The sun has just started to rise over the St. Jude’s Shrine of the West in a hardscrabble neighborhood of downtown San Diego when Dinesh D’Souza pulls his nondescript rental car into the Catholic church’s small parking lot. Children in school uniforms and stray dogs amble past along palm-lined sidewalks.

As D’Souza emerges into the harsh morning light he is, to be kind, not looking his best. Unshaven and dressed in what appear to be clothes he has slept in, he is sporting a bad case of bed head. He is one month into an eight-month sentence that requires him to spend nights at a nearby federal correctional reentry facility, where he is avoiding the showers. D’Souza’s strict curfew requires him to be inside the gates before 7 each night, and he cannot leave until 7 a.m. the following day—except on Sundays, when he is confined there all day, one of 120 men. He sleeps on a thin mattress in a dormitory setting. He can clean himself up when he returns to his house most mornings, but on Mondays he must come directly from the facility to the church.

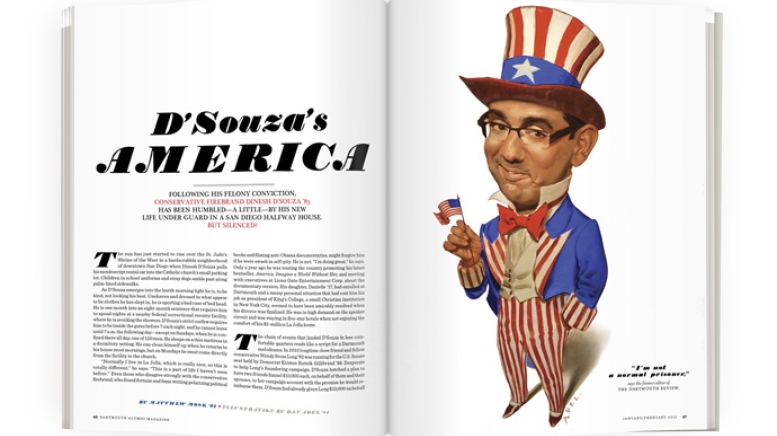

“Normally I live in La Jolla, which is really nice, so this is totally different,” he says. “This is a part of life I haven’t seen before.” Even those who disagree strongly with the conservative firebrand, who found fortune and fame writing polarizing political books and filming anti-Obama documentaries, might forgive him if he were awash in self-pity. He is not. “I’m doing great,” he says.Only a year ago he was touring the country promoting his latest bestseller, America: Imagine a World Without Her, and meeting with executives at Lions Gate Entertainment Corp. about the documentary version. His daughter, Danielle ’17, had enrolled at Dartmouth and a messy personal situation that had cost him his job as president of King’s College, a small Christian institution in New York City, seemed to have been amicably resolved when his divorce was finalized. He was in high demand on the speaker circuit and was staying in five-star hotels when not enjoying the comfort of his $3-million La Jolla home.

The chain of events that landed D’Souza in less comfortable quarters reads like a script for a Dartmouth melodrama: In 2010 longtime close friend and fellow conservative Wendy Stone Long ’82 was running for the U.S. Senate seat held by Democrat Kirsten Rutnik Gillibrand ’88. Desperate to help Long’s foundering campaign, D’Souza hatched a plan to have two friends funnel $10,000 each, on behalf of them and their spouses, to her campaign account with the promise he would reimburse them. D’Souza had already given Long $10,000 on behalf of himself and his wife—as much as he could legally donate—so by routing more money through so-called “straw donors” he committed a federal crime.

In response to charges brought against him in January 2014, D’Souza pleaded guilty in May on the day his trial was scheduled to start. At his sentencing hearing in September he explained that his motivation stemmed from the intense personal ties he has to those who befriended him upon his arrival in Hanover when, as a recent immigrant from India, living in a triple in Russell Sage, he was rootless. His closest friendships, including that with Long, were formed as a staffer for The Dartmouth Review, to which Long recruited him.

D’Souza not only still thinks he was singled out for prosecution, he continues to say so. “I believe if someone else had done this—not me—they would have handled the case differently.”

Several former staffers wrote letters of support for him to the court, including Laura Ingraham ’85, who recalled D’Souza being teased by his Dartmouth classmates because he had only one pair of shoes, “with huge holes in the soles!” She continued: “I didn’t care. Dinesh was teaching me how to write a news story, edit copy, track down sources and, most importantly, stay firm in my principles.” Long described how she and D’Souza bonded over a yearning “for truth and intellectual honesty” when they found each other in Hanover.

