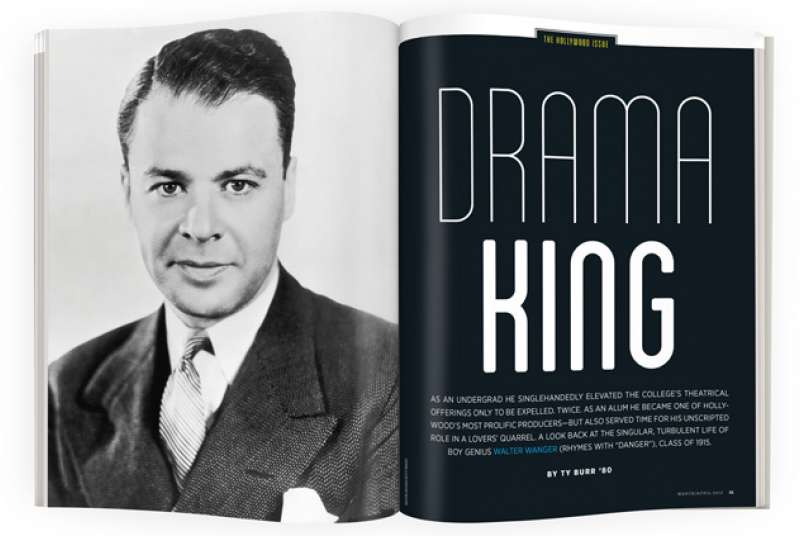

Drama King

If any Dartmouth alumnus deserves a statue in Hanover, it’s Walter Wanger. But where on campus should it be?

It could be positioned outside the film studies department’s offices to honor the Hollywood producer’s four-decade involvement with everything from The Sheik (1921) to Stagecoach (1939) to Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) to Cleopatra (1963).

Then again, it might be more fitting in front of the Hopkins Center to acknowledge his role in creating modern dramatics at Dartmouth as an undergraduate.

Would it be better still in front of Robinson Hall? Its 350-seat auditorium—the College’s first dedicated theater space (no longer there)—wouldn’t have existed had Wanger, as a sophomore, not personally persuaded donor Wallace F. Robinson, a Vermont business executive, to change the blueprints in 1912.

What about Silsby Hall, home of the government department and its international relations courses, to honor Wanger’s second career as a celebrated speaker on current events and global culture from the 1930s onward?

Or in front of Rauner library, home of the massive Irving G. Thalberg screenplay collection donated by Wanger?

By the old ski jump site, to commemorate Wanger’s production of that legendary, beloved 1939 cinematic stinker, Winter Carnival?

Or maybe it should just be outside the town jail on Lyme Road to mark the silver-haired producer’s four-month stay in prison in 1952 after he shot his wife’s lover in the testicles.

Wanger’s was, by any measure, a singular life.

Wanger is remembered today mostly by those who comb the credits of old movies, but in the late 1930s and early 1940s he was a national celebrity and one of the most highly paid men in Hollywood. An independent producer, allied to various studios but beholden to none, he was a maverick in the same league as David O. Selznick and Samuel Goldwyn, only with far more panache. Indeed, Wanger, born Walter Feuchtwanger, was the class act in an industry of hustlers, an urbane, articulate gentleman with impeccable grooming and high-minded civic ideals. And his Dartmouth education was a critical part of his public persona as an Ivy League movie mogul. Wanger was for decades the sole member of the species, and he used the distinction to stand out amid the hectoring Hollywood crowd.

Rare was the media profile that failed to mention Wanger’s Hanover connection, usually in tones of awe. True, film critic Otis Ferguson once wrote that Wanger “promoted an A.B. degree into one of the fanciest shell games even this industry has seen.” Yes, the producer was once spotted reading True Detective magazine behind a copy of Foreign Affairs. But to anyone looking for proof that there was intellectual life in the upper reaches of the movie business, Wanger was it.

All in all, not bad for a man who flunked out of Dartmouth—twice. Wanger’s college career was as artistically brilliant as it was academically a bust. He arrived on campus in the fall of 1911, cosmopolitan and ready to change the world, or at least Hanover. The scion of thoroughly assimilated German-Jewish immigrants from San Francisco—Wanger’s father had made a fortune in denim before dying when his son was 11—young Walter had traveled to New York and Europe, seen Sarah Bernhardt on the stage and was well versed in fine art and literature. The family expected him to go into banking. He had other ideas, most of them having to do with the daring and sophisticated stage presentations unfolding in his head.

By contrast, theater at Dartmouth was the same as at other major educational institutions at the dawn of the 20th century: an excuse for college men to dress up like girls. Wanger spent his freshman year ignoring his studies while trying to convince school administrators to let him mount the latest dramas from Broadway and London. His academic transcript, now in the files of Rauner, is a sorry thing. By late winter of his first year at Dartmouth, Wanger was “separated” from the College—what they called expulsion back then—and immediately sailed with wealthy relatives to Europe, where he plunged into a study of the New Stagecraft movement, the set designs of Edward Gordon Craig and the latest developments in playwriting.

