a young man’s game. The year he made his last jump he was 35. He had a mortgage and a wife and a growing family at home. But he still had fire in him.

That same year, 2003, he earned a Ph.D. in forestry to go along with his master’s in geography. He had begun to understand things about fire behavior and ecology that ran counter to his training with the U.S. Forest Service. He had also discovered the deep chasm of mistrust between the academic world of fire scientists and the professional world of fire managers. He intended to build a career on both sides of the divide, believing he could build a bridge between them. He set out to do something that was arguably harder than fighting fire. He wanted to help change the way fire was fought.

When the United States created a national forest service around the turn of the 20th century, policymakers and scientists and the general public hotly debated the proper approach to fighting wildfires. Following the Great Fire of 1910, which scorched more than 3 million acres across Idaho, Washington and Montana in a flash of 48 hours, public opinion and the federal government welded together in a suppress-at-all-cost fire policy. The absolutist paradigm centered on the priority of saving economically valuable timber. One of the unintended consequences of the policy was a boom in industrial logging on federal lands, which timber companies justified by the logic that standing timber needed to be salvaged before it burned and became unusable. Federal policy, positioning fire as the enemy, became entrenched. It wasn’t until the late 1960s that the paradigm shifted, and fire policies gradually evolved to acknowledge what the science community had long argued: Wildfire is a natural, necessary component to maintaining healthy ecosystems in areas where species had adapted to the presence of fire through millennia.

Fire managers were given increasing latitude to let certain fires burn unchecked. Protocols were created for prescribed burning. But decades of suppression had created unnatural, fuel-rich conditions on the forest floors, resulting in fires that burned hotter and faster than nature had intended, with catastrophic results. In 1988 much of Yellowstone National Park burned. The 1994 South Canyon Fire in Colorado killed two of Seielstad’s crewmembers and 12 other firefighters, leading to public outrage and intense debate within the fire community. Through the 1990s and into the new century fire seasons grew longer, more destructive and more expensive. Climate models predicted that the trends would accelerate. Old-guard voices within the fire bureaucracy called for a return to the suppress-at-all-cost approach.

While the rules of engagement were changing, advances in science were leading to both deeper understanding and more sophisticated tools for management. In his academic work, Seielstad had irons in both fires.

His Ph.D., from the University of Montana, focused on the makeup of the shrubs, grasses and brushy trees that grew up from the forest floor and gave fuel to fire below the forest canopy. Using innovative ground-based and airborne laser altimetry to map surface fuels in 3-D, Seielstad created models that were far more detailed over large areas than previous methods based on small samples and extrapolation. His data fed into fluid-dynamic computer models that were revolutionizing the way scientists understood how fire moved. During the next decade he became an internationally recognized expert on fuels mapping, while expanding his research into weather-related phenomena that, he felt, represented the underdeveloped half of an emerging comprehensive fluid-dynamics system model. As he managed more and more big, Type 3 fires, he became acutely aware that fire behavior was linked not only to the topography and fuels it burned through, but also to the unseen changes in the atmosphere, small decreases in relative humidity, subtle shifts in wind speed and direction. “In essence,” he says, “we have the fluid dynamics of fire interacting with the fluid dynamics of the atmosphere. Both systems are incredibly complex. In fire science right now bringing those two systems together into a single model is the Holy Grail.”

By 2004 Seielstad had found a home in the FireCenter in Missoula, a small, interdisciplinary science, research and development cluster attached to the university’s College of Forestry and Conservation, where he also taught undergraduate and graduate students. The center was unlike any other in academia: a practical-minded, outcome-driven research and training hub whose mission was to apply science to fire management as quickly and broadly as possible. Nearly every staff and faculty member held a “red card,” putting them into the Forest Service system of national assets that could be called on to fight wildfire if needed.

At the FireCenter, in addition to his primary research and managing the Fire and Fuels Program, Seielstad worked to improve tools for gathering and delivering real-time fire intelligence to fire managers and crews on the ground. He used his technical expertise with remote sensing and geographic information systems to help design a smartphone application that could show managers how fire would react to constantly changing weather inputs. Remembering his frustration as an ICT3 trying to locate the freshest, closest available smokejumping crew, he developed a continually updated, web-based, master smokejumper database that compiled the qualifications of jumpers and dates of their last jumps and last days off.

The two thrusts of his research worked together. He was gathering and synthesizing data that made fire modeling more accurate. And he was creating tools that would put better decision-making data into the hands of fire managers. He knew that the Forest Service’s aggressive initial-attack approach quickly and effectively contained 90 to 92 percent of all wildfires, while nearly a third of the nation’s firefighting budget was consumed by the 8 percent of fires that ran out of control. These were fires that—despite massive manpower, air-dropped chemical retardant, and destructive heavy-construction road building and fire breaks—essentially continued burning until the weather changed. The cost of fighting a single big fire could run through more than $100 million of taxpayers’ money. Seielstad reasoned that if fire managers could more accurately predict how their fires would move, they could use their resources where they most counted and stop burning money. More effective use of resources could open up more funding for prescribed burning programs in areas where fuel beds were growing unnaturally dangerous. In time such approaches would reduce the areas where wildfires became catastrophic.

