Behind the Scenes at the Zoo

It’s a warm April morning at the San Antonio Zoo Animal Health Center, and a veterinary team is ministering to a Texas horned lizard under the guidance of Dr. Tarah Hadley, senior director of veterinary care. The lizard has a mass on its foreleg, and Hadley has just done an x-ray. The image outlines the tiny hand, two bony knuckles slightly askew. Emily Dickson, a vet-school student on a monthlong internship, asks whether it’s an abscess. “Yes, but he walks on that hand, so I’d rather not cut it open if I don’t have to,” Hadley says. “We can do a less invasive treatment, and if it doesn’t resolve, then we take the next step.” The lizard squirms wildly. “I know, buddy,” Hadley murmurs. She orders pain meds and an antibiotic.

“Okay,” she says to her team. “What’s next?”

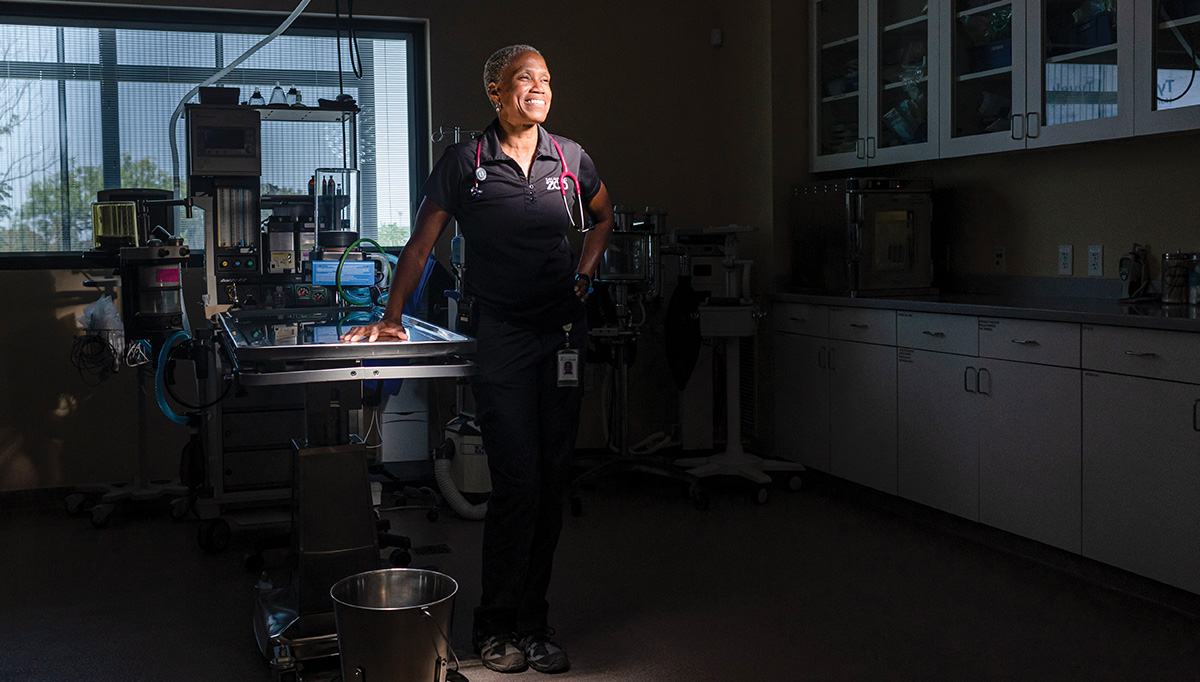

At 56, Hadley is energetic, with a quick smile and air of softspoken enthusiasm. Dressed in cargo pants, fleece, and running shoes, she looks ready for the nonstop whirlwind that is a zoo vet chief’s day. As the first woman and African American to hold the post in the 110-year history of the San Antonio Zoo—in a profession where only about 1 percent of practitioners are Black—Hadley loves a challenge. At a zoo that hosts more than 750 animal species on its 50 bustling acres, she gets plenty of them. In the hall outside the procedure room a whiteboard lists the day’s cases: “Rhino Blood Draws,” “Crayfish Exit Exam,” “THL Semen Collection.” Texas horned lizard semen collection? How do you even do that?

“Not very easily!” she says, laughing.

Becoming a veterinarian was not what someone might have predicted for a Black girl growing up in the 1970s in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood. Hadley was born to a teenage single mother, and the family’s resources were limited. Drawn to animals from an early age, she frequented the Franklin Park Zoo and the New England Aquarium. Her cousin recently sent a photo of her at age 6, standing at the aquarium’s touch tank. “In the picture I look completely entranced. My cousin said he remembers how the keeper was asking questions and I was answering all of them.”

