Legal Hurdles

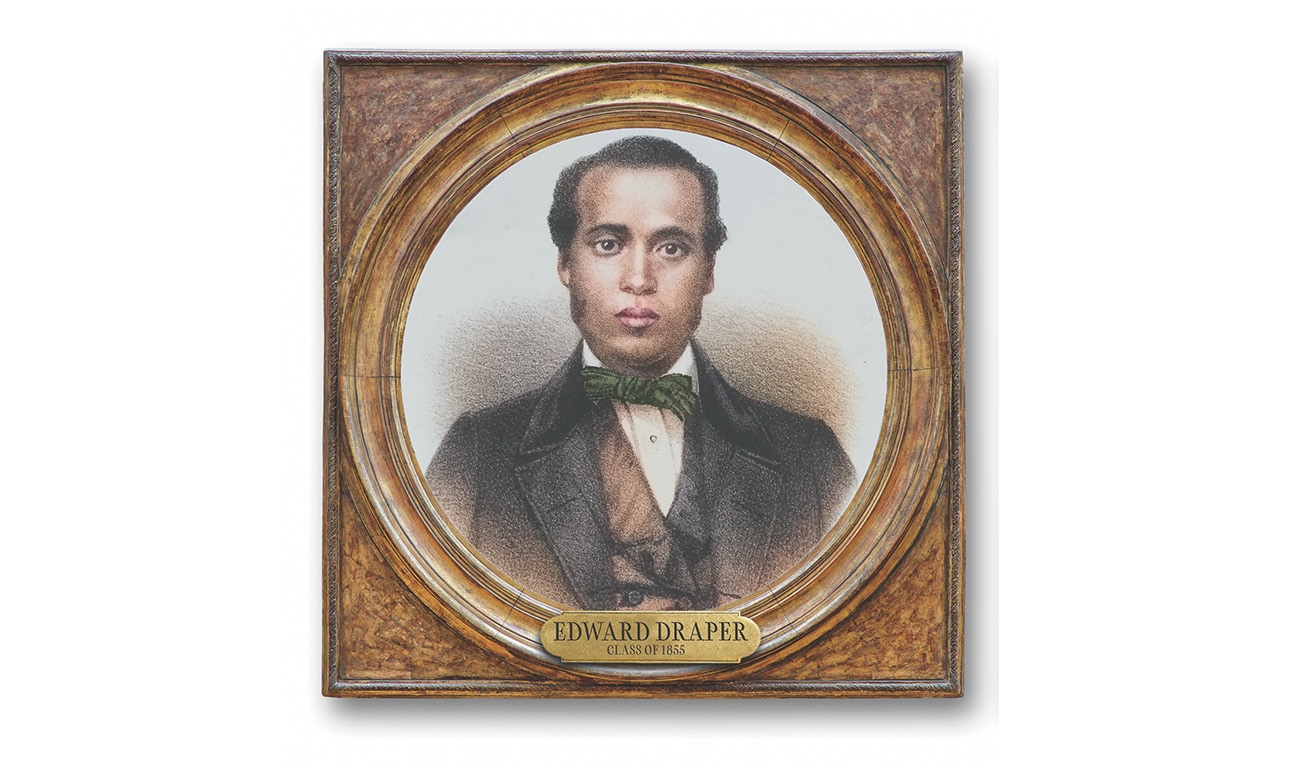

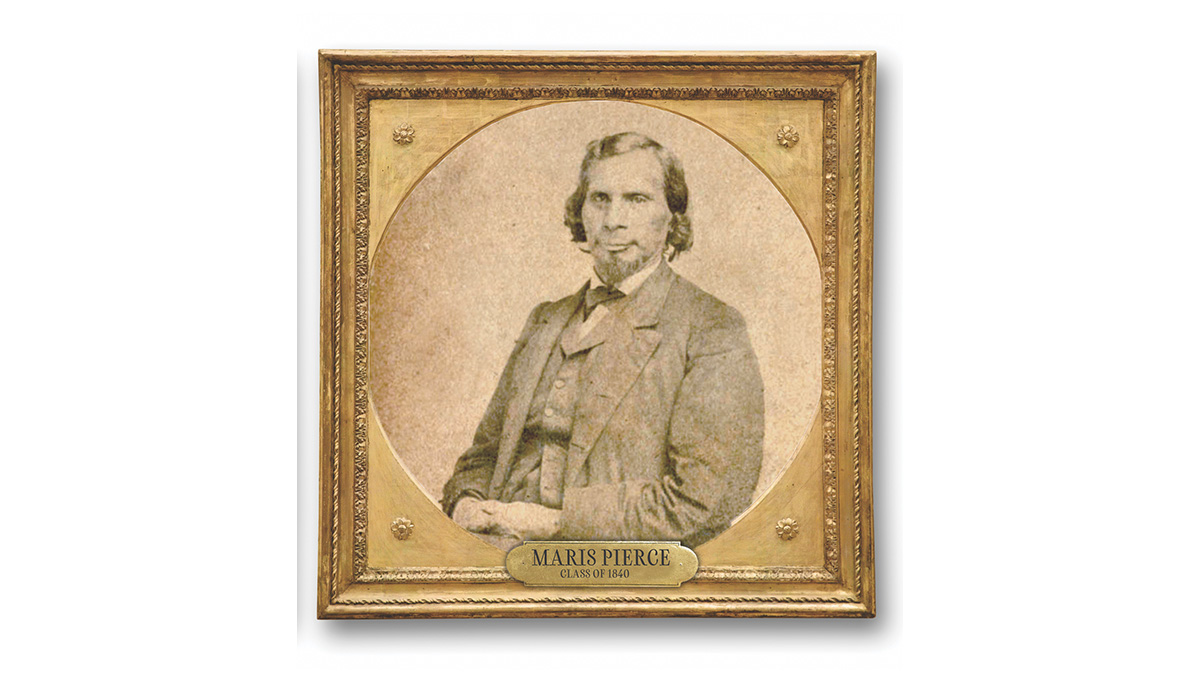

First in their families to attend college, the men rose to earn Ivy League diplomas, achieve careers as lawyers, and participate in major historic moments amid tremendous social change. Despite their groundbreaking accomplishments, two mid-19th-century alumni—Maris Pierce, class of 1840, and Edward Draper, class of 1855—could not gain acceptance to the bar. The whites-only restrictions of the time officially excluded Draper, a Black man, and Pierce, a Native American, from practicing in Maryland and New York, respectively.

Some civil rights-minded attorneys contend that Draper, Pierce, and other minority lawyers should win posthumous admission to their states’ bars, which has prompted newfound appreciation for the men and their work. “They deserve to be part of the same profession that I am,” says John Browning, a longtime civil litigator and former Texas appellate court justice turned law professor who advocates for bar acceptance for previously denied minority lawyers.

Accelerated by the racial reckoning that followed George Floyd’s 2020 murder, Browning’s advocacy recently notched a big win. In a rare, long-after-the-fact move, the Maryland Supreme Court admitted Draper to that state’s bar in 2023, 166 years after Draper sought admission. Browning, who is white, hopes to achieve similar recognition for Pierce soon. “This is not a DEI issue or about giving anybody special treatment,” he says. “It’s about giving recognition deserved a long time ago.”

