It’s what passes for good news in the modern era: In December the Obama administration announced that the $700 billion Wall Street bailout known as TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program) would cost $200 billion less than expected. That afternoon Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner ’83 told me, “You’re going to see there are substantial risk of losses still ahead although a fraction of what we initially estimated.” Hooray?

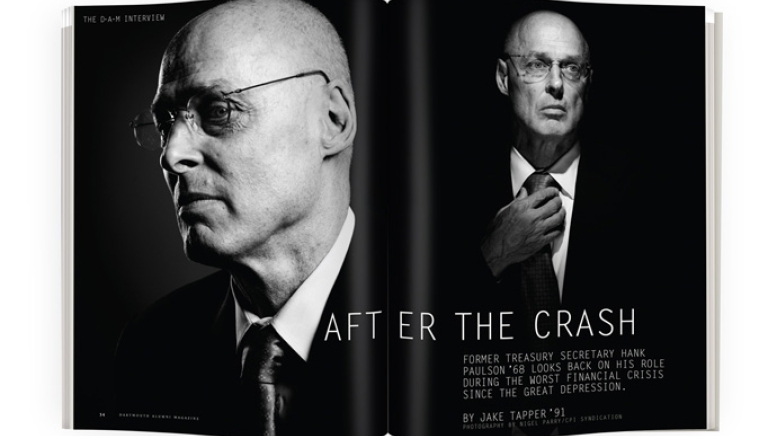

Earlier that day I had spent some time with Geithner’s predecessor, Henry M. “Hank” Paulson ’68, who led the charge for TARP, going so far as to comically get on his knees before congressional leaders to beg them to get a deal done. The bald, bespectacled Paulson is lean and energetic, with the pinky finger on his left hand mangled from a Dartmouth football injury. (As a senior he received the New England Football Coaches Award as Offensive Lineman of the Year; in 2000 he endowed the football coaching position in honor of his coach, Bob Blackman.) Geithner and Paulson follow in the footsteps of legendary Treasury Secretary and member of the Dartmouth class of 1826 Salmon P. Chase, who eventually became chief justice of the Supreme Court. It seems unlikely that either Geithner or Paulson will follow that path.

Having joined Goldman Sachs in 1974, where he amassed a fortune, Paulson left the financial organization where he was chairman and CEO in 2006 to become the 74th secretary of the Treasury. His was a stormy tenure—not because President George W. Bush lacked confidence in him, as had been the case with Paulson’s two predecessors Paul O’Neill and John Snow—but because of the financial meltdown that occurred on his watch.

We met on a chilly and bright December morning in his new office at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University in Washington, D.C., where Paulson is a distinguished visiting fellow, and where he was putting the finishing touches on his book, On the Brink: Inside the Race to Stop the Collapse of the Global Financial System, and working on what he calls his “passion,” environmental conservation.

Do you feel responsible for not having seen more indicators that a major economic collapse was coming?

When I came to Washington I thought there was a high likelihood there would be turmoil in the capital markets and I communicated that to the president and to [Federal Reserve Chair Ben] Bernanke and others. And although we worked to get prepared, I did not see the housing bubble as precipitating it, and then for a good while as it unfolded I underestimated the severity of the problem that was coming. But I also look at it and say that if I’d been omniscient we still couldn’t have got the powers we got any quicker. In other words, I started working on Fannie and Freddie reform from the day I arrived in Washington, and it took the impending failure of those two institutions to get the authorities [we needed at Treasury]. And with TARP, even in the height of the crisis it was difficult getting the powers that we needed.

Who’s to blame for the crisis?

There’s a lot to go around. One of the basic root causes that led to the excesses are the big global economic imbalances that have come with structural differences in the economy. Governments have been looking at these for a long time. The United States saves not nearly enough; it borrows too much. Other parts of the world save too much and don’t consume, so we have big, structural imbalances. [Others to blame include] obviously the financial institutions and their huge excesses; investors, in terms of not being disciplined and having enough diligence; the rating agencies; the government itself that came up with structures like we had for Fannie and Freddie; regulators who could have been more vigilant. It’s very difficult, if you want to be fair, to point the finger at any one group.

So you feel proud of the steps that you, as Treasury secretary, took to deal with the financial crisis?

