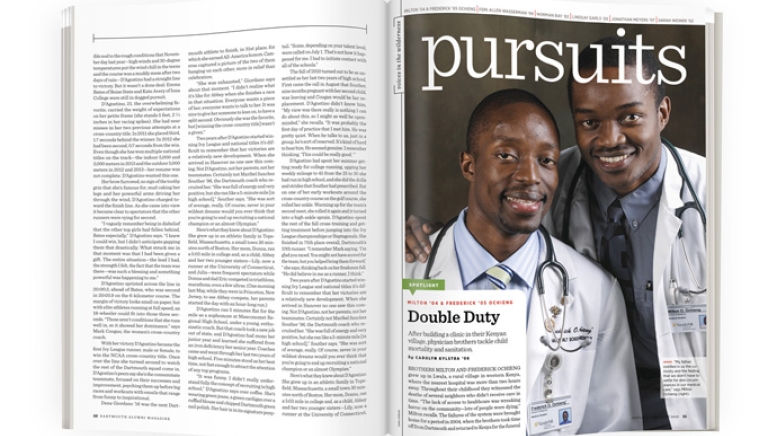

Milton ’04 & Frederick ’05 Ochieng

Double Duty

After building a clinic in their Kenyan village, physician brothers tackle child mortality and sanitation.

Brothers Milton and Frederick Ochieng grew up in Lwala, a rural village in western Kenya, where the nearest hospital was more than two hours away. Throughout their childhood they witnessed the deaths of several neighbors who didn’t receive care in time. “The lack of access to healthcare was wreaking havoc on the community—lots of people were dying,” Milton recalls. The failures of the system were brought home for a period in 2004, when the brothers took time off from Dartmouth and returned to Kenya for the funeral of their mother, who had died of HIV/AIDS. The following year their father also died from the disease. “Neither of them had access to antivirals,” Milton says. “It made me wonder if only we’d been a year or two earlier in our efforts, maybe they would have lived.” Those efforts culminated in the 2007 opening of the Erasmus Ochieng Memorial Lwala Community Health Center, named in memory of their father.

Milton was inspired to bring better healthcare to Lwala during his sophomore winter, when he went on a Tucker Foundation service trip to Nicaragua to help build a clinic for women and children. “If a group of college students could build a clinic in Nicaragua in one week, why not try the same thing in Lwala?” he says. Milton began planning logistics for the clinic, and Fred took charge of fundraising. With an initial goal of $25,000, the brothers reached out to a campus minister, who helped them secure $9,000. Upper Valley residents donated another $20,000. (The brothers have since raised $5.4 million.)

Their father, who taught high school chemistry in Lwala, helped organize the project. The brothers graduated and went on to medical school at Vanderbilt University, where they continued networking, planning and fundraising. Once the clinic opened, Milton and Fred helped found a nonprofit called the Lwala Community Alliance (LCA). Beyond providing healthcare through more than 33,000 patient visits a year, the LCA focuses on community wellness, including public health outreach, education, small-scale micro-enterprise, and classes on sanitation. “We’re trying to attack the problem of poverty and ill health in a holistic way,” Fred says.

The annual budget for LCA has grown to $1.3 million and supports a range of initiatives. In 2011 the clinic expanded to add a maternity and integrative care wing. As a result, the number of women in the village delivering babies in a healthcare facility rather than at home increased from 26 percent to 96 percent—twice the national average—and the infant mortality rate has been halved, from 60 to 31 out of 1,000 children. Last September they launched Thrive Thru 5—a program to cut child mortality in Lwala by 50 percent by 2016 and ensure that at least 90 percent of local children are fully immunized by age 1.