Born in 1834 in Baltimore, Draper was the son of Garrison and Charlotte Draper, free Blacks in a pre-Civil War border state where about half of the Black population was still enslaved. A tobacconist in a state that banned even free Blacks from selling tobacco, beef, and wheat without special permission, Garrison Draper rued the nation’s racial double standards. He ultimately threw his support behind free Blacks relocating en masse to Africa to colonize what would become Liberia to “transmit the blessings of civil and religious liberty.”

Meanwhile, he enrolled his teenage son in a desegregated public school in Philadelphia, where Edward studied Latin, Greek, and math. Among the first Black students to set foot in Hanover when he arrived in 1851, Edward Draper thrived in his first year, enjoying an exam average of 1.8 out of 5, with 1 being the highest, based on research by former University of Maryland law professor David Bogen. Though Draper’s grades—and chapel attendance—slipped a bit later, mistreatment by professors may have been a factor. “We would both give three groans for, and bury in oblivion, that insignificant body of weak-minded men called the faculty,” he wrote in the yearbook of classmate Silas Hardy. “Yet do not forget the class and especially your friend.” Draper graduated in four years, the first Black person from Maryland to complete college and become a lawyer.

Afterwards Draper took jobs “reading law”—then the equivalent of law school—alongside prominent Boston-based abolitionist Charles Storey, whose mentor George Curtis represented the slave Dred Scott in the infamous U.S. Supreme Court race case. In the court’s 1857 decision, which went against Scott, free Blacks were found to have no legal rights, which likely fueled the Drapers’ ideas about leaving the United States.

