In the Face of Depression

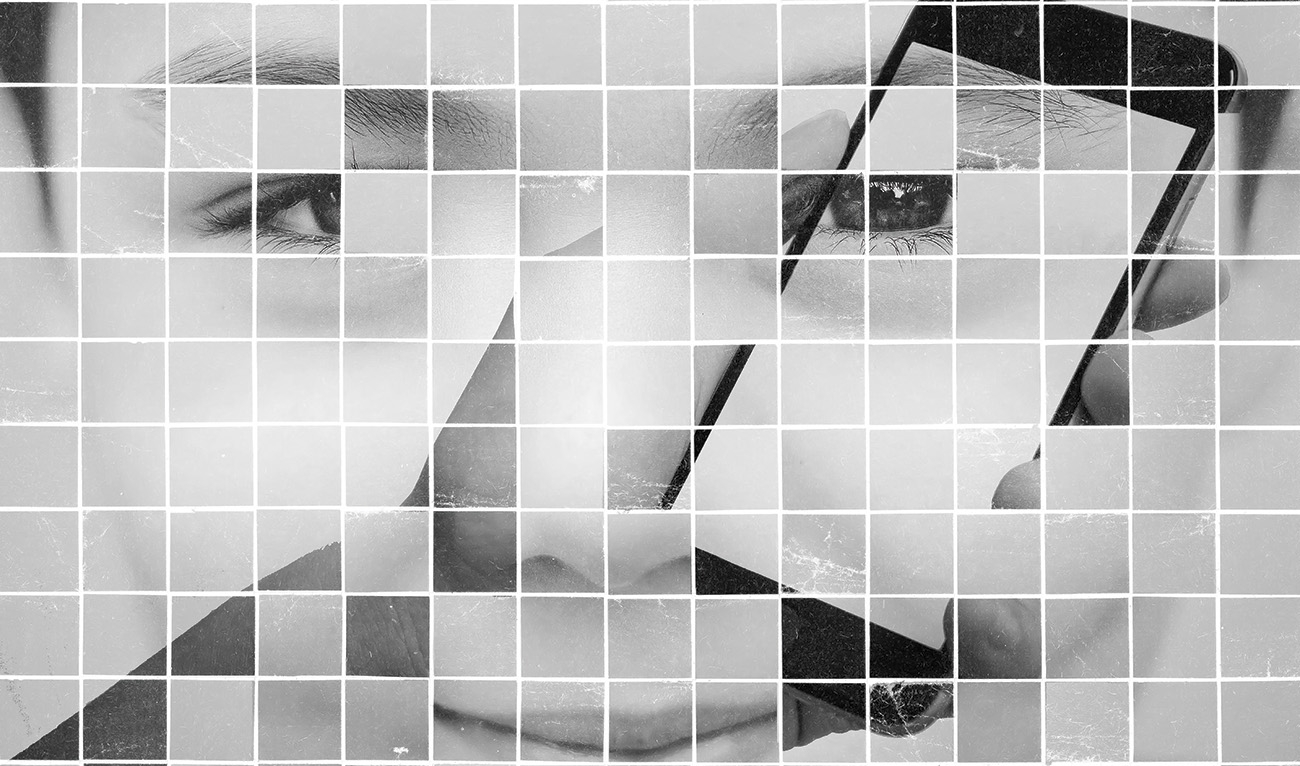

For years Andrew Campbell had wanted to build an app that could detect depression. But smartphone cameras just weren’t good enough. “The original front-facing camera was really crappy in 2013,” he says. “Fast-forward to 2023 and things had changed a lot.”

Campbell, a computer science professor who works at the nexus of technology and mental health, wasn’t thinking of what the improved cameras could do for Instagram influencers. He realized the selfie camera’s improved resolution was now good enough for what he envisioned.

The app Campbell and his team of researchers recently built, called MoodCapture, is designed to spot signs of depression from selfies. In a study of its effectiveness, participants recruited from around the country who already were diagnosed with major depressive disorder installed the app on their phones and responded three times a day to an eight-question survey that asked about their symptoms while the app simultaneously took a burst of five photos.

