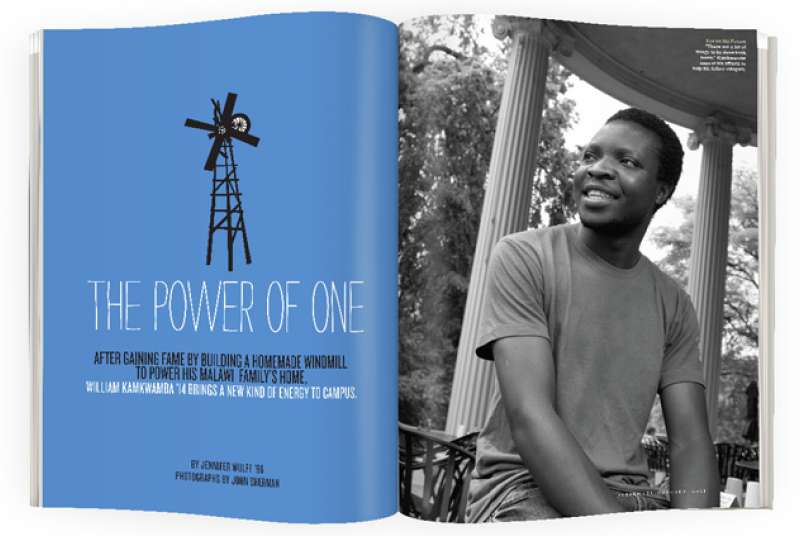

The Power of One

He tackled a paper on Nietzsche’s Antichrist in his freshman writing course, built heat- and compressed-air-powered engines in Thayer’s machine shop and even learned how to play ice hockey during one of Hanover’s most intense winters in recent years. Asked about the difficulty of those feats, or his adjustment to the countless day-to-day changes he’s faced since moving to the United States from his village in Malawi, William Kamkwamba just shrugs and smiles. But there’s one thing at Dartmouth he still can’t wrap his head around: pong. “What is this strange game?” he says. “Back home, if you want to drink, you need money to do that. Here, if you are just bad at pong, you get to drink a lot for free. That is definitely something different.”

Although being schooled in the goings-on of the Bones Gate basement doesn’t seem as fundamental as what he’s learned in the classroom, observing Dartmouth’s social scene is as much an educational endeavor as anything else for Kamkwamba (who doesn’t drink). “It’s such a different culture here,” he says. “I need to have some knowledge of what goes on at these parties. I find it very interesting.”

It’s that same curiosity that inspired Kamkwamba, whose 2009 book The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind spent five weeks on The New York Times bestseller list, to build his own homemade windmill at the age of 14. During Malawi’s deadliest famine in 50 years, when he was forced to drop out of school because his family could no longer afford the $80 annual tuition, he checked out a book called Using Energy from the library in his small village of Wimbe. Relying mostly on illustrations to aid him, since he could barely read English at the time, Kamkwamba came up with a plan to power his family’s home. This in a country where the thought of a poor maize farmer’s family having electricity was unheard of: Only 2 percent of the population enjoys such a luxury.

Kamkwamba spent weeks at the local scrap yard, which happened to be right across the road from his former school, searching for any type of material that might prove useful. Meanwhile, his former classmates mocked him, calling him misala, which means “crazy” in his native language, Chichewa. Even his mother thought he’d lost his mind. But within a few months the young MacGyver had pieced together bottle caps, bicycle and tractor parts and the rubber from a pair of worn flip-flops to craft his 16-foot-tall wonder. His family and neighbors stood aghast as Kamkwamba climbed to the top of the rusty, rickety structure and hooked up his first light bulb, which suddenly—magically—glowed with a gust of wind. He soon wired his whole house and added a circuit breaker, step-up transformer and battery. Locals eager to charge their cell phones began lining up outside the Kamkwamba home.

“To start with nothing and end up with a fully fledged windmill that produces power is an extraordinary move,” says engineering professor John Collier ’72, Th’77, who is Kamkwamba’s advisor. “And to do it all with no tools except for some nails? I don’t think there’s a doubt in anyone’s mind that he’s a natural at this.”

Now that he has access to the machine shop at the Thayer School of Engineering, which stocks tools and materials he couldn’t even dream of in Africa, Kam-kwamba is delving into many more projects. “We’re working now on computer-aided design [CAD], which will give him a real boost,” says Collier. “He’s got a great imagination and big plans, so CAD is perfect for him.” This summer, after a month-long trip back home, Kamkwamba, who turned 24 on August 5, spent the rest of his off-term in Hanover to enjoy more time in the shop. After all, that was what drew him to Dartmouth in the first place. “At other schools you could maybe use the machines in your senior year, but here I could use the shop as a freshman, so I thought this was better suited to me,” he says. “I’m definitely more of a hands-on person.”

Unfortunately, his shop time is often limited because of the tremendous amount of studying he needs to do. “I’m sometimes up all night trying to do my work,” says Kamkwamba. In addition to his regular classes he’s also working with a math tutor to gain more experience with calculus before diving into advanced engineering classes. “He works incredibly hard,” says his roommate, Varun Ravishanker ’14. “I’ll be in bed for two hours by the time he gets back from the library.”