Edward Draper forged ahead, petitioning a Baltimore judge later that year to join the bar. But Judge Zaccheus Collins Lee, a slave owner and cousin of the soon-to-be Confederate leader Robert E. Lee, denied his attempt on strict legal grounds. Draper would be “qualified in all respects to be admitted to the bar in Maryland, if he was a free white citizen,” wrote Lee, who added that he endorsed “his establishment and success in Liberia.”

Within weeks of Lee’s rejection, Draper and his wife, Jane Jordan, set out for Monrovia, Liberia, on a promising sea voyage. “Our cabin fare is good,” he wrote to his father, with “things which I know you have not, such as green corn, fresh tomatoes.”

Although Draper was finally in a place that allowed him a career, he would enjoy it for only a few months, dying of tuberculosis in Liberia’s Maryland County after about a year. He was 24.

More than a century and a half later, at Draper’s swearing-in ceremony, pro bono lawyer Domonique Flowers, who worked with Browning to give Draper his due, took the legal oath on Draper’s behalf. “I was overwhelmed,” Flowers says. “But though I may have stood in his stead, I could never really have filled Draper’s shoes.”

Like Draper, Maris Pierce, a member of western New York’s Seneca tribe born in 1811, had a family that straddled starkly different worlds.

Distrust of European settlers was running high among Senecas in the early 19th century, after land grabs by speculators dramatically whittled their territory. The tribe had lost millions of acres in a sweeping 1797 agreement with Dutch investors and American developers, and in 1826 the Holland Land Co. gobbled up six of the 10 Seneca reservations remaining in a deal that was never officially ratified. But Pierce’s father, John Pierce, a Seneca chief who took his English name from a visiting missionary, pushed to have Quakers set up schools on tribal lands and voiced his support for them in a letter to President James Monroe.

Maris Pierce, also known as Hadya-nodoh for “swift runner,” bounced between off-reservation grade schools, including Vermont’s Thetford Academy, before enrolling at Dartmouth in 1836 at 25. While far older than his fellow students, he shared their religious views: A year earlier Pierce had converted to Presbyterianism, a common choice among Native Americans who had their tuitions paid for by the Presbyterian-rooted Scottish Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge. Another blow against the tribe came during Pierce’s third year at Dartmouth, when Seneca chiefs agreed to surrender their last four parcels, including the one along the Allegheny River where Pierce grew up, and relocate the entire tribe to Kansas. Pierce frequently journeyed from campus to help with tribal legal issues, and though he was a signer of that 1838 deal, he later turned against it, accusing white negotiators of bribing Seneca chiefs and generally cheating the continent’s “aboriginal inhabitants.”

“It has been said and reiterated so frequently as to have obtained the familiarity of household words, that it is the doom of the Indian to disappear, to vanish like the morning dew,” he said in a fiery 1839 speech at a Buffalo, New York, Baptist church that echoed others he gave to white audiences in Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. But, he thundered, “Why must we be crushed by the arm of civilization?”

Pierce’s ease among the rich and powerful may have impressed tribal elders. Even before he graduated in 1840, they named him one of the four attorneys to advocate for the tribe in Washington.

After college Pierce, who married the daughter of a British army officer, buried himself in law books for two years at a Buffalo firm, according to Dartmouth history professor Colin Calloway.

Whether Pierce ever tried to convince a judge he was worthy of bar acceptance is unclear, but the lack of membership didn’t hobble his career. In 1842 Pierce’s negotiations with federal officials led to the Third Treaty of Buffalo Creek, a major revision of the unpopular 1838 agreement. It allowed the Senecas to retain most ancestral lands and stay in New York.

Pierce also orchestrated his tribe’s 1838 switch from a hereditary system of government to the elections-based version that allowed the creation of the Seneca Nation, which to this day occupies the land Pierce helped save. A resident of his own reservation for his final decades, Pierce died in 1874 at 63.

Browning believes elevating Pierce and Draper could turn them into role models for aspiring attorneys. “It’s tough when you’re a young person and don’t see anybody who looks like you,” says Browning, whose Irish Catholic childhood home in New Jersey prominently featured a photo of President John F. Kennedy. “It’s important to see one of your own up there.”

C.J. Hughes is a longtime contributor and a member of DAM’s editorial board.