“That was my group,” D’Souza says. “We were super close. At that time the paper was broke. When you’re getting something off the ground, you spend endless hours together.” Long would later describe D’Souza as being “like a brother” to her.

When Long felt an itch to challenge Gillibrand for her Senate seat, D’Souza was one of the first people she called for advice.

“We sat down to discuss whether she should run,” D’Souza recalls. “I said, ‘I don’t think you should.’ Some people are very thick-skinned. I am. I don’t know if I was originally, but I have become that. ‘But,’ I said, ‘You’re not. And a campaign can break your wings.’ So I said, ‘Don’t do it. Because I think a campaign can crush you. But if you do, I will help you.’ ”

His friend’s long-shot campaign against the incumbent failed to gain traction. Yet, D’Souza told the court, Long would call him for help: Could he meet with some Indian doctors who might donate? Could he speak at a fundraiser in Westchester? At the time D’Souza was still running a college and had just released a movie. He was, he said, completely swamped.

“I can see and feel her struggling,” he testified. “I don’t think she’s going to win. Nobody does. But I can see that personally she is humiliated. Her campaign is kind of seen as a joke. I want to help her.”

Depending on who describes it, the criminal act that followed was either the product of brazen arrogance or overzealous generosity. Both Gillibrand, who won reelection on November 6, 2012, with more than 72 percent of the vote, and Long declined to comment to DAM on D’Souza’s sentence. D’Souza and his friends painted his effort to channel more money into Long’s campaign as an act of kindness gone awry. Christopher Baldwin ’89, a former Review editor who now works in finance in New York City, wrote an impassioned letter to the judge to defend D’Souza’s motives, calling the crime “a wrong rooted in friendship.” Even more importantly, D’Souza argued, his efforts were never intended to corrupt the political process. He had no intention of seeking favor for legislation or an advantage for a government contract. Only to see his friend elected.

Prosecutors, however, focused on D’Souza’s apparent efforts to cover his tracks, telling the people who made the donations to lie about the transactions and reimbursing them with wads of cash that could not easily be traced. “This is not a case where the defendant had a momentary lapse in judgment,” prosecutors wrote in their memo to the judge.

Part of what seemed to gall Judge Richard M. Berman when it came time for D’Souza to stand for his sentence was the defendant’s refusal, even after entering his guilty plea, to stop asserting that he had been the victim of a political witch-hunt. While awaiting his sentence D’Souza had defied his lawyer’s strong admonitions and gone on TV. He told Fox News’ Megyn Kelly: “You don’t want to have a country in which Lady Justice has one eye open and she winks at her friends and then gives the evil eye to her enemies.” The judge played a clip from another one of his guest appearances during the sentencing hearing.

“Notwithstanding Mr. D’Souza’s contention in his post-plea TV interview that you saw,” Berman said sternly, “I’m totally confident that Lady Justice is doing her job and that she’s not taking off her blindfold to target Dinesh D’Souza.

“Almost every defendant expresses remorse for his mistake,” Berman said. “They often mean it was a mistake in hindsight, and they are certainly sorry that they got caught. But Mr. D’Souza’s crime was clearly no mistake.” As Berman prepared to hand down the sentence, he continued, sounding almost exasperated, “I’m not sure, Mr. D’Souza, that you get it. It’s still hard for me to discern any personal acceptance of responsibility in this case.”

Benjamin Brafman, D’Souza’s seasoned criminal defense attorney, cringed when the judge spoke. “To be completely honest, most of the people in the room at the time, including me, thought that incarceration was a strong possibility given the tenor of the court’s opening comments,” he says.

What followed, to D’Souza’s great relief, was not a sentence of 10 to 16 months in federal prison, as federal guidelines permit, but Berman’s order that D’Souza spend eight months in a community confinement center. Further, Berman ordered D’Souza to spend an eight-hour day each week teaching English as a second language to immigrants, an exercise Berman said he hoped might bring some humility to a defendant the judge described as an “almost compulsive talker” and “not a listener.”

With the sun rising over St. Jude’s, D’Souza steps into the dingy church classroom where two dozen middle-aged Mexican women are arriving to learn English from a man considered by his legions of supporters to be one of the most mesmerizing practitioners of the language. It is the first of four classes that day in which he will serve as an aide to a high-energy instructor named Vicky Calero. D’Souza’s connections to the acting bishop of San Diego facilitated this placement quickly. Both Calero and D’Souza consider the arrangement, still early in its development, a budding success.