Kamkwamba’s can-do spirit became the unofficial theme of the 2007 TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) global conference in Arusha, Tanzania. After the story of his windmill traveled from the local papers in Malawi and into the blogosphere, he was chosen as one of 100 fellows to attend the biannual gathering of great minds. As soon as TED community director Tom Rielly met Kamkwamba, who was still reeling from his first plane ride and the experience of sleeping in a hotel for the first time, Rielly asked if he’d mind answering a few questions on stage.

“Even in just a few minutes, in his halting English, and shaking because he was so nervous, he had people laughing and crying and he got a standing ovation,” says Rielly. “And he said something that became a touchstone of the conference, which was, ‘I try, and I made it.’ People just kept repeating that phrase over and over in the most delighted way.”

Rielly was so taken by the story he went back to Malawi with Kamkwamba to see the windmill firsthand. Moved to tears when he saw the beauty of the structure on the dusty horizon, and even more wowed when he saw the intricacy of Kamkwamba’s wiring work, Rielly soon made a commitment to help Kamkwamba get through high school and college. “I didn’t go into the decision lightly,” he says. “Africa is filled with people with good intentions who get excited about something and then don’t follow through. So I said I’m going to make a seven-year promise. That way William would know that the rug wasn’t going to be pulled out from under him.”

It’s now year four and Rielly, who helped enroll Kamkwamba in a Christian school in Malawi’s capital city, Lilongwe, and then South Africa’s prestigious African Leadership Academy outside Johannesburg, remains a trusted mentor and close friend in Kamkwamba’s life. The two text often and speak weekly. Rielly and his friend Andrea Barthello, owner of the educational game company ThinkFun, even came to Hanover for Family Weekend last spring. “We jokingly refer to ourselves as William’s American mom and dad,” says Rielly, 47, who lives in New York City. “I don’t want him to feel smothered, so we try not to be helicopter parents.”

It was in that vein that Rielly did not steer Kamkwamba to any college in particular when it was time for him to start applying. But Rielly did make a list of potential engineering schools on both coasts and in the South for him to look at while on his U.S. book tour in the fall of 2009. Kamkwamba visited Southern Methodist University, Virginia Tech and Harvey Mudd, among others, but it wasn’t until after a TV appearance with his coauthor Bryan Mealer (a former AP correspondent) that Dartmouth was even a consideration. Waking up to Good Morning America one day, Thayer’s then development officer Carol Harlow saw Kamkwamba interviewed by Diane Sawyer and knew she had to get in touch. Harlow googled him and found Kamkwamba’s e-mail address, then insisted he make the trek to Hanover.

At that point Kamkwamba was exhausted, but “she wouldn’t let up,” says Rielly. After touring the campus and meeting with President Jim Kim and a number of engineering students, there was no question that Dartmouth was where Kamkwamba belonged. It was Thayer’s tool library that most dazzled him: To borrow power tools was the ultimate thrill for the born tinkerer. “There’s a touch-screen monitor where you can see what’s available to check out, and I remember him going to the ‘power supply’ menu. He just lit up when he saw all the results,” says Harlow, who now runs her own consulting business. “For someone who built something so impressive out of nothing but scraps in his village, he suddenly saw this whole universe open up for him.” Following the tour of Thayer, where he later gave a standing-room-only talk, Kamkwamba sat down with Kim, who rarely meets with prospective students. “I am inspired just thinking about what he has done, what he will do for the Dartmouth community while he is here, and what he will do for the world when he leaves,” Kim says.

While Kim’s warm welcome made a huge impression, what also appealed to Kamkwamba was the idea of a liberal arts education. Engineering is his primary interest, but it’s not the only one. He’s taken drawing and photography classes, tried out for the cheerleading team (“just for fun,” he says; he didn’t make it) and is considering earning a drama credit or two. “It might be a little difficult with my accent,” he says. “But maybe if I do a British accent instead. How’s this: ‘Would you like some wahhhhta?’ ”

If his success with the other challenges he’s faced at Dartmouth is any indication, he’ll be stage-ready in no time. Arriving without the strong foundation of a prep-school background or even the secondhand experience of having any relatives or friends attend college before him, the adjustment was difficult. As co-author Mealer explains, though Kamkwamba “is one of the most creatively resourceful people I’ve ever met,” understanding the theories behind the projects was often not a priority until now. “When we were doing the book I’d ask him how a circuit breaker works and he’d say, ‘You know…there’s like a fight between the magnets,’ ” says Mealer. “I’d be like, ‘Yeah, but how does it work?’ So we had to get a physics expert to fully explain it.”

Kamkwamba has a whole team of experts to turn to now. With Collier in his corner, as well as any number of students eager to lend him a hand if he needs it, Kamkwamba credits Dartmouth’s strong support system for keeping him afloat. “Something I am very glad about is this sense of community here,” he says. “I feel like even though my family is very far away, I have a kind of family here that can help me in whatever I want to do.”