When Hadley was 8, her family relocated to Georgia, then later to Virginia. The settings inspired a reverence for nature in the girl who loved nothing more than to tramp through the Georgia woods and creeks in search of crayfish. In Virginia she lived near the George Washington Parkway and its walkways, which traverse wetlands and riverbanks. “I would take my bike and ride for miles, out into the bogs and cattails. I was a huge explorer.”

At Dartmouth she majored in English, spurred by an abiding dream to write children’s books. After graduation she worked as a news aide at The Washington Post, then as a reporter for the Press of Atlantic City, moving to New Jersey with her husband and classmate, Rakeim Hadley ’91. There, she volunteered at the Cape May County Zoo—“shoveling llama and pig poop”—and joined birding groups in a nearby wildlife refuge. After a couple of years Hadley began to worry that journalism wasn’t an ideal fit and confided her doubts to Rakeim. “One day out of the blue he says, ‘Did you ever think about being a veterinarian?’ And it was like, Ding! I had never been around a vet, but somehow it just was right.” Hadley found part-time work at an animal clinic while attending a local community college to get prerequisites for vet school. Two years later she was accepted at Tufts.

Another piece of her career puzzle fell into place when she met a couple trying to adopt out an exotic bird, a lilac-crowned amazon named Chichi. On a whim, she offered to take it. “As soon as I got that bird, I knew I wanted to work on these animals. It was like a second epiphany.” At a bird conference she met Dr. Michael Jones, the first board-certified Black avian veterinarian in the United States. Jones mentioned a residency in avian medicine he oversaw at the University of Tennessee. Three years later, when Hadley graduated from Tufts, she applied and was accepted.

The residency required her to spend one-third of her time at the zoo in Knoxville, Tennessee. “We call it the avian/tiger residency,” says Cheryl Greenacre, a University of Tennessee veterinary professor who became a mentor. “Tarah focused on birds, but she also got exactly the kind of broad exposure you need for zoo medicine.” Hadley recalls the residency with amazement. “Here I am, the avian person who’s also doing surgeries on turtles and chimpanzees and tigers. And lions—lots of lions!”

A zoo veterinarian’s day begins early. By 6:30 a.m. Hadley is at the computer in her small office to input notes about a hernia repair she did on a yellow-backed duiker antelope a day earlier. She’d never operated on one before but had done the procedure on cows and was able to extrapolate. “A lot of this job is MacGyvering,” she says. “You have to figure it out.”

From her office it’s a short walk to the health center, where rooms are crammed with ultrasounds and x-rays, fridges, microscopes, and respiratory machines. Cupboards bear labels such as “Rodent Dental” and “Amphibian Anesthesia.” Black cases contain dart pistols and rifles used to anesthetize animals difficult to inject manually—and in case of an escape. A few years back a young gibbon got out of its habitat, Hadley recounts. “She was exploring, just being curious, and she found a defect in the fence. We had to clear people out as a precaution.” They were able to get the baby ape back, she says, “before the mom had a conniption.”

The day’s action begins with the lizard’s foreleg procedure. After that herpetologist Tanner Easton brings in a venomous snake, its head and upper body snugged into a plastic protective tube. A European long-nosed viper, it was sent to the zoo for breeding. “It didn’t work, and we’re sending him back,” Hadley explains. Easton briefs the team on the snake’s condition, its rough skin and patchy shedding. An x-ray reveals that the snake’s spine is a bit gnarled, possibly due to trauma or osteomyelitis, Hadley observes, which could explain the failure to mate. “Or maybe they just didn’t hit it off,” Easton quips.

Reptile procedures done, Hadley zips down to the zoo, where the kiddie park is celebrating its 100th anniversary. Then it’s back up the hill to attend an avian pathology meeting, where a colleague analyzes the last three years of bird deaths at the zoo. Noon finds Hadley in her office, typing up notes while downing a quick nosh of yogurt and muesli.

Being veterinary director of a large zoo requires Hadley to maintain a tricky balance between providing healthcare and dealing with myriad administrative tasks, even as she engages the zoo’s larger mission of securing a future for wildlife. There is a lot to do and a lot to ponder. For example, a cryogenic deepfreeze in the necropsy building stores tissue samples from various animals. “We had samples of our elephants here,” Hadley says. “Colossal has them now.” That’s Colossal Biosciences, a company attempting to “de-extinct” the woolly mammoth by genetically re-engineering Asian elephants. Hadley says it would be cool to see a live mammoth but stresses the need to consider the genetic ramifications. “And maybe we should put more effort into saving species that are disappearing right now than in trying to recreate something that’s already gone.”

