“Are we having a midlife crisis?” I asked.

“Definitely,” replied Andy.

“Is this what we’re supposed to do?”

“That’s not clear to me.”

“It’s cheaper than a Ferrari or a divorce, right?”

“You’re not married.”

“I’m just saying.”

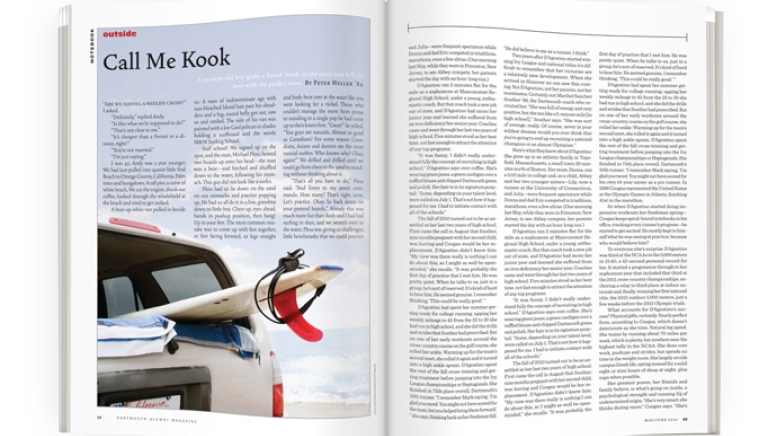

I was 45. Andy was a year younger. We had just pulled into quaint little Seal Beach in Orange County, California. Palm trees and bungalows. A tall pier, a curve of white beach. We cut the engine, drank our coffee, looked through the windshield at the beach and tried to get stoked.

A beat-up white van pulled in beside us. A man of indeterminate age with sun-bleached blond hair past his shoulders and a big, round belly got out, saw us and smiled. The side of his van was painted with a Joe Cool pelican in shades holding a surfboard and the words M&M Surfing School.

Surf school! We signed up on the spot, and the man, Michael Pless, heaved two boards up onto his head—the man was a bear—and hitched and shuffled down to the water, following his stomach. This guy did not look like a surfer.

Pless had us lie down on the sand on our stomachs and practice popping up. He had us all do it in a line, grandma down to little boy. Chest up, eyes ahead, hands in pushup position, then bang! Up to your feet. The most common mistake was to come up with feet together, or feet facing forward, or legs straight and body bent over at the waist like you were looking for a nickel. Those who couldn’t manage the move from prone to standing in a single pop he had come up to their knees first. “Great!” he yelled. “You guys are naturals. Almost as good as Canadians! For some reason Canadians, Asians and doctors are the most natural surfers. Who knows why? Okay, again!” We drilled and drilled until we could go from chest in the sand to standing without thinking about it.

“That’s all you have to do,” Pless said. “And listen to my seven commands. How many? That’s right, seven. Let’s practice. Okay, lie back down on your pretend boards.” Already this was much more fun than Andy and I had had surfing in days, and we weren’t even in the water. Pless was giving us challenges, little benchmarks that we could practice and attain. With each came a sense of accomplishment. His encouragement flowed in a constant, good-humored stream. Everybody was smiling. The seven commands were paddle forward, paddle back, slide forward, slide back, chest up, chest down, and stop. Then an eighth: You’re up! We practiced them in a line, lying in the sand, paddling air like beached turtles.

“Okay, everybody in the water! Don’t forget to watch out for people surfing in on your way out. And what did I say about your board? That’s right, never let your board get between you and the wave. You don’t want it getting shoved over you.”

I looked at the break. The pier was a hundred yards to our left and there were a couple of real surfers there, catching lefts just off the pilings. The waves were about waist-high and seemed gentle. Pless waded in to where he was chest-deep and motioned over a clutch of students.

“Okay, Mr. Peter, hop on your board. Here comes your wave.” I was on the board facing shore. He was standing, one hand on the waxed nose, facing the open ocean, studying the waves.

“Okay, scooch back, good, chest up, now—paddle!” I did. Then I felt a thrust of acceleration as Pless gave me a shove. I was matching the speed of the incoming wave. The swell came from behind and lifted me, I felt the nose tip forward, but I didn’t wipe out as I had for the past two days. Because Pless had positioned me back a bit on the board and my chest was up, the front didn’t dive and purl. I felt instead a rush of acceleration. The wave launched the board down the little face. Oh, man!

“You’re up!” Pless’ resonant shout cut through my reverie. I popped up. Instead of the weird crawl-and-stand I had been doing, now I popped up as we had just practiced. The board sped forward and—miracle!—I was standing.

Standing up on a rocketing surfboard.

My feet were apart, sideways to the board. Check. I was in a crouch, hands low. Check. I was speeding toward shore. Check. I was surfing! I saw green water at my feet. Then the wave broke around my knees and I rode the rough whitewater. I was frozen with amazement. I was yelling. I rode until the nose ground sand and the fins dug into the beach. A surge came behind and I toppled off into three inches of foamy water. I came up yelling, hands in the air. Did anybody see that? Oh, my God! That was so cool! The sense of speed! I am officially a surfer! Yay!

I was such a kook.

I was ecstatic.

The world no longer looked the same. Part of it must have been chemical, adrenaline and endorphins. While we were surfing a seal swam past the lineup and pelicans flew overhead. Gulls wheeled. The low swell rolled in from a bright sea and Catalina Island lay dark and blue on the horizon like a sleeping animal. And Pless’ encouragement and good cheer filled me with a rare magnanimity toward my fellow man.

Andy and I drove back to Main Street in Huntington Beach and headed for the Sugar Shack. We walked up the sidewalk crowded with spring-break tourists and young surfers carrying boards and I felt like a king. I belonged. All the surf kitsch—the surfboards in the windows of beachwear stores and hanging over the fronts of restaurants, the surf-scene prints on the shirts of the passing visitors—I saw it all and thought, Yeah, that’s the culture everybody wants to be a part of. My culture. ’Cuz I’m a surfer now.

You know what I did that afternoon? I bought a green rayon Hawaiian shirt with surfboards all over it.

And then I wore it. In public.

Timmy Turner was our waiter at the Sugar Shack and I was all excited and I tried to tell him about catching my first wave while he took our order. He flicked his eyes over me once and said, “Cool. Fruit salad or French fries?”

That night I called my girlfriend, Kim. I said I had discovered a new love—not a woman—and that it was the funnest thing I’d ever done aside from being in her company.

“That’s right,” she said. And added, “Get your butt home.”

Andy and I took five more days of lessons with Pless. On the third day I caught my own waves without being pushed. I felt like a natural. I had had to work really hard at everything I had ever done in my life, from kayaking to writing, just to get the rudimentary skills. But this seemed easy. I was taking to it like an otter. I loved catching waves and I loved getting tumbled. I loved the violence of the break and the stillness outside just sitting, waiting, watching the rolling swell all the way to the horizon and the absolute quiet that descended when I caught one and zipped into the beach.

Back on land all I could think about was when we would get back in the water. I was lit up. It was like a drug. I kept reliving the feeling of catching a wave. Andy and I walked into Huntington Surf & Sport to buy our own wetsuits. I really liked the idea of having my own. I got so excited talking to the sales manager about surfing that at one breathless pause he put his arm around my shoulder and said, “Son, if you were a little younger, I’d say, ‘There goes college.’ ”

Peter Heller lives in Denver. Adapted excerpt from Kook: What Surfing Taught Me About Love, Life, and Catching the Perfect Wave (Free Press, 2010), winner of the 2010 National Outdoor Book Award for Outdoor Literature.