Calero develops lesson plans while D’Souza looks for creative ways to engage the students. On this morning Calero uses music to help coax shy students to speak in their new language. D’Souza hunts down a tune on his phone that he thinks might work well, then steps to the front of the class and begins to sing.

“Wise men say…only fools rush in,” he croons, doing his best Elvis Presley imitation. “For I can’t help…falling in love with you.”

In the afternoon the setting for his community service moves to the gated, manicured campus of Mater Dei Catholic High School in the suburb of Chula Vista. At the front of a spacious, well-lit classroom he cues up a video trailer of his America documentary on the digital smart board.

This is the first time D’Souza is assisting Calero with her afternoon class, and she is enthusiastic. “It’s really a privilege that he’s helping us,” she tells the class. As he greets the adult students taking their seats he starts by recounting his improbable life tale, placing a special emphasis on shared histories as newcomers to America. He was, he says, a high school exchange student from India who expected to remain in the United States for only one year. Instead, he stayed on to attend Dartmouth. He parlayed his education into a career writing bestsellers and making documentary films. His next goal, he tells them, is to create commercial feature films in the vein of Oliver Stone, but from a conservative perspective.

A student flips off the lights and D’Souza rolls the Hollywood trailer for America, which he narrates over the flourishes of dramatic music and reenacted scenes from the Revolutionary War. The students look entranced. As the lights come back up, many direct smiles at Calero, as if to say: This is a pretty unusual new teacher’s aide.

Then, before Calero steps back to the front to launch into her prepared lesson on verb tenses, D’Souza tells the class that one of his 13 books, What’s So Great About Christianity, has been translated into Spanish, “and if any of you would like to have a copy of that book, tell me and I will bring it in and give it to you the next time. Put your hands up. Who wants a copy?” Every hand goes up. D’Souza smiles broadly, promising to bring enough for everyone.

D’Souza says his next book may well chronicle his experience with the judicial system. He studies the culture and residents of his halfway house “like an anthropologist in New Guinea,” he says.

Unlike him, most of the residents have transitioned to the facility from a prison term. Some have committed violent offenses. Most are serving time for drug- or border-related crimes. When he arrived there in September, he says, he made it his goal to avoid direct contact or communication with his fellow inmates. “Don’t stare them down, don’t intimidate them. But neither should you look away or look down,” he says. “I’m just straightforward. My main conversations are, ‘Hello,’ ‘Thank you,’ ‘It’s over there.’ That’s all I say to people.”

Sometimes he lies in bed and listens to conversations. “As a writer, it’s fascinating,” he says. “Near our facility is a Del Taco. I just listened to four Hispanic guys last night for an hour discuss the breasts of the woman behind the counter in Del Taco, at great length. I was just lying there. They were right behind me and I was just listening.”

There is no question the sentence has taken a toll on D’Souza. But if Judge Berman thought he would slow the seemingly non-stop political monologue that fuels D’Souza’s empire, a look at D’Souza’s Twitter feed is enough to know that hasn’t happened.

D’Souza not only still thinks he was singled out for prosecution, he continues to say so. “I believe if someone else had done this—not me—they would have handled the case differently,” he says. He remains convinced the Obama administration views him as an enemy and has an active hand in his treatment, adding, “I’m not a normal prisoner.”

Nor is he slowing down. On weekdays when he’s not in a classroom he is hard at work recruiting investors for his next film project. And he is making headway at getting his books and documentaries accepted as part of the curriculum in the Texas public school system.

As focused as he is on the future, D’Souza becomes reflective when asked whether his experience with the justice system has humbled him.

“There has definitely been a strong element of that,” he says. “The true humbling, which is what the government sought, has not happened. There’s a guy who came over from the Taft federal prison who is now in the halfway house with me. He’s humbled in the sense that he’s crushed as a human being. He’ll never recover. That kind of humbling has not happened to me. I’ve never felt crushed.

“It may be I’ve had a charmed enough life that I began to think the rules don’t apply to me,” he says. “If that’s the case, this is a very good thing to show me that they do.”

Matthew Mosk is a regular contributor to DAM. A two-time Emmy winner, he is an investigative reporter for ABC News in Washington, D.C. He lives in Annapolis, Maryland.