Looking back at the College’s history, one thing stands out in clear relief: Dartmouth has become a very different place from the one Eleazar Wheelock envisioned.

When Wheelock founded Dartmouth it never occurred to him that he or his school had anything to learn from Indian people. In his view, their ways of knowing and learning were simply primitive superstitions that must be eradicated if Indian students were to make any progress. In Wheelock’s vision for Dartmouth the few Indian students who attended were to be educated in English ways and Christianity so they could serve as missionaries who would convert other Indians to English ways and Christianity.

Not much changed as English colonial education for Indians gave way to American education for Indians. In 1819 Congress passed the Civilization Fund Act, providing for an annual appropriation of $10,000 to introduce “the habits and arts of civilization” among the Indians by employing “capable persons of good moral character, to instruct them in the mode of agriculture suited to their situation, and to teach their children in reading, writing and arithmetic.”

The act represented a commitment by the U.S. government to permanent involvement in Indian education, but it was an education to change Indians, the prevailing belief being that Indians could survive only if they ceased being Indians. With the establishment of government-sponsored boarding schools later in the century, the campaign to transform Indian children by eradicating their culture became a crusade. In 1891 Congress made school attendance mandatory for Indian children. Two years later it authorized the Bureau of Indian Affairs to withhold rations and annuities from parents who refused to send their children to school.

By 1900 congressional funding for Indian education reached almost $3 million, and 21,568 Indian students were enrolled in school. After the military subjugation of the continent, the United States waged a new war on Indian pupils to remake them into individual citizens, not tribal members. The schools tried to strip students of their Native languages, Native clothing, Native heritage and Native identity and provide them instead with minimal education and training to function at the lower levels of American society. Like British educational efforts in Ireland and the Highlands of Scotland, such campaigns, according to U.S. government policies of the time, “were designed to absorb supposedly deficient peoples into larger, dominant nations, leading not to cross-cultural fertilization but to the erasure of minority cultures and identities.” Indian education was “education for extinction,” cultural genocide waged with good intentions by people who sought to save Indians from themselves.

Yet, amid the hardship and heartbreak of the boarding schools, Indian students resisted the educational assault and refused to succumb to the assimilation philosophies and practices of their teachers. The students engaged in numerous small acts of subversion and rebellion, built bonds of friendship and loyalty with other Indian students and found humor and humanity in the midst of alienation and regimentation. Within the confines of the white man’s schools they created a subculture of survival and sustained their own Indian communities. Some used their education to pursue Indian agendas; many combined their Indian and Western educations in ways their teachers would never have sanctioned or even imagined.

Luther Standing Bear, the first Lakota student to attend Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania when it opened in 1879, looked back on the education he received and regretted the missed opportunities for creating a truly American school based on the fusion of Indian and Western systems of knowledge. Instead, he wrote, “we went to school to copy, to imitate; not to exchange languages and ideas, and not to develop the best traits that had come out of uncountable experiences of hundreds of thousands of years living upon this continent.” White people certainly had much to teach Indians, but Indians had much to teach them, too, wrote Standing Bear: “What a school could have been established upon that idea!”

Dartmouth could very easily have continued in the tradition of Wheelock and the boarding schools, less blatantly and less brutally but just as effectively de-educating Indian students as it prepared them for success in the non-Indian world. The late Lakota scholar and activist Vine Deloria Jr., author of books including Custer Died For Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (1969) and Indian Education in America (1991), delivered some scathing indictments of Western education.

He criticized mainstream colleges for training professionals but not producing people. Certainly, Native students can, if they wish, attend Dartmouth, graduate with the credentials and skills they need to succeed in mainstream America and have little to do with the Native community on campus, their Native community at home or their Native heritage. Although for some students Dartmouth is a path to a high-paying career rather than an opportunity to broaden the mind and feed the soul, the College does do more than make its graduates marketable. “Education is more than the process of imparting and receiving information,” wrote Deloria. “It is the very purpose of human society and…human societies cannot really flower until they understand the parameters of possibilities that the human personality contains.” Similar words and identical sentiments can be found in the speeches of past Dartmouth presidents James Freedman and James Wright, who steered the College into the 21st century with the firm belief that it should prepare students to live well, not just to make a good living.

Dartmouth is not—at least not yet—the kind of truly American school Luther Standing Bear longed for, but it is a far cry from the place Wheelock imagined. It is now an institution that recognizes value in diversity and a place where far more students embrace their Native identity than set it aside.

Living in a Native-American community, albeit a rather transient and academic one, sharing experiences with Native students from all over North America and having the opportunity to take classes that concentrate on Native issues can enhance Native students’ appreciation of their culture and identity, as well as increase consciousness of Native rights and sovereignty. Dartmouth can provide an environment where “Indianness” thrives—in the very place where Wheelock intended it should wither. The achievements of Native Americans educated at Dartmouth in recent decades speak to how well the College is fulfilling this contemporary objective.

At Dartmouth, as elsewhere, Native-American studies is still emerging as an academic discipline, and it is breaking new ground. Native and non-Native scholars explore issues of space, gender, artistic expression, representation, colonialism, indigenous sovereignty and nationhood as essential lines of inquiry in attempting to better understand the Native-American—and, therefore, the American—past and present. Students learn about Native-American ways of living, organizing societies and understanding the world. They also learn about relationships with colonial power and the unique rights and political aspirations of Indian peoples in the United States and Canada. Students explore the intersection of Indian and European histories and systems of knowledge as Native faculty at Dartmouth assign Locke, Rousseau and Foucault alongside tribal origin stories, the epic of the founding of the Iroquois League and the writings of Deloria.

