Voices in the Wilderness

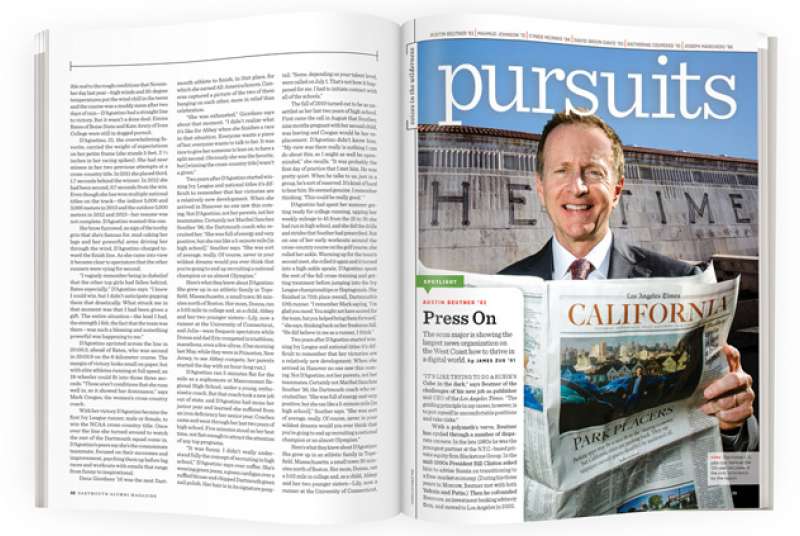

Austin Beutner ’82

Press On

The econ major is showing the largest news organization on the West Coast how to thrive in a digital world.

“It’s like trying to do a Rubik’s Cube in the dark,” says Beutner of the challenges of his new job as publisher and CEO of the Los Angeles Times. “The guiding principle in my career, however, is to put myself in uncomfortable positions and take risks.”

With a polymath’s verve, Beutner has cycled through a number of disparate careers: In the late 1980s he was the youngest partner at the N.Y.C.-based private equity firm Blackstone Group. In the mid-1990s President Bill Clinton asked him to advise Russia on transitioning to a free-market economy. (During his three years in Moscow, Beutner met with both Yeltsin and Putin.) Then he cofounded Evercore, an investment banking advisory firm, and moved to Los Angeles in 2000.

In 2007 Beutner was mountain biking near his house with friend Jake Winebaum ’81. Coming down a hill, Beutner flew off his bike and suffered a concussion and a broken neck, requiring him to be airlifted to the hospital. During the months of recovery, he spent more time with his wife and four kids. “While lying on my back recuperating I decided I wanted to make a difference through my daily efforts, not just through philanthropy. The accident allowed me to go beyond service at the policy level.”

Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa appointed him deputy mayor in charge of economic development—or “jobs czar”—overseeing a dozen city departments, including the L.A. Department of Water and Power, the nation’s largest municipal utility. Beutner even briefly considered a run for mayor of Los Angeles.

His current focus is the Times. After he made an unsuccessful bid to buy the paper, which was on the block as owner Tribune Co. struggled to emerge from bankruptcy in 2012, Beutner was approached by Tribune to become publisher instead. “My initial reaction was, ‘No, thanks’—I hadn’t had a boss in 20 years,” he says. “But then I thought this would be fantastic for our civic life if we could find a way for the L.A. Times to survive.”

He took on the job in August 2014 and already has made some major changes: student journalists are covering 41 high schools on a new L.A. Times website, a weekly e-newsletter is about to go daily, digital tools are now in every reporter’s pocket and the iconic “California” section, cut in 2009, is back. “We have 500 journalists on staff,” he says. “The L.A. Times is the largest news organization west of the Hudson. We have an enormous audience. We have 4 million readers on Sundays. This is also an engaged audience—90 percent of our subscribers voted in the 2012 general election. One interesting dynamic in the digital age is that our readers come to us through search and through social. It is word-of-mouth, these little neighborhoods like in the past, only now they are digital.”