I am very grateful that I was there, that during this collision of politics and markets—there couldn’t have been a worse time in terms of an election—we were able to navigate the minefields and do what needed to be done. There are a good number of things around the edges that I wish we’d done differently, but I think in terms of the major steps that were taken I’m proud of what was done. I think we avoided a major collapse of the system, which would have been really catastrophic.

When White House Chief of Staff Josh Bolten asked you to be Treasury secretary you pushed back. For a long time you didn’t want to do it. You even suggested somebody else’s name. Looking back today do you regret taking the job?

No, I don’t. It was an extraordinary time. It was very difficult. I am really pleased I had the opportunity because I think it made a difference. So I was glad I was Treasury secretary. And I’m really glad I’m not Treasury secretary anymore.

It was a position that President Bush had trouble filling to his satisfaction.

Right.

Your predecessors were not well regarded within the Bush administration. Do you now feel any sympathy for the O’Neills and Snows of the world?

It is very important to build strong relationships when you come to Washington. Starting with the president I had an understanding, but I knew that understanding would not be worth much if I didn’t build a relationship of trust with him. And I knew that was on me, not on the president. I had a career where even when I was running Goldman Sachs I was advising clients and principals, so I knew how to work with a principal, and I had an opportunity to build relationships with the president, with Ben Bernanke, with other Cabinet secretaries, with the leadership of the House and the Senate, people on both sides of the aisle. And I went right to work on that, and I think that paid big dividends when the crisis came.

Whom did you recommend for Treasury to Bolten?

I’m not going to say—and it’s not in my book.

You and the current Treasury secretary, Tim Geithner, have an excellent relationship?

Absolutely.

And you wanted him to be your deputy when you were at Treasury?

Right. But he had a very important job [at the New York Federal Reserve Board] and thought he could be more useful there. Still, we worked closely together.

You’re a Republican and he is a Democrat. Was that a difficult dynamic?

That was not an issue. That president had told me when I came to Washington that I’d be able to choose people for the key jobs at Treasury and that politics wasn’t going to be part of it. I actually didn’t know what Tim’s political party was.

Is the Treasury in good hands with him there?

I think it’s in excellent hands. Would I maybe have done some things differently? Of course, but I think what’s been done are logical extensions of what we did earlier, and my book On the Brink is—although it spends a lot of time on my thinking and the team at Treasury—more than anything else a story of teamwork and of three men—Ben, Tim and me—who complemented each other in terms of our skills and absolutely trusted each other and really worked very closely together on a crisis.

When you and Geitner first met and bonded was Dartmouth a part of that at all?

It was a very small part of it. I got to know him when he was president of the New York Fed, and we were working on issues and problems surrounding credit default swaps. And I just was very impressed with his intellect and his judgment and the way he tackled problems.

Do you think that there’s some reason the current and previous Treasury secretaries are Dartmouth graduates?

[Laughter] I think it’s interesting. You know, I love Dartmouth, and more broadly I love liberal arts colleges and universities in the United States. As someone who hired from all over the world when I ran a financial institution and, again, I know that we have problems in our secondary education, big problems in this country, but liberal arts education—where people are trained to question, to think, to express themselves orally, to express themselves in writing—is a great background. And I found that there’s just nothing like the students who come out of these colleges for a whole range of things.

Do you think there’s anything special, particularly, about Dartmouth?

Of course I do. I think Dartmouth is the largest and one of the very best institutions that’s focused primarily on undergraduate education. I had great faculty, got to know them personally, and it was just a very special school.

You ended up having a very good working relationship with Democrats in Congress, but my understanding is that the White House told you not to compromise on Fannie-Freddie legislation.

One of the first major tests that I had in my relationship with the president was in November of 2006, when I wanted to compromise with the Democratic side of the aisle…

...who had just won Congress.

Who’d just won, and there was a division of opinion. I took it to the president and he said, “This is why you’re here, Hank. You go work with them.” And our team worked out some agreements with Barney [Frank, chair of the House Financial Services Committee], and I believe those early agreements really set the stage for the success we ultimately had.

Is there anything that could have been done differently with Lehman Brothers, which filed for bankruptcy in September 2008?

