The president was skeptical. A faculty committee stood ready to nix the idea on the grounds that it might create a riot in the dorms. “We had to go in and face the most hostile group, which saw no reason to have a radio station at Dartmouth College,” Richard Krolik ’41 later recalled. “We collected all the evidence we could and we summoned forth the essays on freedom of speech and God knows what and we sat there and banged the table.”

President Ernest Martin Hopkins, class of 1901, had reason to be skeptical. Seventeen years earlier, in 1924, he had approved a proposal by the radio club to launch a student-run AM broadcast station at Dartmouth. It operated for about a year but was shut down after an incident in which profanity was accidently broadcast. It was 1941 before, reluctantly, Hopkins let students try again, this time under strict faculty control.

Subsequent stations have had a remarkable history, and many alumni regard their years at campus stations as more than just an extracurricular activity. Most of them went on to careers in fields other than broadcasting, but many feel their radio experience was vital in shaping their lives.

“WDBS was my most satisfying and productive classroom,” says Dave Dugan ’52. “WDCR did more for me than my Dartmouth education,” adds Charlie Smith ’73.

“It was good experience in making it in a man’s world, helping me gain confidence and assertiveness,” says Kathy DeGioia-Eastwood ’76.

Krolik’s station, called DBS, got off to a strong start, but World War II intervened and in 1943 it was forced to shut down due to a staff shortage. Returning senior and former Navy pilot Robert Varney ’43 revived it in the spring of 1946. Two years later new College President John Sloan Dickey ’29, in a historic move that would shape the future of Dartmouth radio for 50 years, dissolved the faculty-dominated Radio Council and turned over operation of the station entirely to the students. Dickey remained a strong advocate of station independence for the rest of his 25-year tenure, giving Dartmouth students a unique laboratory in which they learned to run a real business, one with an influential voice in the community.

Students rose to the challenge, making DBS (now called WDBS) an increasingly professional operation. Among the leaders of this era were station manager John Gambling ’51, later a major New York radio personality, Don Hyatt ’50 (producer of acclaimed documentaries including NBC’s Project Twenty), Jim Rosenfield ’52 (president of CBS-TV) and Herb Solow ’53 (a TV executive responsible for Star Trek and Mission: Impossible). Shows included Jam for Breakfast, the long-running Music Till Midnight, and Bedpan Alley, which featured music to soothe the residents of Dick’s House infirmary.

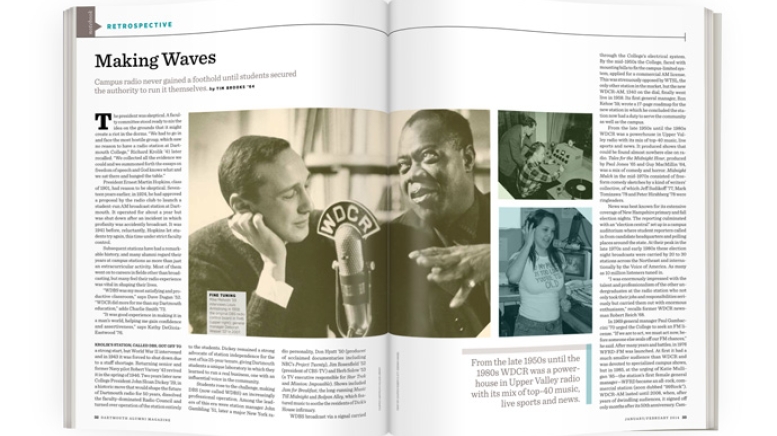

WDBS broadcast via a signal carried through the College’s electrical system. By the mid-1950s the College, faced with mounting bills to fix the campus-limited system, applied for a commercial AM license. This was strenuously opposed by WTSL, the only other station in the market, but the new WDCR-AM, 1340 on the dial, finally went live in 1958. Its first general manager, Ron Kehoe ’59, wrote a 17-page roadmap for the new station in which he concluded the station now had a duty to serve the community as well as the campus.

From the late 1950s until the 1980s WDCR was a powerhouse in Upper Valley radio with its mix of top-40 music, live sports and news. It produced shows that could be found almost nowhere else on radio. Tales for the Midnight Hour, produced by Paul Jones ’65 and Guy MacMillin ’64, was a mix of comedy and horror. Midnight Mulch in the mid-1970s consisted of free-form comedy sketches by a kind of writers’ collective, of which Jeff Sudikoff ’77, Mark Tomizawa ’78 and Peter Hirshberg ’78 were ringleaders.

