A Burning Battle

Prologue

The People vs. the Pipeline

Nancy Sorrells sat down in the gallery of the Supreme Court of the United States, looked around the storied chamber, and took a moment to marvel at just how far she and her neighbors had come.

It was February 24, 2020. Nearly six years had passed since Dominion Energy, one of the biggest power companies in the country, had unveiled its plans to build a natural gas pipeline from West Virginia’s fracking fields across Virginia to eastern North Carolina. At 42 inches in diameter, the pipeline would be the largest to ever cross Appalachia’s rock-ribbed ridges. At close to 600 miles in length, it would be nearly as long as the Blue Ridge Mountains themselves. And with a price tag that had swelled to $8 billion, its owners would have a strong incentive to keep gas flowing through it for decades to come.

Sorrells, a publisher and historian who lived in a Shenandoah Valley hamlet a few miles from the project’s path, helped lead one of the dozens of grassroots groups that had banded together to fight it since 2014. She and a small contingent had traveled to Washington, DC, the night before, with plans to rise at three in the morning and wait for tickets to hear oral arguments in their case, Atlantic Coast Pipeline LLC and U.S. Forest Service v. Cowpasture River Preservation Association. But they discovered a long line of people already winding around First Street and East Capitol, angling to be among the fifty members of the public admitted.

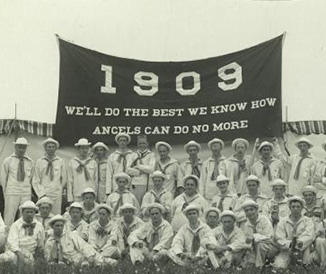

Throughout the night, fellow pipeline fighters from Virginia and West Virginia clustered together in small groups, chatting, sharing thermoses of tea, stamping their feet in the darkness. When Dominion routed its pipeline through their communities, the company had roused—and unified—a diverse group of citizens from across the political spectrum in opposition: retirees, innkeepers, farmers, scientists, physical therapists, pastors, nurses, teachers, builders, former lobbyists, engineers, and entrepreneurs. With temperatures hovering just above freezing, some wrapped themselves in sleeping bags and reclined on folding chairs to grab brief snatches of sleep. A member of Sorrells’s group stayed in line, while the rest retired for the night. At 5:00 a.m., having secured just one ticket between them, the group decided that Sorrells should be the one to use it. After all, few had been more relentless in the struggle against Dominion’s pipeline or more confident that they could defeat it.

For years, Sorrells had been telling everyone that the Atlantic Coast Pipeline was not inevitable—that, if they kept fighting, their band of Davids could overcome Dominion’s Goliath. In every email she sent, every flyer she handed out, she included the sentence: “This pipeline is not a done deal.”

And here, she thought, was the proof. Nearly everyone had expected Dominion—the most politically powerful company in Virginia—to steamroll them. “At the very beginning it was like we were just a little drop in the ocean,” she said. But after years of contending in courtrooms, street protests, shareholders’ meetings, newspaper opinion pages, and under the fluorescent lights at every conceivable kind of county or state or federal public hearing, they had stymied the largest fossil fuel pipeline project to come out of Appalachia.

And they had forced Dominion to appeal to the highest court in the land for permission to build its gas line through Virginia’s mountains.

Once the justices had taken their seats, Sorrells’s first thought was: There’s Ruth Bader Ginsburg, this is unreal. But as she listened to the oral arguments unfold, her excitement was tempered by a dawning realization: they were going to lose this case.

Many of the grassroots groups opposing Dominion’s pipeline were represented by the Southern Environmental Law Center, a nonprofit legal organization based in Charlottesville. As was common practice, SELC had hired a veteran counsel with experience before the Supreme Court to argue the case. As he jousted with the justices, Sorrells kept jotting down notes and thinking of points she wished he would make.

“It wasn’t a bad argument,” she said. “But he didn’t make those points, because he hadn’t lived it for six years.”

* * *

From her home at the western foot of the Blue Ridge, a few miles from where Dominion planned to drill a mile-long tunnel through the mountains, Sorrells had been living it since the day it was announced.

In the fall of 2014, Dominion had mailed a flyer to residents of communities along the project’s proposed route through western Virginia. Like a coach collecting opponents’ taunts on the locker room bulletin board to motivate her players, Sorrells had held on to it ever since. Printed in large font, against a backdrop of forested mountains and lush valleys stretching west of the Blue Ridge, was a bold claim: “The Atlantic Coast Pipeline will change everything. And nothing.”

This slogan encapsulated Dominion’s sales pitch: its gas conduit would supercharge collective prosperity, at virtually no cost. The company sought to convince everyone—local landowners, lawmakers, investors, regulators—that the ACP was essential to meet growing demand for gas, lower energy bills for its customers, and cut its own carbon emissions as it replaced older coal-burning power plants. And, moreover, that it could safely bury its pipe across the region’s steep, slide-prone slopes.

But for many who lived in its path, that tagline offered an inverted reflection of their darkest fears. They feared that, in terms of concrete economic benefits, the pipeline would change nothing. Local businesses wouldn’t be able to tap its gas even if they wanted to, unless they paid a $5.5 million connection fee. Construction jobs would be temporary, largely filled by crews from Oklahoma and Texas. Many local residents got their power from local cooperatives, not Dominion.

And on the other side, they worried the project really would change everything. That it would threaten life and limb, water quality, property values, local businesses, ecosystems, the very stability of their beloved mountains themselves, and their children’s ability to live safely among them. They worried about dwelling within the “blast radius” of a potential rupture and explosion. And many feared the climate consequences of a fossil fuel project with an eighty-year lifespan.

“The pipeline will be virtually invisible,” Dominion’s flyer promised. “There are 2.5 times more miles of underground natural gas pipelines than interstate highways in Virginia. Yet few people ever notice.”

Yet few people ever notice. Those five words were, in retrospect, an inadvertent Rosetta stone for understanding the gambit of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the broader narrative driving the gas building boom that had engulfed America for more than a decade. Dominion was just one of many energy companies making big bets on gas. The success of those investments depended on convincing people that there were few, if any, costs or risks worth paying any mind.

* * *

Excerpted from Gaslight: The Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the Fight for America’s Energy Future (Island Press, 2024) by Jonathan Mingle. © 2024 by Jonathan Mingle. Used with permission of the author. Gaslight won the 2025 Phillip D. Reed Environmental Writing Book Award and was a finalist for the 2025 New York Public Library’s Helen Bernstein Book Award for Excellence in Journalism.

Mingle, who lives in Vermont, is also the author of Fire and Ice: Soot, Solidarity and Survival on the Roof of the World (St. Martin’s Press). He currently is a McGraw Fellow at CUNY’s Craig Newmark School of Journalism.