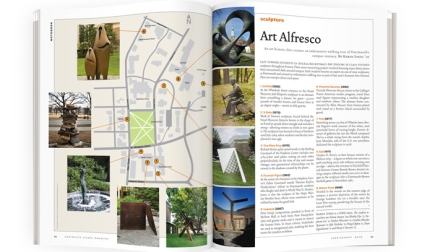

Dartmouth’s acquisition of the Mark Lansburgh ’49 collection of Plains Indian ledger drawings in 2007 illustrates how Indian education has changed since the College was founded. During 30 years Lansburgh assembled one of the largest and most diverse collections of 19th-century Native-American drawings in private hands. Historically Plains Indian warrior-artists depicted visual narratives of war and hunting on buffalo robes and teepees to publicly memorialize their heroic deeds.

From the 1850s through the 1870s, however, American expansion transformed life on the Great Plains. Smallpox, cholera and other alien diseases decimated Native populations, treaties lopped off huge chunks of Native American homelands and commercial hunting, aided and abetted by a government campaign of systematic slaughter, virtually exterminated the buffalo herds that had constituted the foundation of Plains Indian economy and culture. Relocated to reservations, Native people were subjected to government programs of “civilization” that replaced hunting with farming, outlawed their dances and rituals and took their children away to boarding schools.

As a result of exposure to American settlers, soldiers and government agents, Plains warrior-artists adopted new perspectives, themes, materials and styles to portray their personal experiences, and developed a unique genre using bound ledger books and lined paper. The drawings provide Native alternatives to the many romanticized and inaccurate representations of Plains cultures. The Hood Museum of Art now holds more than 130 ledger drawings, making Dartmouth a resource for the study of Plains Indian art. Ledger drawings generate intellectual and cultural discussions that range far beyond the Great Plains in their implications and relevance. Dartmouth is no longer an institution that thinks it has nothing to learn from Indians or its Native students.

In the first 200 years of Dartmouth College about 60 Native students attended. Since the College recommitted itself to honoring its founding pledge, more than 700 Native students from more than 160 tribes, Abenaki to Zuni, have attended. In the first years of the 21st century Dartmouth matriculated between 30 and 40 Native students every year. In the fall of 2009 the number passed 50. For the first time in Dartmouth’s history Native-American students composed 5 percent of the entering class, roughly five times the national rate of Native enrollment in degree-granting institutions. But Native-American students are not just statistics to show that Dartmouth is finally living up to its historic mission. They connect Dartmouth to Native worlds and worldviews that are lost to most of modern America, to tribal communities and concerns that seem far removed from a privileged Ivy League college, and to a constantly changing Indian Country that exists in eastern cities and Alaska as well as on western reservations. Indian students are an essential resource in creating the kind of educational environment that Luther Standing Bear hoped for, and they have been a major influence in the evolution and growth of Native-American studies at Dartmouth.

Nevertheless, despite a more congenial and relevant curriculum, a generally improved social and political climate and more educational and career opportunities than ever before, Dartmouth can still be a hard place to be Indian. What sustains Dartmouth’s Native students through difficult times is their fellow Native students. Year after year, following Dartmouth’s commencement ceremonies, Native graduates give personal testimonies acknowledging the support of friends and peers and declare that they would not have made it without their affinity group, Native Americans at Dartmouth. Like their grandparents and great-grandparents who grouped together and built their own communities to combat the homesickness, austerity and racism they confronted in boarding schools, so Native-American students have built a community at Dartmouth. The people Wheelock intended to change at Dartmouth have helped to change Dartmouth and ensured that, at least in some respects, Dartmouth is, after all, an Indian school. In the young Native-American men and women it attracts, educates and graduates perhaps Dartmouth finally does have a role and a place in the heart of Indian Country, albeit one Eleazar Wheelock would neither recognize nor understand.

Colin Calloway is a professor of history and Native-American studies. He began teaching at Dartmouth in 1990. Excerpt from The Indian History of an American Institution: Native Americans and Dartmouth by Colin G. Calloway (Dartmouth College Press/University Press of New England, 2010).

Author Interview

Colin Calloway discusses his new book, The Indian History of an American Institution.

How does a Scotsman like you become an expert on Native-American history?

“I’m actually half Scottish and half English, so that makes me British. As someone interested in the history of this continent, I have always felt that the most compelling and distinctive aspect of American history was the presence of Indian peoples, whereas that presence was often slighted or ignored in U.S. history books. Much of America’s history makes no sense if you exclude Indians. In addition, British people were in contact with Native Americans for centuries and over most of the continent. In their dealings with the English, Highland Scots and Irish had similar colonial experiences to Indians.”

Why write this book now?

“President Jim Wright felt that the spate of incidents on campus targeting Native students in the fall of 2006 showed that Dartmouth needed to know its Indian history better. I never particularly wanted to write a book like this, but I saw it as a kind of service.”

In writing the book, what surprised you?

“I’m not sure it was a surprise, but what I most enjoyed was tracking the lives and experiences of the individual Native students who came here.”

What’s the future of Native Americans at Dartmouth?

“The trajectory since 1970 has, with various bumps and stumbles, been steadily upward. If the current administration sustains Dartmouth’s commitment to Indian education—and the indications are that it will—the future for Native Americans at Dartmouth should be bright, and that will be good for Dartmouth’s future as well.”