The Rambler

In September 1935, following a brief stint at Harvard Business School and a summer selling maps in Connecticut, Harry “Espy” Espenscheid sailed to Europe aboard a freighter. “There was a queer feeling inside,” he confessed in his journal, “when I thought of setting out on a two-year vagabond ramble while college contemporaries were boning away at their professions.” But Espenscheid’s late mother had instilled in him a love of geography, and he was determined to see the world before losing what he called “the strength and zest of youth.”

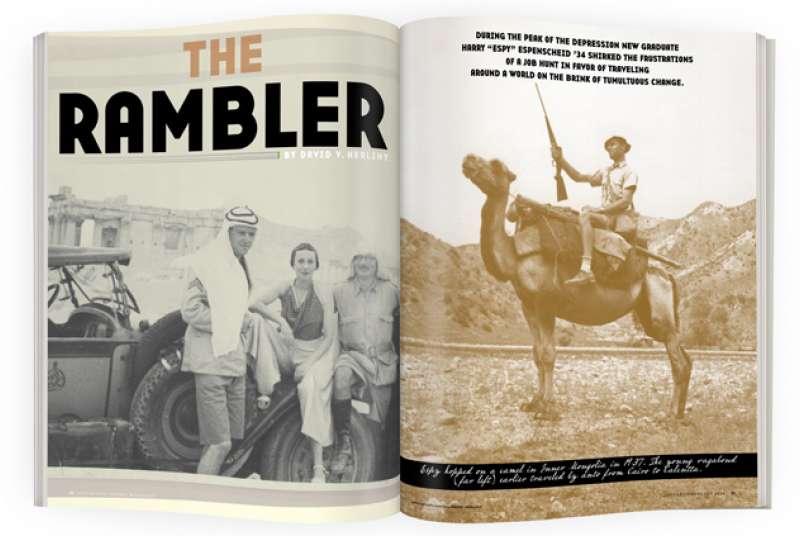

So off he went, traveling thousands of miles to visit 31 countries—all on a budget of $1,100. He wrote a diary along the way, as well as a newspaper column. And he took a camera.

It all began in London, where Espy bought a sturdy three-speed bicycle to haul his 6-foot-3-inch frame and 50-pound Norwegian rucksack around rainy but bicycle-friendly Great Britain. In Cambridge he visited an old Dartmouth friend, Bill Fitzhugh ’35, who was studying history at Trinity College. “Our system is cramming and slave driving, theirs is a process of absorption,” Espenscheid wrote in his column for his hometown newspaper, the Danville (Illinois)Commercial-News. Still, he noted, student life was harsh. Proctors’ agents, dubbed “bull dogs,” prowled the pubs at night to nab delinquent students.

In Germany the people were friendly and neat. And life was affordable—a hot meal or a room cost but a quarter. In Munich, a “capital of beer and music,” Espenscheid bought a used single-speed bicycle for less than $10 to replace the three-speed he left in England. He then pedaled through picturesque medieval towns along the Rhine, observing the townsfolk in traditional garb and lively street celebrations.

The traveler detected an ominous chill in the air. Four years earlier he had visited this impoverished land, still recovering from the Great War. “Not once do I remember seeing troops,” he wrote home. “Now I see them every day.” Clearly, the new Nazi regime was frantically rearming, and Europeans seemed blithely resigned to the inevitability of yet another war. “They know it will come just like birth and death,” he told his readers, “[though] the masses surely want peace.”

“I am not pro-Hitler,” he insisted in his column. “I would not want him at the head of our government.” Still, he noted, the economy had improved under the Nazis, despite the continued rationing of eggs and butter and the overt persecution of Jews. “Hitler has given Germany law and order,” Espenscheid declared, “and for the working class he has done much. It is true that those who do not like Hitler are afraid to speak openly, but the majority are strongly in favor of him.”

In February 1936, while attending the Winter Olympic Games in the Bavarian resort of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Espenscheid came within 60 feet of the German dictator. “We were close to the balcony where Hitler watched the contestants,” Espenscheid reported. “A splendid opportunity to gape. We watched Hitler more than the ski jumping. Der Fuhrer made a good impression. But Goering is a brutal, arrogant-looking man. Dr. Goebbels impresses one as being clever, shrewd and unfeeling.”

At the games Espenscheid reconnected with three Dartmouth pals, all members of the U.S. ski team: Richard “Dick” Durrance Jr. ’39, Albert Lincoln “Link” Washburn ’35 and Edgar Hayes “Ted” Hunter Jr. ’38 (a future Dartmouth professor of architectural design).

