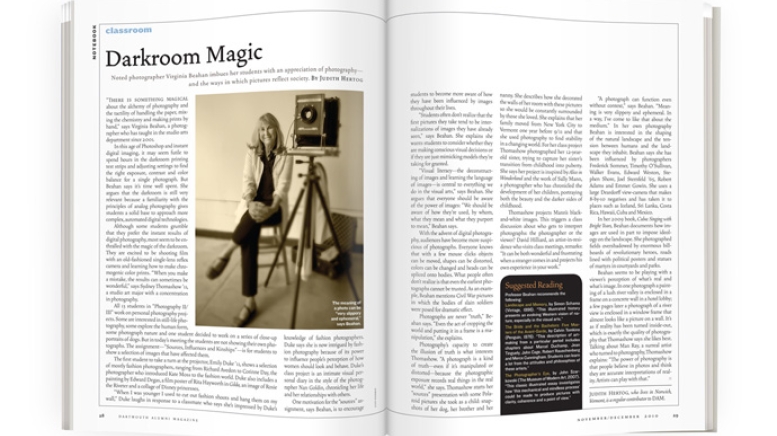

“There is something magical about the alchemy of photography and the tactility of handling the paper, mixing the chemistry and making prints by hand,” says Virginia Beahan, a photographer who has taught in the studio arts department since 2001.

In this age of Photoshop and instant digital imaging, it may seem futile to spend hours in the darkroom printing test strips and adjusting settings to find the right exposure, contrast and color balance for a single photograph. But Beahan says it’s time well spent. She argues that the darkroom is still very relevant because a familiarity with the principles of analog photography gives students a solid base to approach more complex, automated digital technologies.

Although some students grumble that they prefer the instant results of digital photography, most seem to be enthralled with the magic of the darkroom. They are excited to be shooting film with an old-fashioned single-lens reflex camera and learning how to make chromogenic color prints. “When you make a mistake, the results can sometimes be wonderful,” says Sydney Thomashow ’11, a studio art major with a concentration in photography.

All 13 students in “Photography II/III” work on personal photography projects. Some are interested in still-life photography, some explore the human form, some photograph nature and one student decided to work on a series of close-up portraits of dogs. But in today’s meeting the students are not showing their own photographs. The assignment—“Sources, Influences and Kinships”—is for students to show a selection of images that have affected them.

The first student to take a turn at the projector, Emily Duke ’11, shows a selection of mostly fashion photographers, ranging from Richard Avedon to Corinne Day, the photographer who introduced Kate Moss to the fashion world. Duke also includes a painting by Edward Degas, a film poster of Rita Hayworth in Gilda, an image of Rosie the Riveter and a collage of Disney princesses.

“When I was younger I used to cut out fashion shoots and hang them on my wall,” Duke laughs in response to a classmate who says she’s impressed by Duke’s knowledge of fashion photographers. Duke says she is now intrigued by fashion photography because of its power to influence people’s perception of how women should look and behave. Duke’s class project is an intimate visual personal diary in the style of the photographer Nan Goldin, chronicling her life and her relationships with others.

One motivation for the “sources” assignment, says Beahan, is to encourage students to become more aware of how they have been influenced by images throughout their lives.

“Students often don’t realize that the first pictures they take tend to be internalizations of images they have already seen,” says Beahan. She explains she wants students to consider whether they are making conscious visual decisions or if they are just mimicking models they’re taking for granted.

“Visual literacy—the deconstructing of images and learning the language of images—is central to everything we do in the visual arts,” says Beahan. She argues that everyone should be aware of the power of images: “We should be aware of how they’re used, by whom, what they mean and what they purport to mean,” Beahan says.

With the advent of digital photography, audiences have become more suspicious of photographs. Everyone knows that with a few mouse clicks objects can be moved, shapes can be distorted, colors can be changed and heads can be spliced onto bodies. What people often don’t realize is that even the earliest photographs cannot be trusted. As an example, Beahan mentions Civil War pictures in which the bodies of slain soldiers were posed for dramatic effect.

Photographs are never “truth,” Beahan says. “Even the act of cropping the world and putting it in a frame is a manipulation,” she explains.

Photography’s capacity to create the illusion of truth is what interests Thomashow. “A photograph is a kind of truth—even if it’s manipulated or distorted—because the photographic exposure records real things in the real world,” she says. Thomashow starts her “sources” presentation with some Polaroid pictures she took as a child: snapshots of her dog, her brother and her nanny. She describes how she decorated the walls of her room with these pictures so she would be constantly surrounded by those she loved. She explains that her family moved from New York City to Vermont one year before 9/11 and that she used photography to find stability in a changing world. For her class project Thomashow photographed her 12-year-old sister, trying to capture her sister’s transition from childhood into puberty. She says her project is inspired by Alice in Wonderland and the work of Sally Mann, a photographer who has chronicled the development of her children, portraying both the beauty and the darker sides of childhood.

Thomashow projects Mann’s black-and-white images. This triggers a class discussion about who gets to interpret photographs: the photographer or the viewer? David Hilliard, an artist-in-residence who visits class meetings, remarks: “It can be both wonderful and frustrating when a stranger comes in and projects his own experience in your work.”

“A photograph can function even without context,” says Beahan. “Meaning is very slippery and ephemeral. In a way, I’ve come to like that about the medium.” In her own photography Beahan is interested in the shaping of the natural landscape and the tension between humans and the landscape they inhabit. Beahan says she has been influenced by photographers Frederick Sommer, Timothy O’Sullivan, Walker Evans, Edward Weston, Stephen Shore, Joel Sternfeld ’65, Robert Adams and Emmet Gowin. She uses a large Deardorff view-camera that makes 8-by-10 negatives and has taken it to places such as Iceland, Sri Lanka, Costa Rica, Hawaii, Cuba and Mexico.

In her 2009 book, Cuba: Singing with Bright Tears, Beahan documents how images are used in part to impose ideology on the landscape. She photographed fields overshadowed by enormous billboards of revolutionary heroes, roads lined with political posters and statues of martyrs in courtyards and parks.

Beahan seems to be playing with a viewer’s perception of what’s real and what’s image. In one photograph a painting of a lush river valley is enclosed in a frame on a concrete wall in a hotel lobby; a few pages later a photograph of a river view is enclosed in a window frame that almost looks like a picture on a wall. It’s as if reality has been turned inside-out, which is exactly the quality of photography that Thomashow says she likes best. Talking about Man Ray, a surreal artist who turned to photography, Thomashow explains: “The power of photography is that people believe in photos and think they are accurate interpretations of reality. Artists can play with that.”

Suggested Reading

Professor Beahan recommends the following:

Landscape and Memory, by Simon Schama (Vintage, 1996). “This illustrated history presents an evolving Western vision of nature, especially in the visual arts.”

The Bride and the Bachelors: Five Masters of the Avant-Garde, by Calvin Tomkins (Penguin, 1976). “This description of art-making from a particular period includes chapters about Marcel Duchamp, Jean Tinguely, John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg and Merce Cunningham. Students can learn a lot from the attitudes and philosophies of these artists.”

The Photographer’s Eye, by John Szarkowski (The Museum of Modern Art, 2007). “This classic illustrated essay investigates how ‘this mechanical and mindless process’ could be made to produce pictures with clarity, coherence and a point of view.”

Judith Hertog, who lives in Norwich, Vermont, is a regular contributor to DAM.