A drama professor at the University of Heidelberg was so impressed by the polished young American attending his lectures that he recommended Dartmouth take him back. Wanger returned in the fall of 1912 and immediately got down to business.

He was appointed assistant manager of the Dramatic Club, then manager. He secured the rights to a daring New York hit, The Rising of the Moon, and convinced the junior prom committee to stage it. He found plays or wrote them under a pseudonym and staged musical-comedy revues with costumes imported from Paris and sets built and shipped up from Boston. Wanger created Dartmouth’s first set-design department and took over the rehearsal and directing duties previously done by professional directors hired by the College. He put on a new drama every month, even during—horrors—football season. He did everything but study.

“I don’t think they had seen a student like that in any endeavor outside of athletics. He basically took the place over, and it was ripe for taking,” says Matthew Bernstein, a film professor at Emory University and author of the 1994 biography Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent.

The climax to Wanger’s glittering Dartmouth career came in the winter of his junior year, when he secured rights to the comedy The Misleading Lady, written by playwright Charles Goddard, class of 1902, and staged it in Hanover simultaneously with the play’s New York run. To top the triumph, the Dartmouth players were invited to Manhattan to stage their version in a starry two-night stay at the Fulton Theater.

A February 1914 article in the New York World, titled “How a New York Freshie at Dartmouth College Succeeded in Putting Hanover, N.H., on the Theatrical Map,” stated that, “Young Wanger has been the whole thing in Dartmouth dramatics….The faculty of Dartmouth stand for all this with an equanimity that is certainly a testimonial to the boy manager’s genius.”

In fact, the faculty of Dartmouth were astonished by the whirlwind in their midst. Professors occasionally outnumbered students at Wanger productions, and when a few of the latter left one play early, they were chided in the pages of The Dartmouth by an irate English professor. Charming and erudite, Wanger coasted atop his lack of interest in academic achievement until the College could no longer ignore his failing grades. Despite an official academic warning in November 1913, the boy genius had a Christmas show planned for the grand opening of Robinson Hall in his senior winter—Wanger had even found dwarves to play the elves—but it was canceled when he was expelled for the second and final time.

The campus magazine The Bema lamented his departure: “Two years ago the college dramatics were on the same scale as those of the ordinary preparatory school….Yes, there was talent, indeed, but the college conservatism and lethargy could only be broken by a dominant, enthusiastic, capable personality. Such a personality came in the person of Walter Wanger, a practical dreamer, a fanatic with common sense.”

By the time the article ran Wanger was already in Manhattan, working as an assistant to the eminent stage producer Granville Barker. The press had covered his exit from undergraduate life: “Wanger So Good with Dartmouth That Granville Barker Hires Him” was one headline.

All this was prelude to the main drama of Wanger’s life. He discovered movies during WW I—although he signed up as an Army Signal Corps pilot, Wanger apparently crashed more planes than he flew—and his involvement with Allied film propaganda was critical to the future producer’s idealistic vision of cinema as a tool of social uplift and influence. Back home, the confident young man was hired to run the New York offices of Famous Players Lasky, the studio that soon would become Paramount Pictures. From there Wanger embarked on a wayward, high-profile career that saw him bounce from Paramount to Columbia to MGM before setting up shop as an independent producer. During the next quarter century he had distribution agreements and offices at most of the major studios, but functioned—at least on paper—as his own man, making his own movies.

He had a fine run as these things go. Films produced under Wanger’s watch include such acknowledged classics as John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939)—the film that made a star of John Wayne—Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent (1940), the Greta Garbo period drama Queen Christina (1933), Frank Capra’s The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933) and such fatalistic Fritz Lang gems as You Only Live Once (1937) and the proto-noir Scarlet Street (1945). Dig a little deeper and you hit the aching Max Ophuls melodrama The Reckless Moment (1949), the slightly demented romance History Is Made At Night (1937) and the extremely demented Washington, D.C., political fantasy Gabriel Over the White House (1933), which casts Walter Huston as a heroic fascist president.

During his career Wanger signed the Marx Brothers, Maurice Chevalier, Claudette Colbert and Susan Hayward. He gave speeches about the edifying potential of the movies. He crossed swords with censors and fashioned a public image as a bespoke industry rebel—an outsider on the inside. “Wanger really used the producer as a cult of personality,” says Bernstein. “Selznick, Goldwyn, Mayer—everybody had their publicist, but he just really made his personality a crucial part of what he was doing. And I think that trend started for him at Dartmouth.”