Seielstad limited his research and teaching to the standard academic year. In summer he kept his feet in fire, taking command of two or three big fires each season, usually close to Missoula in the northern Rocky Mountain West. Few people attempted to tightrope at such a high level in the two opposing realms. His director at the FireCenter, Lloyd Queen, likes to say that Seielstad embraced the tension. “Carl is not smart: He’s scary smart,” Queen says. “He’s a preeminent scientist whose willingness to assess risk and control his own destiny is absolutely unique. His ability to anticipate an investment paying back in the long term is bold in the extreme.”

But Seielstad’s insistence on working in both worlds came at a cost professionally. In recent years he worried about his looming tenure decision at the university. He worried that his academic affiliation compromised his influence in the world of fire. He had seen some gradual movement in fire policy and protocols, but he knew how much faster the change needed to happen. He began to doubt that he’d made the right choice.

The academic community regarded the semi-professional FireCenter warily. Scientists routinely dismissed fire managers as uneducated, resistant to new ideas, prone to making decisions that were inefficient or poorly thought out. The fire community, filled with career managers who equated experience and training with education, pictured academics sitting in front of their computers, concerned about Google Scholar citations and peer-reviewed publications, making theoretical decisions based on ideal models, clueless about the hard job of assessing conditions and balancing decisions in real time. Tom Zimmerman, a recently retired fire operations manager who admires Seielstad, articulates the mistrust: “Fire managers say that academics tell us exactly what we should have done, after the fact. They have high standards for precision in data and analysis and the luxury of a long time frame. But for a fire manager working a big fire, 50-percent precision might be the best information he can act on right now—which is better than 100-percent precision three days from now.”

Seielstad saw clearly both sides of the chasm. What he couldn’t see clearly was how much difference, if any, he was making. It was a feeling, no doubt, shared by anyone who attempted to change entire worlds where change came slowly and was hard to measure.

In the winter of 2014 he got a glimpse that he had made the right choice, after all: He became the first academic to win the Paul Gleason Lead by Example Award—perhaps the fire industry’s highest honor. The award recognizes individuals who have shown great leadership and vision in the field of fire management. Zimmerman presented the award at the university in Missoula in front of a crowd of people who had gathered to honor Seielstad’s achievement: colleagues from the FireCenter, current and former students, former crew mates, the dean of the College of Forestry and Conservation, old fire people, new fire people. Zimmerman read from the citation, which highlighted Seielstad’s “...unique opportunity to influence students of fire—both line-going and academic.”

One of Seielstad’s graduate students, Tyson Atkinson, helped draft the nomination. Atkinson argued that most university faculty and administrators didn’t understand the dilemma of school versus firefighting. “Carl has made that tension the essence of his efforts at UM,” Atkinson wrote. “Carl’s unique ability to cross boundaries has had major impacts on the careers of those who have worked with him.”

“This is not an honorary award,” Seielstad said. “I don’t know that anyone in academia recognizes it. But everyone in fire recognizes it. It means more to me than any other award I could possibly receive.”

Nearly a year later, on a brightening day in southeastern Georgia, Seielstad assembles his eight undergrads and one grad student near the corner point designated as Alpha on the Ohoopee Dunes burn plan. Malcolm Hodges, the Nature Conservancy’s director of stewardship in Georgia, is there. Anders Granström, a visiting fire sciences professor from Sweden, is there. Seielstad is educating the next generation of leaders who will drive fire research and fire policy—directly influencing the smaller bridges that will someday connect and strengthen the two worlds he straddles.

He speaks to them about longleaf pine and the pyric, fire-created Ohoopee Dunes ecosystem, the ground layer of turkey oak leaf litter and wiregrass and patchy mineral soil. He goes over the ignition pattern, has the squad bosses check their radios and make sure the drip torches are in order. “In the West,” he tells them, “if you screw up a fuel bed on a prescribed burn, you’ve lost that chance for a lot of years. It’s more forgiving here, but still: You need to know when to decide not to burn as well as how to burn.”

And with that, they Nomex up and throw some fire into the unit. The wiregrass, even covered by damp oak leaves, has adapted through millennia for just this moment. It crackles and jumps to life, spreading a low-intensity fire along the ignition line and licking toward the interior of the unit, barely darkening the fire-adapted trunks of the longleaf pines. A couple of the students whoop.

“Looks like a go,” says Seielstad.

Jim Collins is a freelance writer in Seattle and New Hampshire. His book about the Cape Cod Baseball League, The Last Best League, was published last year in a 10th-anniversary edition.