From Garmisch, Espenscheid cycled with Fred Birchmore, a recent graduate of the University of Georgia. To reach Innsbruck, Austria, they negotiated treacherous mountain passes during a snowstorm. In fascist Italy they were briefly detained as spies. They continued down the rugged Dalmatian coast, pausing periodically to celebrate the carnival season with the colorfully dressed locals before reaching Dubrovnik, where they caught a ferry to Athens.

In Cairo Birchmore continued east by bicycle while Espenscheid teamed up with a German explorer named Walter Kahler, who had driven a 7-year-old American-made roadster from Berlin. He offered to drive Espenscheid as far as Calcutta. The trip, sanctioned by the German and Egyptian automobile clubs, was designed to assess driving conditions along the old caravan road, where automobiles were a rarity.

To prepare for the desert stretches they installed extra springs and two auxiliary tanks, one for gasoline and the other for water. As a final touch they painted on both doors the Arabic expression, “Innsh’Allah!” meaning “God willing.” “We planned to cook our meals and sleep outdoors most of the time,” Espenscheid explained in his memoir. “In the Cairo bazaars, after much haggling, we purchased a Swedish primus stove, canteens, a couple of pots and provisions such as rice, soup cubes, dried fruits and cheese.”

After visiting the great pyramids of Giza they headed to Suez, already scorching in April. While waiting for a ferry to cross the canal they observed an Italian ship bound for Ethiopia, loaded with Mussolini’s soldiers. Plunging into the Sinai desert, Espenscheid and Kahler were pleasantly surprised to find an asphalt road—until they realized their tires were sinking into the melting tar. Then came the sand. At times, to go forward they had to drive over the planks they had cleverly thought to pack. They plodded along in first or second gear, barely making 20 m.p.h. At night they feared a surprise attack by Bedouins.

In Amman, Jordan, then in Jerusalem, Palestine, they found themselves in the midst of anti-Jewish riots. Only by dressing up as Arabs and following a police escort did they emerge unscathed. Espenscheid’s conclusion: “The British blundered badly by promising the same land to two peoples.” Life was hardly more harmonious in Damascus, Syria. Nearly every business had been closed for two months to protest French rule. It was almost a relief to return to the desert.

In Baghdad the motorists drew large crowds of curious citizens, as well as a wave from the king himself. Still, they felt uneasy. “Iraq is not exactly a peaceful country,” Espenscheid wrote. “In the south, a nice little revolution was going full blast. Up in the north, among the mountains, the police are always fighting with the Khurds.”

Espenscheid found Iran “intensely interesting,” The shah, he wrote, “is modernizing his country and carrying out his reforms with an iron fist. A few years ago the people all wore their native dress, men wearing the turban and women the veil. Now all is changed. Only an autocrat could do that in such a short time.”

After passing through the holy city of Mashhad, Iran, the motorists crossed into Afghanistan—just ahead of a hail of bullets. Unwittingly they had sailed past the station housing the border police. They were taken into custody but released after they produced the proper papers. After another grueling desert stretch they reached Kandahar. Their frequently blown tires were now entirely shot. Facing a long wait for spare parts, the two decided to abort their mission and sell the roadster for spare change.

Espenscheid spent the next five weeks roaming West Tibet and Kashmir on horseback, always staying at least 8,000 feet above sea level. He admired the ubiquitous “red and yellow lamas,” the monasteries and the carefree lifestyles. He pronounced the locals “the most fantastic people imaginable.” The stunning sunrise illuminating the as-yet-unconquered Mount Everest, he concluded, made Mount Washington “look like a molehill.”

After an extensive tour of India, including a visit to the Taj Mahal and a tortuous journey through the jungles of Assam, where he had to dodge headhunters, Espenscheid reached Burma. Having contracted malaria, he spent nearly two weeks recovering in hospitals in Rangoon and Mandalay.

For four months Espenscheid lived with a German painter on the island of Bali, paddling canoes and observing native dances. He finally pulled himself away to Singapore, Cambodia and French Indochina. He reached China and Mongolia in the summer of 1937, just as the Japanese were invading both countries. For several weeks he was among the foreign refugees camped out at the American embassy in Beijing, then called Peiping.

Luckily, Espenscheid managed to catch a steamer to Japan, then another one heading across the Pacific Ocean. He was immensely proud that he was among the few to have made “a southern crossing of Asia entirely by land.” He felt lucky to be alive, personally enriched and ready at last to get on with his life—at home in the United States.

While later operating a dude ranch in Wyoming he met his future wife, Dorothy Sharp. They settled in Rockport, Illinois, where Espenscheid made his mark buying and selling construction companies. He died in 2011, just shy of his 98th birthday.

David V. Herlihy is the author of Bicycle: The History and The Lost Cyclist. He lives in Boston.