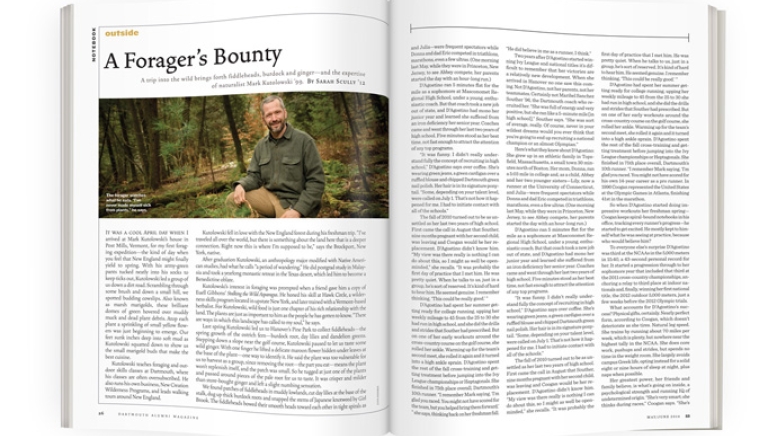

It was a cool April day when I arrived at Mark Kutolowski’s house in Post Mills, Vermont, for my first foraging expedition—the kind of day when you feel that New England might finally yield to spring. With his army-green pants tucked neatly into his socks to keep ticks out, Kutolowski led a group of us down a dirt road. Scrambling through some brush and down a small hill, we spotted budding cowslips. Also known as marsh marigolds, these brilliant domes of green hovered over muddy muck and dead plant debris. Atop each plant a sprinkling of small yellow flowers was just beginning to emerge. Our feet sunk inches deep into soft mud as Kutolowski squatted down to show us the small marigold buds that make the best cuisine.

Kutolowski teaches foraging and outdoor skills classes at Dartmouth, where his classes are often oversubscribed. He also runs his own business, New Creation Wilderness Programs, and leads walking tours around New England.

Kutolowski fell in love with the New England forest during his freshman trip. “I’ve traveled all over the world, but there is something about the land here that is a deeper connection. Right now this is where I’m supposed to be,” says the Brockport, New York, native.

After graduation Kutolowski, an anthropology major modified with Native American studies, had what he calls “a period of wandering.” He did postgrad study in Malaysia and took a yearlong monastic retreat in the Texas desert, which led him to become a Benedictine oblate.

Kutolowski’s interest in foraging was prompted when a friend gave him a copy of Euell Gibbons’ Stalking the Wild Asparagus. He honed his skill at Hawk Circle, a wilderness skills program located in upstate New York, and later trained with a Vermont-based herbalist. For Kutolowski, wild food is just one chapter of his rich relationship with the land. The plants are just as important to him as the people he has gotten to know. “There are ways in which this landscape has called to my soul,” he says.

Last spring Kutolowski led us to Hanover’s Pine Park to collect fiddleheads—the spring growth of the ostrich fern—burdock root, day lilies and dandelion greens. Stepping down a slope near the golf course, Kutolowski paused to let us taste some wild ginger. With one finger he lifted a delicate maroon flower hidden under leaves at the base of the plant—one way to identify it. He said the plant was too vulnerable for us to harvest as a group, since removing the root—the part you eat—means the plant won’t replenish itself, and the patch was small. So he tugged at just one of the plants and passed around pieces of the pale root for us to taste. It was crisper and milder than store-bought ginger and left a slight numbing sensation.

We found patches of fiddleheads in muddy lowlands, cut day lilies at the base of the stalk, dug up thick burdock roots and snapped the stems of Japanese knotweed by Girl Brook. The fiddleheads bowed their smooth heads toward each other in tight spirals as they prepared to unfurl while we wiggled free the burdock root stuck stubbornly in the ground.

After our foraging trip we headed to my kitchen, where pots steamed and sputtered as Kutolowski showed us how to prepare the wild foods. Knowing how to cook what you pick is as important as knowing what to pick. Fiddleheads, for example, can cause a stomachache unless they are boiled for at least 10 minutes. Other foods can be much more dangerous. Uncooked, prickly nettles will leave a rash on your skin. After boiling they’re edible—and delicious with butter.

Eating wild plants isn’t for everyone. A friend of mine picked the fiddleheads out of a fiddlehead-and-pesto pasta I cooked. Regardless, interest in wild foods has grown in the last decade, according to Kutolowski, which leads to a concern over too much foraging. “There are certain wild edibles, like Japanese knotweed or dandelions, that are invasive, that are everywhere,” he explains. “You can have people eat as many as they possibly want, and it’s not going do the land any harm. And then there are some things like wild leeks, which everybody wants when they get into wild foods. They can be easily over-harvested. I wouldn’t have worried about that eight years ago, because there just weren’t enough people involved. Right now there are so many it can be an issue.”

Another issue for foragers is knowing where to look for their bounty. When one woman in our group asked Kutolowski where he found a bucket of fiddleheads he brought to our dinner, he looked up slowly with a secretive smile and winked. He wasn’t about to tell.

Sarah Scully lives in Washington, D.C., where she works for Government Executive magazine.