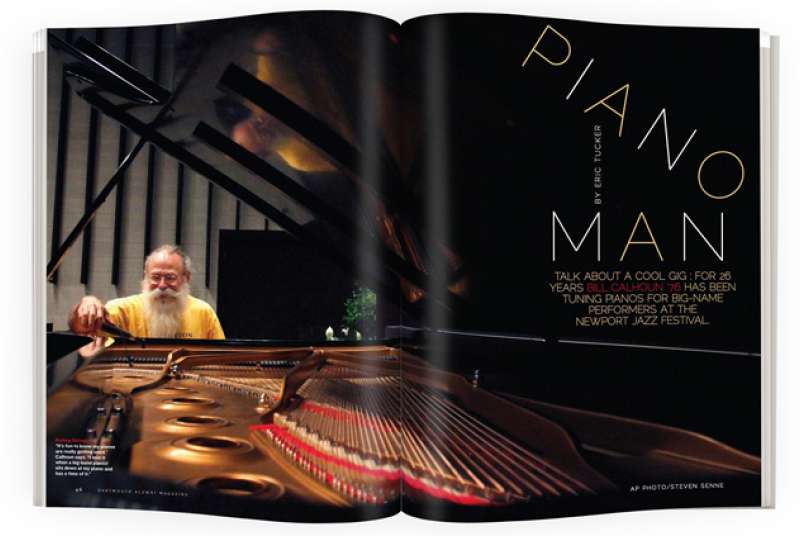

Piano Man

Between each act at the Newport Jazz Festival, as the audience cheers and crews clear the equipment, Bill Calhoun darts onstage with a fistful of tools and parks at the piano. He cocks his head, lowers his ear to the piano, taps ding-ding-ding on the keys, tinkers with a tuning pin here and there. When he’s done, he scurries offstage.

It’s a routine Calhoun has perfected. In August Calhoun marks his 26th anniversary as piano tuner for the celebrated Rhode Island jazz festival, which since 1954 has hosted such luminaries as John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie and Ray Charles. Calhoun generally has minimal interaction with the musicians, but his behind-the-scenes role is crucial to the festival’s success. When Dave Brubeck hits a note that rings just so, it’s a credit to his talent and a testament to Calhoun’s craftsmanship.

“The musician playing the piano has never played this piano before,” Calhoun says. “They’re going to walk on stage, introduce themselves to the audience and then sit down at a piano. In a sense my job is to make it so that they have total trust in what the piano can do for them and how the piano sounds.”

Newport performers take turns on the festival’s rented pianos rather than bring their own, creating the need for an on-site tuner sensitive to the instrument’s notoriously fickle nature: Humid weather, common during the annual festival, can knock the pitch out of whack. So can a pianist who pounds the keys especially hard.

“I’m insurance that the pianos will be in tune enough and in good enough repair,” explains Calhoun. Normally both he and the performers are too busy to greet each other, though sometimes they do. One time Chick Corea asked to meet Calhoun to feel him out and get a sense of the piano he’d be playing. The tuner has also met Dr. John—a pianist of a strikingly “gentle” style, Calhoun says, despite his “funny little meaty hands.”

One summer Calhoun found himself huddled beneath a piano with Herbie Hancock and his manager, investigating the source of a terrific BAM! that occurred after a structural piece at the instrument’s base fell during the Grammy winner’s performance.

“His manager looks at me and goes, ‘Are you the piano technician?’ I said ‘yes.’ He goes ‘good’ and looks at Herbie and says, ‘Herbie, get out of here!’ ” Calhoun recalls with a laugh.

As a boy, the Holbrook, Massachusetts, native was always more interested in trying to take apart his parents’ piano than in playing it, though he is a professional pianist. (He’s fond of bluesy jazz.) Coincidently, when Calhoun finally got his first piano in 1980 he had no choice but to dismantle it—he lived on the top floor of a triple-decker in Providence, Rhode Island, and it was impossible to get the instrument up the stairs in one piece. Months passed before he attempted reassembly.

Calhoun enrolled at Dartmouth to study physics and astronomy and, like other prospective students, he marveled at the beauty of the campus.

“I went, ‘Oh my God, it’s gorgeous,’ and Dartmouth seemed to be pretty impressed with me,” he says. Calhoun lived in the Wigwam dorms (known today as the River Cluster) and joined Sigma Phi Epsilon while busying himself with physics. “Something about the remoteness from the rest of the school, I think, tended to foster close associations with the rest of the kids down at the Wigs,” he recalls. Calhoun spent a semester with other physics students at the Kitts Peak National Observatory in Arizona, an experience he remembers as “wicked cool” since it gave him and his peers the chance to spend nights in a mountaintop observatory. While contemplating his future during senior year, he taught physics to students at Hanover High School.

After graduation Calhoun continued teaching high school science before finally deciding to blend his interest in music and physics. Driven in part by the enjoyment he had taking apart and putting together his first piano, in 1985 Calhoun entered the New England Conservatory to study piano technology. After completing the yearlong program, which required tuning and repair classes in the morning and hands-on practice in the afternoon, Calhoun was hired at the three-day jazz festival in 1986 after making what he calls a “ridiculously low” offer for his services. He’s been there ever since.

Calhoun shows up at 7 a.m.—hours before show time—and hangs with the sound engineers near the stage. He does full tunings and checks octaves at the start of the day, but between acts is when he really hustles—moving between performances on the festival’s three stages with a tuning wrench and pair of rubber mutes. Calhoun typically has a narrow window to test the strings that correspond to each note, check the octaves and finger the keys to make sure the sound is pitch-perfect.

“He’s very good and very fast, which you have to be,” says Bob Jones, a senior producer with New Festival Productions, the festival’s production company. “Sometimes there’s only 15 minutes between two piano players. He’s got to pipe right up on stage and make sure the piano’s in tune.”

“Calhoun is one of the festival’s many unsung contributors who return each year and are vital to behind-the-scene operations,” says festival manager Tim Tobin. “They feel as if it is a privilege to work for us because it is in fact the granddaddy of all jazz festivals.” In addition to the prestige, the festival’s intimate atmosphere is a magnet for the workforce. “When you’re working with your family, you tend to stick around,” says Tobin.

Calhoun echoes that sentiment. He’s been part of the festival family for so long that “they never call me anymore. They just assume I’m coming and wait for me to contact them.”

Even so, working a prestigious festival alone doesn’t pay the bills. Calhoun, a resident of Woonsocket, Rhode Island, juggles several jobs. His main gig is tuning and repairing pianos for performance halls and individuals. He also teaches high school physics part-time, runs workshops on the physics of music and tunes the pianos at the weekend-long Newport Folk Festival in July.

Calhoun says he’s tuned the piano of virtually every Newport performer in the last quarter-century, though one notable exception stands out. One summer Bruce Hornsby swung by Newport while on tour but enlisted his own keyboard player to tune his 9-foot Baldwin piano. It was, Calhoun politely suggests, perhaps not the best decision.

“Let’s just say had I tuned the piano it would have sounded better, but you know, Bruce Hornsby didn’t seem to care one bit what it sounded like.”

Eric Tucker is a reporter for the Associated Press in Providence, Rhode Island.