It came home to Dartmouth as well. Wanger made more than his share of uninspired programs and outright hokum, but Winter Carnival has a special niche in both the cinema’s and the College’s halls of infamy. The rumor persists that the production was Wanger’s last-ditch attempt to woo an honorary degree out of Dartmouth, but in fact the board of trustees had taken the unusual step of awarding him an A.B. in June of 1934. Still, when Wanger appeared on campus at the start of 1939 Winter Carnival, it was part of a full-scale charm offensive that included the film’s co-screenwriters, novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald and Budd Schulberg ’36, a Hollywood studio brat.

The visit proved to be a legendary fiasco, with Fitzgerald falling off the wagon, down the steps of the Hanover Inn and out of the production. (Wanger fired him and replaced him with Schulberg’s fellow alum and future Dartmouth film professor Maurice Rapf ’35—who cut short his honeymoon to return to Hanover.) The movie turned out to be collegiate tripe, named one of the worst of the year by Time magazine and considered an instant camp classic by generations of incoming Dartmouth freshmen. Schulberg, at least, got a book out of it, the best-selling 1950 roman à clef The Disenchanted, which features a smoothly soulless studio executive with Wanger’s taste in haberdashery and the name of Victor Milgrim.

That said, the WW II era was Wanger’s professional peak, with a strong slate of movies, the presidencies of both the Dartmouth Alumni Association and the Motion Picture Academy and a public profile that saw the producer giving speeches urging America to enter the war while using media to spread democratic ideals abroad. “He was utterly a creature of the system,” says Bernstein. “But at the same time he promoted himself as being different from the suits, as being a freethinker. And when he couldn’t do it in his films, he would do it in his speeches.”

“I don’t think he flaunted it,” says Wanger’s younger daughter, Shelley, an editor at Random House in New York, about the Ivy League connection and any industry cachet that came with it. “But I know he was perceived as intellectual, and I think that somehow became his reputation. He certainly did get a lot of his ideas from books. And I’m sure maybe even discussing things he’d read. If he’d read a Camus book—I can’t see [Fox head Darryl] Zanuck thinking that was interesting.”

Wanger’s winning streak lasted until the postwar years. In 1948 he gambled and did something an independent producer should never do: He put all of his financial eggs into the basket of one movie, Joan of Arc. By the time it came out that year, star Ingrid Bergman was in the throes of a scandal over her adulterous relationship with director Roberto Rossellini, and absolutely no one wanted to see her play the Maid of Orleans. Wanger lost his shirt.

Worse, he lost his freedom after temporarily losing his sanity—that was his defense, anyway—and shooting Jennings Lang on December 13, 1951, in the parking lot of the MCA talent agency. Lang was agent to the producer’s second wife, actress Joan Bennett. Wanger’s suspicion that they were also lovers had prompted him to hire a private eye. Lang survived, the case grabbed headlines for months and Wanger ultimately served four months at the Castaic Honor Farm two hours’ drive north of Los Angeles. At one point after the shooting he buttonholed a friend and begged for information: “No one will tell me. Did I hit what I was aiming at?”

Ironically, the brief incarceration gave Wanger’s career a late-inning boost. Even a minimum security facility was an eye opener for the elegant producer, fuelling both his progressive ideals and creative juices and leading to two of the better prison films in Hollywood history, 1954’s Riot in Cell Block 11 and 1958’s I Want to Live!, which won Susan Hayward a best actress Oscar. In between was 1956’s paranoid classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers, a film that summed up Wanger’s dark new take on the American way.

It looked as though he was back in business. Then came Cleopatra, a film that started production in 1959 as the logical culmination of a fascination with exotic romances dating back to the torrid stage productions of Wanger’s youth.

By the time it came out in 1963 the budget had ballooned out of control, bankers had taken over Twentieth Century Fox, leading lady Elizabeth Taylor had left her husband for leading man Richard Burton and Wanger had been fired from his own movie.

He retaliated by publishing his production diary as My Life with Cleopatra in 1963. The book was a hit—the last Wanger would have. He never got another movie made and died of a heart attack (his third) in 1968, at the age of 74. This magazine omitted the Lang affair from his obituary.

Are there morals to Wanger’s life? Perhaps. Follow your talent, even if it gets you kicked out of college. Differentiate yourself. Turn lemons into lemonade—or prison sentences into prison films, as you will. Never trust an alcoholic writer. Aim high. Shoot low.

All valuable life lessons, but not least is the sense that, in the end, Wanger’s greatest production was himself. That started at Dartmouth, and the arts in Hanover—theater in particular—owe a large and too rarely acknowledged debt to a freshman who showed up on campus a little more than a century ago, consumed with ambition. Despite what his transcript tells us, Walter Wanger made the grade.

Ty Barr, film critic for the Boston Globe, is a regular contributor to DAM. He lives in Newton, Massachusetts.