The L.A. Times has one of the few test kitchens left at any newspaper in the country, and in this new digital environment Beutner believes the paper can leverage the current fascination with food into real advertising dollars. The same goes for other niche coverage areas—such as the state of California, the Pacific Rim and the entertainment industry—where the paper holds a natural edge.

Facing challenges seems to be a hard-wired norm for Beutner. Since his accident he has continued to exercise daily at dawn: He runs, surfs, and paddleboards. He even rides his mountain bike down the same trail where he crashed. —James Zug

Mahmud Johnson ’13

Making Every Kernel Count

At 23, Johnson is no stranger to running a business. Propelled by a $150,000 40 Chances fellowship, awarded by the Howard G. Buffet Foundation, he has most recently founded Kernels for Peace (K4P), Liberia’s first fair trade palm kernel oil processing factory. K4P bridges a gap between an estimated $4 million of wasted palm kernels and a high demand for palm oil in the soap industry. “This initiative is representative of big picture development challenges in Liberia, where there are incredible resources and potential not being tapped,” Johnson says. “We can be our own employers and create value in the economy.”

K4P has earned Johnson recognition as the Business Startup Center’s 2014 Entrepreneur of the Year and has increased thousands of small farmers’ incomes by 25 to 35 percent. The organization creates jobs in areas where unemployment is high and pledges to reinvest 50 percent of profits into local communities after two years in operation.

Johnson’s former entrepreneurial ventures have included selling charcoal and T-shirts, and his unconventional path has taken him through a pre-Dartmouth position as public affairs intern for the president of Liberia, a job as co-host of a Liberian radio show and a drink with U2’s Bono (Johnson still has the Heineken bottle).

K4P takes his previous ventures to a new level. “The opportunity to help somebody earn a living is huge for me. It’s amazing to go to the factory site and see people working at something that was just an idea in my mind,” he says. “When people have better livelihoods, they have access to more choices and can choose paths that create better futures. I want to continue to use business to solve social problems in Liberia.” —Rianna P. Starheim ’14

Cynde McInnis ’94

In the Belly of a Beast

McInnis is not your everyday whale enthusiast. Beyond training dozens of interns and volunteers, and leading nearly 2,000 whale watches during her 20 years at Cape Ann Whale Watch in Gloucester, Massachusetts, she has embarked on a five-year study of ocean and whale health. She has also served as the American Cetacean Society’s education chair. Her most recent project—dubbed the “Whalemobile”—has given her obsession a whole new form.

With Nile, a 43-foot inflatable whale, as her tool, McInnis travels across Massachusetts teaching grade school students about whale anatomy and behavior. Complete with lungs, ribs, vertebrae and a stomach, Nile—modeled after a real humpback of the same name—has helped to augment limited marine education at local elementary schools. “They don’t have the money or funding” for trips anymore, she says, “so I thought the next best thing is to bring a giant inflatable whale into their school that the kids can go inside.” (McInnis gives many of her presentations within Nile’s large, hollow belly.) While in her early days at Cape Ann, McInnis was accustomed to taking as many as 100 school groups on watches in the spring. Today the number tops off at around 20.

Describing the mammals as her “hook” to get kids to think about protecting the environment, McInnis hopes that through her programming, students will acquire a similar interest in the world around them. “I feel like whales are that thing that can be really powerful to get the kids to care.” —Marley Marius ’17

David Brion Davis ’50

An Historian for the Ages

Davis is often called one of the greatest cultural historians in the world—and was recognized last summer with the National Humanities Medal “for reshaping our understanding of history,” said President Barack Obama at the ceremony. A leading authority on the history of slavery and abolitionism, Davis is widely recognized for his Problem of Slavery trilogy (the first book, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture, won the 1967 Pulitzer Prize; the second, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, won the 1975 National Book Award and the Bancroft Prize). The Sterling Professor of History Emeritus at Yale and founder of its Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition, Davis is respected as much for his more than 50 years of scholarly work as for the many distinguished scholars who call themselves his students. “When his latest book came out last winter the applause of fellow scholars was deafening,” says Yale historian John Demos. That book, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Emancipation, is “essential reading for anyone wishing to understand our complex and contradictory past,” said The New York Times.