We tried very hard, but we didn’t have the authority to put capital into Lehman Brothers until we got TARP. Even if the Fed could have found a legal way to make a loan, it would have been foolhardy because it would have been lending into a run—Lehman Brothers had a big capital hole and a liquidity problem, and we didn’t have a buyer for them as we did with Bear Stearns.

So there’s nothing that could have been done?

Yeah. We couldn’t find anything.

TARP certainly isn’t the most popular legislation in the United States. Do you think in retrospect there were not enough strings attached?

I could maybe phrase the question the other way around. When I went to Congress and sought those extraordinary powers that we needed, we ended up with various oversight bodies. We had the Governmental Accountability Office there permanently. We had the inspector general at Treasury. We had a new [U.S.] inspector general. We had a congressional oversight body. We had the financial stability oversight body. The number of strings attached was extraordinary.

I remember up at the Hill negotiating it and sitting around the table with a bunch of congressmen and senators and saying, “Who believes that we should have five different oversight bodies?” No one believed it, but everybody wanted their own. I think we got plenty of oversight and we got the flexibility we needed. Thank God we had the flexibility to put capital into the banks.

But when those AIG bonuses came out in early 2009 the American people were shocked that the same people who helped cause this horrible crisis were able to get these multi-million-dollar payoffs, some of which were coming from the taxpayer.

Right. You know, compensation was something we talked about very directly and negotiated with Congress. And I understood how politically sensitive it was, but the biggest concern we had was to have something that would work and would prevent the collapse of the system. And the balance we needed to strike was to say—and remember, we were looking at illiquid asset purchase programs—how do we come up with a set of restrictions and guidelines that allowed for broad participation by healthy institutions so they wouldn’t be stigmatized?

It was the same with the banks, because the way it tends to work in a crisis is every institution will say, “We don’t have a problem,” until they do, and then it comes very suddenly. In some ways it’s the tallest midget syndrome, you know, and they will shrink their balance sheets and hoard their capital. And so we needed a program that would let a maximum number of institutions participate. So I see the tradeoff.

The other side of the coin is with the banks. I believed there would have been up to 3,000 banks participating. But when that got stigmatized, we ended up with almost 700 banks participating, and we had banks withdraw. There were many banks that could have used this capital, and the country would be in better shape today if they had, but they pulled back. You see my point that there’s a tradeoff when you say, “Okay, here’s the program, and if you really need capital you’re going to come, but here are the restrictions that go with it.”

And executives make $200,000 a year, not $2 million.

Yeah, and then what you’ll do is you’ll have a program like some of the Europeans had that when a bank gets ready to fail, you can nationalize it or you can put in a lot of capital. We were trying to do something different. We were trying to design a program where you would get maximum participation. Now I understand the other side of that, I really do. With a couple of major institutions that have serious problems there’s a huge concern and a huge public concern, rightfully so, about compensation. But the sad facts are that if we stigmatize these institutions the people who will be hurt are the same people who are angry, because if you have an institution that can’t pay what it takes to keep the best people, the odds of paying the government back also decline.

As a Republican, how weird was it to see House Republicans sink that first TARP bill—and watch the market crash?

You know, we in this country don’t like bailouts, and thank God we don’t. I’ve looked at polls where 93 percent of the people opposed TARP and something over 60 percent were afraid of having something worse than a serious recession. So they never made the connection, and I never was successful in convincing people that this wasn’t being done for Wall Street and that there was really a connection between the banks collapsing and having serious problems on Main Street. So that just wasn’t done.

Was it your job to convince the nation?

Well, there are a lot of people who have tried. We have a president today who’s a pretty good communicator, yet I’m not sure the nation’s convinced on that topic. But we didn’t make that sale. I felt that what we were doing was putting aside policy principles in order to maintain the market system.

You are not a big “government intervention” guy.

No, but we needed to do it, because I so clearly saw the nature of the crisis. But it was otherworldly for me to be on the phone with congressman after congressman and have them lecture me about free market principles and then say to them, “But don’t you understand?” A lot of them did understand or they’d say to me, “Well, I’ll pray for you,” but they were going to vote the way they were going to vote. It’s a funny thing—the farther I get removed from this the more I look back positively; that it got done and Congress did act in an election year before the system collapsed. It was pretty extraordinary. At the time I wasn’t nearly as charitable in my own thinking. I just thought, “Can’t people see what’s happening?”