As depicted in a 2011 documentary, Honoring a Father’s Dream: Sons of Lwala, the brothers continue to live in two worlds. While they work to improve regional healthcare through LCA, they also practice medicine in the United States, Milton in internal medicine and gastroenterology in St. Louis, Missouri, and Fred through his last year of a residency at Vanderbilt in internal medicine and pediatrics. They credit their education with helping them achieve their goals. “If it weren’t for the friendships and connections that we made at Dartmouth, I don’t think we would have been able to realize our full potential,” Milton says. —Carolyn Kylstra ’08

Femi Allen Wasserman ’99

A Fantasy Life

How does the only African-American female executive in the daily fantasy sports industry feel about her ceiling-shattering role? “I have never thought about that,” says Wasserman, vice president of communications and spokesperson for DraftKings, the largest U.S.-based daily fantasy sports gaming site in the country. “The ‘black female executive’ part is wonderful, but it doesn’t define me. I never let messages stop me from doing what I wanted.” Growing up in Chicago, Wasserman was a self-professed “nerdy, sci-fi, mathy type,” and often the only black girl at citywide math competitions. “I got used to that feeling early, being the only person like me in the room.”

The trend continued at Dartmouth, where she majored in math. Wasserman then went into finance, working as the director of product development at Capital One, taking time to earn her M.B.A. from Harvard Business School in 2007. In 2012 she joined Boston-based DraftKings, where she creates customer support, technology systems and communications strategies. The daily fantasy site offers short-term fantasy sports leagues. For example, for the NFL, a participant drafts a new team every week, with the player pool determined by the games that are being played that week. Including its mobile and online offerings, DraftKings counts 1 million registered users and will award more than $200 million in cash prizes this year, Wasserman says. Although she has helped DraftKings grow since it launched in the spring of 2012, Wasserman now works half-time while she and her husband raise five children. “I couldn’t be afraid to ask for what I needed in order to have the life I wanted,” she says. —Abigail Drachman-Jones ’03

Norman Bay ’82

Federal Energizer

Bay’s first experience with the U.S. Senate confirmation process was a breeze. In June 2000 President Bill Clinton nominated him to be U.S. attorney in New Mexico. That September Bay was confirmed by unanimous consent, 96-0, making him among the first Asian-American U.S. attorneys in the country. Last January President Barack Obama nominated him to chair the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Bay, who’s spent the past five years as head of FERC’s office of enforcement, was approved, barely, by a vote of 52-45 in July. “This past confirmation was a difficult one,” says Bay, who from 2002 to 2009 was a professor at the University of New Mexico School of Law, where students voted him “Best Law Professor.” “Nothing would please me more than to earn the respect and trust of senators who did not support me.” Bay, who is the first Asian-American commissioner, has three top priorities in his new role at FERC: improving infrastructure (including gas pipelines and transmission lines), the efficiency of the markets and the electric grid’s reliability. “Most people have no idea what has to happen for the light to go on when you flip the switch,” he says.

Bay grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where his father worked as a civilian for the Air Force and his mother was a chemist. After graduating from Harvard Law School in 1986, he spent more than a decade in the U.S. Department of Justice, much of it in the violent crime section of the U.S. attorney’s office in New Mexico. In 2009 he became FERC’s enforcement director, and helped return nearly $1 billion to taxpayers after investigating the gas and electric markets. Now he’s focused on the transition from coal to gas, the increasing use of renewable energy and EPA rulemakings. “It’s a time of great change in the energy space,” he says. —Abigail Drachman-Jones ’03

Lindsay Earls ’05

Tribal Citizen

Earls spent much of the past year—her first as legislative counsel of Cherokee Nation—preparing for the United Nations’ first World Conference on Indigenous People: She spoke at meetings, collaborated with the Indian Law Resource Center and helped the nation’s secretary of state prepare his address to the September gathering. It wasn’t Earls’ first interaction with a legal system. She was a plaintiff in Board of Education v. Earls, which challenged her high school’s policy of mandatory drug testing of students participating in extracurricular activities (the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the testing in a 2002 ruling). But Earls wasn’t aware federal Indian law existed until she studied it during her Sophomore Summer. “You don’t really see federal Indian lawyers advertising on TV,” says Earls, who majored in government. Native American studies courses inspired her to study international indigenous law at the University of Tulsa.