News was best known for its extensive coverage of New Hampshire primary and fall election nights. The reporting culminated with an “election central” set up in a campus auditorium where student reporters called in from candidate headquarters and polling places around the state. At their peak in the late 1970s and early 1980s these election night broadcasts were carried by 20 to 30 stations across the Northeast and internationally by the Voice of America. As many as 10 million listeners tuned in.

“I was enormously impressed with the talent and professionalism of the other undergraduates at the radio station who not only took their jobs and responsibilities seriously but carried them out with enormous enthusiasm,” recalls former WDCR newsman Robert Reich ’68.

In 1969 general manager Paul Gambaccini ’70 urged the College to seek an FM license. “If we are to act, we must act now, before someone else seals off our FM chances,” he said. After many years and battles, in 1976 WFRD-FM was launched. At first it had a much smaller audience than WDCR and was devoted to specialized campus shows, but in 1985, at the urging of Katie Mulligan ’85—the station’s first female general manager—WFRD became an all-rock, commercial station (soon dubbed “99Rock”). WDCR-AM lasted until 2008, when, after years of dwindling audiences, it signed off only months after its 50th anniversary. Campus programming transitioned to the Internet. Meanwhile 99Rock has become a major player in Upper Valley radio, with ratings usually among the top-five stations. With its state-of-the-art studios, it continues to provide students with experience in radio broadcasting and business management.

The days of all-student control are over, however. A fulltime operations manager, Heath Cole, now runs 99Rock with a dedicated student staff. As onetime general manager Jordan Roderick ’78 (who with fellow techie Ted Bardusch ’76 built the original FM studios) once wrote, “No one would have bothered to do all that work if this were just a radio station. Dartmouth Broadcasting is one of the few organizations on campus that is made up entirely of dreams and hope and creative energy run amok.”

Tim Brooks, a former station staffer, is an author and former network television executive. He recently published College Radio Days: 70 Years of Student Broadcasting at Dartmouth College. He lives in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Bathroom Records and Huskies in the Night

Putting on the hits was often an adventure, as these airwave anecdotes attest.

>>> Professor Robin Robinson (affectionately nicknamed “Rob-Rob”) presented classical music on Dartmouth radio for 47 years, until his death in 2002 at the age of 98. In his later years he would sometimes doze off during his show. Student engineers were instructed to wake him 30 seconds before the end of a selection so he could resume his narration.

>>> A 2003 sex-education show called In Your Pants tackled such questions as “Where can I get sex toys in Hanover?” and “Is it safe to have sex in the water (or the river)?”

>>> Sportscaster Dave Title ’79 got a little excited during live coverage of a 1978 Dartmouth vs. Notre Dame basketball game that turned out to be unexpectedly close and uttered these words: “Holy shit! I can’t believe this!”

>>> In 1981 Lucretia Grindle ’83 produced a radio adaptation of Dracula. To create the sound of Dracula’s wolves, she found a veterinarian near White River Junction, Vermont, who had huskies that howled nightly as the Montrealer train passed through. She waited patiently one zero-degree night, recorder in hand, waiting for them to “do their thing,” she recalls.

>>> The longest charity marathon in station history was endured by Bill Aydelott ’72 in 1971. He lasted 129 hours—possibly the longest single DJ marathon in U.S. radio history at that time. Staffers brought in his high school drum kit to keep him awake. “About 10 minutes with the trap set would get me going for another hour,” he says.

>>> Technical director Ted Bardusch ’76 may hold the distinction of being the only student to literally “die” for the station. While he was repairing the AM transmitter in the spring of 1975 it shorted out and electrocuted him, stopping his heart. Fortunately he had imposed a rule that required “two minimum go to the tranny shack” and had trained everyone in CPR. Bardusch’s companion that day, Bill Taylor ’75, was able to revive him.

>>> Disc jockeys of the 1960s kept a “bathroom record” handy, which ran long enough to allow them to run down to the second-floor bathroom and back when necessary. In the early 1960s it was Marty Robbins’ “El Paso” (4 minutes, 40 seconds in length). DJs of the late 1960s apparently had weaker bladders—they used The Beatles’ “Hey Jude” (7 minutes, 20 seconds).

>>> One of the most notorious broadcasts of the 1940s was a radio play called It Can’t Happen Here, presented on DBS Workshop in 1948. It consisted of an ordinary music program that was interrupted by a series of urgent news bulletins reporting a sudden Soviet attack that leveled Portland, Maine, and eight other U.S. cities. It was supposed to be a morality play about complacency, but many listeners thought it was real and flooded the station and police with panicked calls.

>>> A well-remembered program of 1951 was the late-night Your Lonesome Gal, during which a sensual female purred and cooed, told the listener she loved him and then importuned each individual “sugar” listening to go out the next morning and buy some Bondstreet pipe tobacco.