In Vanity Fair, you were quoted as saying you thought some of the questions asked at hearings were “idiotic.”

That’s right. It’s a good thing I didn’t say it there. There wasn’t much levity.

Is it true you got on your knees to beg Nancy Pelosi to get a deal done?

Yeah, that’s right. That was actually me trying to break a moment of tension because—well, one of the most bizarre events I ever participated in was the Cabinet meeting when the two presidential candidates came back [to Washington, D.C., at the end of September 2008, during the thick of the campaign].

It would have been easy for one of them to demagogue you.

One of the critically necessary ingredients was having both presidential candidates back TARP. One of the more interesting things my book shows is that I had regular communication with both of them. But based upon some of the things that were said on the campaign trail, I didn’t take it as a given that either presidential candidate was going be supporting it. And I didn’t take it as a given that when [GOP candidate Sen.] John McCain came back he was going to be supporting TARP.

Did you vote for McCain?

I tell a lot in my book, but that’s one thing I don’t disclose. I’ll say this: I was very grateful and I continue to be to both candidates for not attacking TARP, for being supportive, particularly near the end as McCain was falling behind. That was a gnawing worry on my mind the whole time. When I watched the presidential debates I did so with my heart in my throat.

There have been some nasty and personal attacks against you. It’s easy to say, “Well, it comes with the job,” but doesn’t it hurt sometimes?

Of course it hurts sometimes, and if this had taken place during any sort of a normal tenure at Treasury I would have been much more sensitive to it. But these were extraordinary times. And the attacks really didn’t come until I went to the Hill and said, “If we don’t get TARP, we’re going to be in a serious problem.”

What would have happened?

It would have been much worse. I understood why the American people were angry, and I viewed the attacks as a reflection of that anger. I’m also very mindful and very understanding of why people are angry, because there’s been tremendous destruction of wealth and economic pain and hardship. If we’d had one more institution go down there would have been a domino effect. To see double-digit unemployment today, with just Lehman going down and the financial system freezing, and for me to understand what would have happened if we’d had $3.5 trillion of money market funds blow up or some of the things that could have happened if we didn’t act—I am convinced we staved off absolute disaster.

If TARP hadn’t passed, would unemployment be even worse?

Just look at how difficult it is to repair the economy right now. When you’re in a period like this, I don’t care if it’s a small company or a big company, you have a CFO saying to the chief executive officer, “I’m not sure we’re going to be able to fund our working capital,” and, you know, working capital—there’s your payroll, your accounts receivable, your inventory. And so they all immediately start cutting inventory and then jobs and it is a very vicious cycle.

If AIG had gone down it would have been a multiple of the impact you saw with Lehman, and it would have taken down a good part of the rest of the financial system with it. The degree of concentration we have in our financial system, in my judgment, is a real problem. We have today 10 institutions that hold approximately 60 percent of the financial assets. In 1990 there were 10 that held about 10 percent. So you get a couple of these institutions going down and it’s a real problem.

Should there not be any organizations that are too big to fail?

Well they are as big as they are, so the key question is how do you regulate them and how do you have the proper authorities and tools in place so you can let them fail without taking down the rest of the system? This is something that Ben and I had talked with Congress about before Lehman went down. We saw we needed these powers. There’s no way we could get them, and the president and current Treasury secretary still haven’t gotten them. But I believe that with the right tools no institution needs to be too big to fail. You just need the power to unwind them outside of bankruptcy.

So you support the Obama administration’s push for new authorities?

We recommended it. It is, you know, our blueprint. I was recommending this in June of 2008.

What would you like to have done differently in your tenure?

Not send a three-page outline of the TARP legislation to Congress at midnight. You know, we should have done that at a press conference and explained what it was: a three-page outline. It wasn’t supposed to represent the complete request or something that was not to be changed. Congress had said, “Don’t give us a fait accompli,” but by sending it that way we made the legislative process more difficult.

Because it looked like a big power grab?