One of her main responsibilities is to write the nation’s comments on federal proposals, particularly on issues of housing and healthcare. From tribal headquarters in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, she frequently travels to meet with lobbyists and congressional representatives in Washington, D.C., and Oklahoma City. Her role has earned her a spot on the 2014 “Native American 40 Under 40” list by the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development.

Earls says the Cherokee government is organized much like the U.S. federal government and has many of the same concerns of local governments everywhere: safety and clean air and water. She points out that investments the tribe makes in areas such as education benefit society as a whole, not only tribal citizens: “Where we help our tribal citizens, all boats rise.” —Cynthia-Marie O’Brien ’04

Jonathan Meyers ’07

Safe and Secure

Sure, the best-laid plans often go awry. But in the summer of 2011, when environmental engineer Meyers arrived at a construction site to find a confusing disarray of blueprints and other building plans, he’d had it.

“I said, ‘I’m going to have to shut this project down if we don’t have some consensus,’ ” Meyers recalls. “At the end of the day I was feeling nerve-wracked and tired.” And then he had a dream—a real one. “It was 4 in the morning and I dreamed I had access to everything immediately on some sort of e-portfolio.”

Meyers now has a new job title: CEO of Baltimore-based PrintLess Plans. The company’s first product is the 21-inch folding, rugged Zephyr tablet—the “Patagonia-wearing cousin of Amazon’s Kindle Paperwhite,” according to Architect magazine—designed to handle digital architectural drawings and engineering schematics. And if he finds any problems on site, handwriting recognition software enables him to make notes on digital PDFs and send copies off to everyone involved. Studying engineering sciences and studio art at Dartmouth, says Meyers, gave him the product-design background for the invention, but bringing it to market was challenging. He returned to Hanover for help, working with a class at Thayer School of Engineering to conduct a feasibility study and build initial concept designs. “An idea isn’t worth anything until you’re able to make some physical, tangible manifestation of it,” says Meyers, who launched a prototype at a green-building conference in 2013. The response? “It’s been overwhelmingly positive,” says Meyers, who’s happy to have cleared away the clutter. “Instead of lugging around multiple sets of heavy paper plans and drawings in the back of my truck, I can access everything with my Zephyr,” he says. “It helps cut down on costly errors that arise from outdated plans because I have access to the latest information in the field.”

And that leaves him free to dream up the next big on-site idea. —Sarah Tuff

Sarah Weiner ’02

More Than Good Taste

Crème brûlée and the scientific method were the obvious topics for food-lover Weiner’s college application essay. Now she puts her lifelong passion for food to use as the cofounder and director of the San Francisco-based Seedling Project, which funds projects to engage the public, and the Good Food Awards, which she created to recognize the best food producers in America while redefining what “best” means. “It’s not just about the taste,” Weiner says, “but also about sustainability and social responsibility.” In categories ranging from beer to charcuteries to pickles, the Good Food Awards single out exceptional producers (goodfoodawards.org/winners). This year, to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the awards and a record-high 1,462 entries, Weiner is launching the Good Food Mercantile, a trade show to highlight sustainable foods.

After receiving her degree in economics and attending culinary school in Italy with the support of a Dartmouth Reynolds Scholarship, Weiner got her start in food working at Slow Food headquarters in Italy, then became the assistant to Chez Panisse chef and sustainable food advocate Alice Waters (who was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people of 2014). “There’s a way to be conscious about making the world a better place that ties to food,” Weiner says. “There’s a way to align good taste and respect that is not all about sacrifice.”

Although it keeps her busy, Weiner’s job isn’t all about sacrifice. “I just got off the phone with a capital punishment lawyer-turned-chocolate maker,” she says. But the best part of the job? “The people,” Weiner answers without pause. “And the leftovers.” —Rianna P. Starheim ’14