Kamkwamba has built a circle of friends without flaunting his best-selling author status or the fact that he’s been a guest on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. In fact, he’s kept a very low profile on campus so far, even asking professors in the know to keep his background under wraps. Now that he’s settled in, he’s more comfortable sharing his story, but it’s evident he’s liked for reasons other than his celebrity. On a recent walk from Collis to his Russell Sage dorm room, wearing a Patagonia jacket over a faded T-shirt with a map of Malawi on it, Kamkwamba gives a wave or a handshake every few yards. “I think I am well,” he answers one friend who asks how he is. Think? “See, I don’t know if I am well,” he explains. “I would need to ask a doctor that. Maybe I need some medicine and I don’t know it yet. So that’s why I say ‘I think.’ ”

It’s difficult not be charmed by these Kamkwamba-isms. His slightly askew view of the world is just one of the things that distinguish him both as a student and as a public speaker. (He’s given talks everywhere from Germany to Japan; he even spoke to a crowd of 8,000 at the University of Florida last fall when his book was picked as a freshman read.) “There’s something he has, some light, that people respond to,” says professor Karen Gocsik, who taught the writing class for international students in which Kamkwamba studied Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky. “I found it remarkable how his very presence changed the temperature in the classroom. It’s just a lovely thing to have him here.”

Becoming a big man on campus is hardly one of Kamkwamba’s goals, though. After suffering through starvation—during the devastating famine of 2002, when people were dying around him and he and his family were surviving on only four mouthfuls of porridge a day—life is far easier in Hanover. He can have unlimited cheeseburgers and pizza, two of his favorites, with a simple swipe of a dining card. But with so many challenges in his homeland, where cholera and malaria are as common as the cold is here, one out of five people has HIV, and the threat of drought continues to loom, Kamkwamba longs to return to Malawi.

“What worries me the most is how to solve some of the problems that my people are facing,” says Kamkwamba, who plans to join the Dartmouth Humanitarian Engineering Club as soon as he has more time. “So what I am always thinking about is how I can apply what I am learning here to help those at home.”

He’s already started. With money from donors as well as his share of the sizeable advance HarperCollins paid for his book, he’s built a deepwater well with a solar-powered pump that his entire village can access. Women there save two hours a day by no longer having to walk to the nearest public well. Crop irrigation is now possible as well, which not only lessens the likelihood of another famine but also allows farmers to grow more nutritionally diverse crops. He also just opened a nearby maize-grinding mill, which will earn money for his family and allow his 57-year-old father to hang up his plow for good. Of all things, though, Kamkwamba had to wait on Malawi’s central power company to fix a broken transformer first.

Through his nonprofit, Moving Windmills, Kamkwamba has also sponsored his village’s soccer team. It may seem frivolous to spend money on balls and uniforms when people are living in poverty, but it is turning out to be a phenomenal investment in both the players and the Wimbe economy. “A lot of the young people in my village were dropping out of school or smoking marijuana and drinking, which can lead to other bad behavior like contracting HIV,” says Kamkwamba. “So I came up with this idea of keeping these guys busy doing something positive.”

Half the village started showing up to watch the team (now ranked second in the district), including some able to earn extra money for their families by selling nuts and corn. Kamkwamba is now working to raise funds for bleachers, a proper field and a fence so the team can sell tickets and become self-sustaining. For the first time journalists are reporting on team matches. “Wimbe is literally on the map now,” says Rielly. “I didn’t get the whole idea at first when William brought it up, but when I saw my first game, I was like ‘Wow, this kid is smart.’ Giving the whole town something to root for? That’s subtle thinking to me.”

Out of his own pocket Kamkwamba is paying for private school for four of his six sisters (one of whom plans to be a doctor), a cousin and a friend as well as a few neighbors. He’d like the entire village to receive a proper education, though, which is why he’s also rebuilding the local primary school. With holes in the roof and craters in the cement floors, the 50-year-old current facility is not only dangerous but far too small for the 1,400 students who attend. Through Moving Windmills, which receives all of Kamkwamba’s honorarium money from his speeches, he has raised enough money to pay for four of the seven buildings that are needed. The structures are designed by buildOn, a nonprofit that requires the villagers it helps to do all the unskilled labor. “It takes longer, but it also means the community really wants the building and will take ownership of it,” says Rielly.

After installing solar panels on the one building already completed, Kamkwamba is also helping sponsor an evening adult literacy program, which teaches reading, agricultural education and AIDS prevention. “He thinks in such a systemic way,” says Rielly. “It was never just about a windmill. It’s about helping an entire community work better.” Kamkwamba’s ultimate goal: to bring low-cost power and water solutions to all of Malawi’s poor.

For now he’s working on getting through another day at Dartmouth, so it’s off to the library to hit the books. Again. “Ahhhh, the workload,” he says, shaking his head and chuckling. “That can be very challenging. But it can be done. When I focus and say, ‘I really need to succeed at this,’ I can do anything.” In other words, he’ll try, and he’ll make it.

Jennifer Wulff is a frequent contributor to DAM.