Yeah. I also wish I had been able to communicate more effectively and clearly why we needed to do what we needed to do and why this was not for the big banks but for the American people, and what the connection was between the need to rescue the banking system and how important that was for jobs and in people’s lives. At the time I was feeling very bad about it. But as I look back now I think the things we got wrong are primarily around the edges, and that the major things we got right.

Washington was a weird world for you to enter after a lifetime spent in the world of finance. There is a lot of posturing in this town. Did this surprise you?

No. I came to Washington in June of 1970. Right out of Dartmouth I worked for John Ehrlichman [counsel and assistant to the president for domestic affairs under President Richard Nixon]. I went to Harvard Business School, then I worked at the Pentagon and on the Lockheed Loan Guarantee. I went to the White House in April of 1972 and I left in December of 1973. So I was there during Watergate. Despite that, if I hadn’t been in Washington earlier, if I hadn’t walked over from the White House to meet with George Shultz when he was Treasury secretary, I would not have made the decision to come down and serve the country in July of 2006. My mom told me, and I don’t remember this, that when I left Washington I said to her, “I’m going to come back some day as Treasury secretary.”

Because George Shultz was somebody you respected?

Well yes, obviously, but I had worked on a lot of the economic and tax issues and I thought I’d gained a lot from my country and I didn’t want to look back when I was 70 and say I was asked to serve and had refused.

You were an offensive lineman at Dartmouth. What can you say about offensive linemen?

They have to eat dirt, you know. They labor in the trenches. And they’re good team players. I like to hire and work with people who’ve played on teams and competed, whether you were a good player or whatever. My Dartmouth football experience was a great one, and not just because we did well and won a lot of games. Many of the players who played with me have gone on to become doctors or lawyers. They’re outstanding professionals.

The pinky finger on your left hand looks mangled—is that a football injury from your Dartmouth days?

Yeah. I’ve forgotten which game, but on one play this finger went out this way. This other one, that way. The team doctor pulled them out, put some tape around them and sent me right back out there. When the swelling went down we could tell they were dislocated.

Do you keep up with the football team and Coach Teevens?

I don’t as much as I should. You know, I enjoyed my football experience at Dartmouth and I really, really appreciate it. I’d rather see Dartmouth win, but I’m not one of these guys that gets all obsessed with it.

You didn’t major in economics.

No. I was an English major and I was, as a matter of fact, going to go to Oxford and study English if it hadn’t been for the Vietnam War. I loved English. I planned to major in English and math, but after about my seventh or eighth math course I realized I wasn’t going to be a math major. I took several economics courses. They did not resonate with me. As a matter of fact, I didn’t particularly like them. I liked almost all my other courses and the professors.

Was there any class or professor at Dartmouth that you’ve carried with you and served as a source of comfort or inspiration during the crisis?

I had some really good experiences with professors. But there wasn’t one class that stands out. I wish I could say to you, “Boy, I thought back on microeconomics [during the financial crisis] and that was the answer.” Basically I found economists were pretty much worthless during this thing. Now, that’s an overstatement—Bernanke’s skill as an economist and practical skill and knowledge of economic history was incredibly valuable. But the economic models were worthless. The economist’s ability to predict what was going to happen when we were in the middle of a crisis was just…

Very few of them saw it coming.

Yeah.

Have you been following at all any of the College governance wars or lawsuits?

I don’t want to talk about it. I was very supportive of the Wright administration, and I support the new president. I’ve talked to him a couple of times on the phone and I’m very encouraged. I believe it’s a college that was very good when I got there and it’s continued to get better and better. So I’m not part of this group of people that is finding fault with the College. I just look at the product.

Were you in a fraternity?

Yes, SAE. But I didn’t spend a lot of time there, and I never lived there. It was more like a social club, and it was a positive experience, but my nickname was “The Phantom” because they didn’t see me a lot.

Why did you go to Dartmouth?

I thought I wanted to go east. I was recruited by Bob Blackman and I went up and visited. There was the Dartmouth Skiway—and I loved skiing. I like hiking and canoeing, and there was the Outing Club and fishing and all of those good things. I was very interested in having an undergraduate experience where I would have a close relationship with the faculty.

How did your daughter Amanda ’97 like Dartmouth?