At 1 p.m. Hadley hurries back to the health center for the lizard semen collection she had joked about earlier. The patient is named Seymour, and, as with the viper, his keepers have been trying to breed him. It hasn’t happened, and the hope is that semen analysis will reveal why. First, however, they need to get the sample. Hadley injects Seymour with a sedative, and the team tries different techniques, rubbing and pressing the lizard’s abdomen, even stroking it with a toothbrush. They try repeatedly, but nothing works. “Well, did you get it?” Hadley’s assistant Roxanne Frias asks as she enters the room. “Nope,” Hadley replies. Everyone groans.

Asked what she loves most about her job, Hadley says it’s getting to know her coworkers and not just in the vet department. “It really helps me tap into what’s going on around the zoo,” she says. She relishes her work, its ceaseless churn of new challenges, and the frequent improvisations it demands.

Her penchant for thinking on the fly proved crucial in February 2021, when a winter storm overwhelmed the Texas power grid and most of the zoo lost power, placing its denizens at risk of freezing. The tropical flamingos were among the most threatened. Where to put them? Stymied, Hadley walked to the middle of the snow-covered zoo grounds. “I stood there and basically just swiveled around and looked. And then I thought, aha, the Riverview Restaurant has power!” She and staff cleared out the tables and chairs and ushered 100-plus flamingos into the empty dining room.

Hadley and her colleagues managed to relocate every animal in the zoo that needed it—and when power was restored five days later, not a single one had perished. “Tarah is always willing to get in the trenches,” says zoo president and CEO Tim Morrow, praising her steadfast leadership during the crisis. “We didn’t have a full staff on hand, pipes were bursting, we had to get these animals inside. Dr. Tarah was the person saying, ‘We can do this!’ Being that calming voice of veterinary care was crucial for the staff.”

The same can-do spirit informs her teaching. Hadley stresses to her students that it’s okay to make mistakes. “I’ve had a lot of stumbles along the way,” she says. “It’s important for anyone pursuing this career to know that they can pick themselves up and keep moving forward.” To that she adds the crucial importance of enjoying the process. “I want students to learn what they need to learn,” she says, “but I want them to feel they had fun doing it.”

At 6 p.m. Hadley exchanges her cargo pants for dress pants, her running shoes for high heels, and heads to the Africa Live! habitat for a donor event. It’s a perfect setting for a zoo fundraiser, a subterranean grotto with a floor-to-ceiling window facing an underwater habitat where two hippos lazily swim and frolic. Morrow gives an update on coming developments at the zoo—a coral lab, a new event center, and Congo Falls, the enormous new primate habitat set to open in November with at least eight gorillas.

He invites Hadley and Rachel Malstaff, director of mammals, to discuss their work. As they prepare to speak, one of the hippos aims its hindquarters at the viewing window and emits an explosive cloud of poop. The audience guffaws.

“He’s marking his territory,” Malstaff says with a grin. “He wants us out!”

For a half-hour they field questions on conservation projects, habitat safety, and favorite animals. “Capybaras,” Hadley says. “They’re my buddies.” Someone asks about the weirdest thing she does in her job, and she recounts the lizard semen collection earlier in the day. It’s yet another facet of her job Hadley manages with skill, genially charming the donors, deftly mentioning that an endoscopy machine her team used a day earlier was a donor contribution. “Tarah just has terrific rapport with everyone,” Morrow says, “with the keepers, with people like me who are not animal care experts, with donors and board members. She has an incredible ability to connect with people.”

After their talk, she’s still at it, sticking around to chat about capybaras with a beaming 8-year-old and her mom. By the time the room empties it’s 8 p.m. Sometimes after a 14-hour day like this, it can be hard to unwind. “I’m thinking about my staff, I’m thinking about the animals and how this or that problem will turn out,” Hadley says.

Yet she clearly delights in the Noah’s Ark of creatures under her care. Watch her talk with an eager child about capybaras and you can see the curious girl who answered all the keeper’s questions decades ago and discovered via animals and nature a powerful thirst for knowledge. That thirst is something Hadley keeps front and center when she thinks about her mission at the zoo. “We’re in the digital age and there are a lot of competing interests for kids,” she notes. “But my hope is that if somebody gets the exposure that I had as a child, maybe years later they’ll remember coming here and they’ll know, ‘Yeah, this is something I want to get involved with in my life.’ ”

Underlying it all remains a deep-seated sense of wonder at the animal world. “Has anybody stopped to think about the fact that birds can fly?” she muses. “I mean, we see it every day and we take it for granted, but they’re flying!” If she could come back as an animal in her next life, she says, it would be as a bird. Hadley grins and adds a sheepish disclosure: She’s afraid of heights. “We live on the 24th floor and we have a balcony. I love sitting out there but when you lean over, it’s like, ugh.”

It’s an awkward thing for a bird doctor, Hadley admits. But she’s confident she’ll overcome it in her next life—when she returns with wings.

Rand Richards Cooper, a frequent contributor to DAM, most recently wrote “Six Hundred Thousand Despots” for the January/February issue.