Case Study

(CLICK HERE TO VIEW LARGER IMAGE)

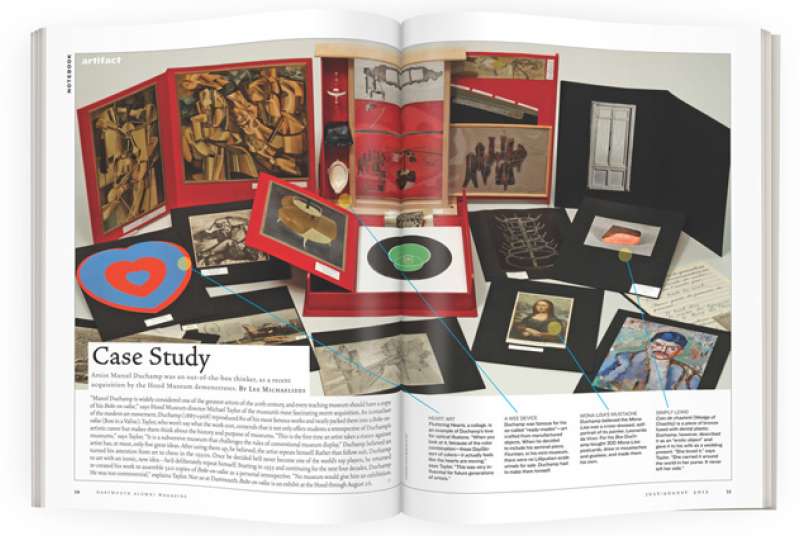

“Marcel Duchamp is widely considered one of the greatest artists of the 20th century, and every teaching museum should have a copy of his Boîte-en-valise,” says Hood Museum director Michael Taylor of the museum’s most fascinating recent acquisition. An iconoclast of the modern art movement, Duchamp (1887-1968) reproduced 80 of his most famous works and neatly packed them into a Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Valise). Taylor, who won’t say what the work cost, contends that it not only offers students a retrospective of Duchamp’s artistic career but makes them think about the history and purpose of museums. “This is the first time an artist takes a stance against museums,” says Taylor. “It is a subversive museum that challenges the rules of conventional museum display.” Duchamp believed an artist has, at most, only five great ideas. After using them up, he believed, the artist repeats himself. Rather than follow suit, Duchamp turned his attention from art to chess in the 1920s. Once he decided he’d never become one of the world’s top players, he returned to art with an ironic, new idea—he’d deliberately repeat himself. Starting in 1935 and continuing for the next four decades, Duchamp re-created his work to assemble 320 copies of Boîte-en-valise as a personal retrospective. “No museum would give him an exhibition. He was too controversial,” explains Taylor. Not so at Dartmouth. Boîte-en-valise is on exhibit at the Hood through August 26.

Heart Art

Fluttering Hearts, a collage, is an example of Duchamp’s love for optical illusions. “When you look at it, because of the color combination—those DayGlo-sort of colors—it actually feels like the hearts are moving,” says Taylor. “This was very influential for future generations of artists.”

A Wee Device

Duchamp was famous for his so-called “ready-mades”—art crafted from manufactured objects. When he decided to include his seminal piece, Fountain, in his mini-museum, there were no Lilliputian-scale urinals for sale. Duchamp had to make them himself.

Mona Lisa’s Mustache

Duchamp believed the Mona Lisa was a cross-dressed, self-portrait of its painter, Leonardo da Vinci. For his Box Duchamp bought 300 Mona Lisa postcards, drew in moustaches and goatees, and made them his own.

Simply Lewd

Coin de chasteté (Wedge of Chastity) is a piece of bronze fused with dental plastic. Duchamp, however, described it as an “erotic object” and gave it to his wife as a wedding present. “She loved it,” says Taylor. “She carried it around the world in her purse. It never left her side.”