She chose it because she likes the winter mountain climbing and all the Outing Club things and so on. Her friends were people that my son called “granolas,” you know, and she loved it and it was just a great experience for her.

Your faith is important to you. You’re a Christian Scientist.

Yes, you know, prayer has been consistently effective for physical healing and I’ve relied on it. That really didn’t enter into [the financial crisis]. It was much more praying for humility, to take ego out of it, praying for insight and judgment and wisdom—that’s where the faith and the religion was important.

You spoke to Vanity Fair writer Todd Purdum while you had a stomach virus…

Well, it wasn’t. He thought it was a stomach virus. I’ll say something: I didn’t miss a single day or an hour because of illness, and I worked around the clock for two and a half years.

What was it—nerves?

All my life, if I’m really exhausted—it doesn’t happen much—I will have dry heaves. When I was seeing Purdum I had been in Asia [for a quick trip]. I was working. I got off the plane at 2 in the morning. I was in the office a few hours later working and I just had a bout of the dry heaves.

When is our economy going to be back to where it was?

I’m not an economist. I just don’t know. I know the financial system is stable.

But the lending is not happening.

Yeah, for two reasons. There’s a demand side, okay. Then there are the financial institutions. You cannot go through what we’ve gone through with the amount of wealth destruction that has taken place with a reset that we’ve had on valuation with real estate, and when you look at the number of homes where the mortgages are worth more than the homes, it’s just going to take a good while to work through that. I think the trajectory is going to be positive. My view is very similar to what you’ve heard many economists state, that you’ll get GDP growth well ahead of employment growth. When you start to get employment growth, getting real wage growth is going to be tricky.

Do you think President Obama’s $787 billion stimulus package has been effective?

I haven’t really studied it to know. But, you know, I believe it has clearly had some impact.

You were at Goldman for quite some time. Do you look back at the behavior of some of your colleagues, competitors, other Wall Street titans with anger?

I’ve got to say that some of the things I witnessed and some of the problems I saw made me angry. The lack of controls, some of the risks that were taken; very, very sloppy behavior. I look back much more with sadness because, you know, I’m someone who believes in capital markets. They are responsible, to a large extent, for the fall of the Iron Curtain, for hundreds of millions of people coming out of poverty, for great advances in this country.

I look at it and I say, “How were we all part of this thing?” and I’m using a “we” broadly. First of all, we had a regulatory structure that hadn’t been changed dramatically since the Great Depression. Now that may be a bit of an overstatement, but I’ve got to tell you, it was a patchwork quilt, duplicative, unproductive—look at this growth of these complicated instruments, which led to excessive complexity. Like I said before, there’s a lot of blame to go around.

Your party is going through some sort of process right now—a rejiggering ?

Yeah, I would say that.

Tea partiers—not big fans of yours, those guys.

Yeah, to put it mildly. Appealing to populism, fear and hatred on either side of the aisle is something that disturbs me. I’m not that partisan and I very much respect people who are reasonable, who are moderate. When you have politicians who are not going to compromise on their principles it’s alarming, and you get divisiveness, not solutions.

Let’s touch on China. You feel strongly we need to be partners with the Chinese.

One of the things that I appreciate the most about my opportunity at Treasury was the opportunity to create the strategic economic dialogue. Anyone who knows me knows I’m not timid, and I think the Chinese appreciate strength. There’s not much that’s really difficult or important to get done in the world today that isn’t going to be much, much easier to get done if we can work with and reach common ground with China. And I believe the way to do that is through aggressive, robust engagement.

How do you want history to judge you?

I’ve always been proud of my character and the fact that I don’t leave anything in the tank. I give 100 percent. And I’ve also had a multifaceted career and I’ve done a fair amount in the conservation area, which is how I’m going to spend the next 10 years.

What might be the headline of your obituary?

“Was Treasury Secretary During the Biggest Financial Crisis Since the Great Depression and Worked with Ben Bernanke and Tim Geithner to Successfully Prevent a Collapse of the Financial System. Worked with Limited Tools to Prevent It.” Since I believe those are the facts I don’t see that as disputable by reasonable people who understood what was going on.

Jake Tapper is the senior White House correspondent for ABC News. He is a regular contributor to DAM.