Davis attended Dartmouth on the GI Bill (after service in the Army) and majored in philosophy before earning his Ph.D. in history from Harvard in 1956. His almost half-century study of slavery leaves him cautiously optimistic that equality is attainable, but it will take time. “Since the 1960s we’ve made great progress on many fronts with regard to race,” says Davis. “The Ferguson [Missouri] situation and the riots that developed right away indicate that we could have unexpected violence and conflict between whites and blacks. The depth of prejudice and racism has been extremely great and extremely difficult to overcome.” —Abigail Drachman-Jones ’03

Katherine Cespedes ’10

Miami Nice

A gap year working with under-resourced students in Miami before her senior year at Dartmouth set Cespedes on the path to philanthropy. Now, as project manager at the nonprofit Confucius Institute, she expands study abroad opportunities in higher education for underrepresented communities. “Philanthropy is about bringing like-minded people to a common purpose to achieve greater things than we could individually,” says the philosophy major. “I measure success in giving resources to communities that have not had access to opportunities before.” In a typical day Cespedes will connect Confucius students with job opportunities, tap contacts for new partnerships, manage budgets and advise students on course selections.

Although she cites the constant battle for funding as a downside of working for nonprofits, she’s never considered doing anything else. “This work is about creating for others the opportunities that were given to me,” says Cespedes, who attended middle and high school in Miami as a Peruvian international student. “I came to Miami to give back to the community that had given me so much during my college preparatory years.” Recognized as a 2014 “Miami Change Maker” by the Ashoka Foundation’s 30 Days of Change Initiative, she also serves on the steering committee of Philanthrofest, the state’s largest community engagement fair to connect volunteers, donors and organizations. “When people and organizations work in collaboration,” she says, “there’s the potential for great things.” —Rianna P. Starheim ’14

Joseph Marcheso ’96

Bravissimo!

“If the world of classical music consisted only of piano, I wouldn’t be a musician,” says Marcheso, music director and principal conductor of Opera San Jose and a staff conductor at the San Francisco Opera. Growing up in New York City, Marcheso took piano lessons, largely to please his parents. He was far more interested in the music he heard in Star Wars and James Bond films. At age 8 he saw his first opera—a dress rehearsal of Hansel and Gretel. A few years later, after watching Amadeus on television, he listened to all of Mozart’s operas. “By the end of high school I had reached the end of Verdi and the beginning of Wagner,” he says. “Once I understood what a conductor was—once I knew a conductor existed—I knew that’s what I wanted to be.”

Marcheso graduated from Dartmouth with a degree in music and spent the next eight years at the Amato Opera, a 100-seat community theater in Manhattan. He worked his way up to music director, overseeing six operas a year, each with a dozen performances. In 2005 he left to pursue his master’s at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Last July he took on his new role at Opera San Jose—where he “did a superb job with the orchestra” in the 2014-15 season opener, Rigoletto, according to opera critic Michael Vaughn.

For those who wonder about a conductor’s gyrations, Marcheso explains that most listeners don’t understand “the amount of premeditation that goes into what they’re experiencing,” he says. “When you see the fingers really going and the conductors really gesturing, it looks like people are just letting their instincts speak. But the amount of time spent dissecting and experimenting before it gets to that point to make those things seem that way—for a quality opera production, every aspect has been thought of and tested.” —Abigail Drachman-Jones ’03

Joseph’s top 4 operas

Verdi’s Don Carlo: “Majesty, brooding and austerity personified”

Wagner’s Parsifal: “Magical spiritual longing—and the transformation music is the most amazing stretch of music ever written.”

Adams’ Nixon in China: “I love minimalism, and this opera is startlingly original, human and fun.”

Britten’s Peter Grimes: “Dark story, beautiful, intricate music, heartbreaking text”