The accuracy rate of MoodCapture—gauged by cross-checking the selfie analysis against the survey—was around 80 percent but should rise as the algorithm is refined, according to Campbell. “It probably needs to be 90 percent or 95 percent before you would want to tell somebody, ‘Hey, you look like you’re at heightened risk,’” he says. “Then the intervention is very dependent on the person. It could be, go speak to a good friend or a parent or go for a run.”

The app scans each image broadly, including background details, rather than focusing only on facial features. “The ambient environment and lighting conditions in folks’ daily lives that we’re also capturing is affecting these predictions,” says Nicholas Jacobson, assistant professor of biomedical data science and psychiatry and one of the study’s authors. “The holistic analysis performed very well.”

MoodCapture is just the most recent smartphone-related tool aimed at addressing mental health concerns that Campbell—now regarded as a worldwide leader in the field—has developed over the past two decades with researchers in the two Dartmouth labs he runs.

Back in 2005, when he was about to begin teaching at Dartmouth after a decade at Columbia, Campbell received an intriguing call from Nokia. “Come visit us in Finland,” the representative said, “and have a look at what our new phone can do.” It was the pre-smartphone era, and at that point Nokia was a top mobile phone maker. Campbell, an expert in mobile sensing, readily agreed.

At the meeting, Nokia unveiled a phone that, among other things, had a gyroscopic sensor built in, so that if you turned the phone sideways the screen automatically rotated to remain vertical. Simple, but with the release of the iPhone still a year away, it seemed new. “The sensor was there to drive the display,” Campbell says. “But a light went on in my head. I realized the sensor could tell us about the behavioral activity of the user. It was like a moment in your life when you put it all together. I switched fields and pivoted to it as soon as I got to Dartmouth.”

In 2006, Campbell and his team created CenceMe, an app that used the built-in GPS and accelerometer sensors in phones to pull together information about the user’s location, movement, and activities, so the user could share that information on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. It was the first app of its kind to hit the Apple App Store when it opened in 2008.

Today, every smartphone on the planet has functions that emulate Campbell’s innovation, and apps—from exercise trackers to social media platforms—depend on them. “We were the first group to put a machine-learning algorithm on the phone, which we used to look at activity recognition and social engagement,” Campbell says. In 2019, Campbell won the SIGMOBILE Test-of-Time award for the 2008 publication of a report on CenceMe. The award panel called it “the first paper to demonstrate how smartphones can be used to derive rich behavioral insights continuously from onboard sensors. Since its publication, the work has inspired a huge body of research and commercial endeavors that has continued to increase the breadth and depth of personal sensing.”

After creating CenceMe, Campbell saw the road ahead clearly. Despite the inevitable practical hurdles, he knew he wanted to harness his innovations in smartphone technology to improve lives. That ambition soon became personal, for a tragic reason.

Campbell grew up in a working-class household in Coventry, England. His father was a chef, and after his parents divorced when he was 7, he and his older sister Mary and younger brother Ed were raised by their mother, a waitress who had emigrated from Ireland to Scotland at 13 to labor in potato fields. “There was no expectation of going to university, but she didn’t want us to follow her path,” Campbell recalls.

In secondary school, Campbell landed in a vocational track, but a teacher recognized his mathematical talent. “Mr. Heath was the first person who saw something in me and gave me confidence in my abilities,” says Campbell. He completed a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from Aston University in Birmingham, England—the first person on either side of his family to attend college.

An avid marathoner who is now 65—and the father of two adult sons with his wife, real estate professional Susan Zak—Campbell says his experience as a first-generation college student motivates him to work with first-gen students at Dartmouth. “It’s one of the reasons I love Dartmouth,” he says. “Maybe 15 percent of the undergrads are first-generation, and there is a big support group.” Campbell teaches a special week-and-a-half introduction to computer science to incoming first-gen students, just before they begin their first semester. He also keeps an eye out for them in his courses, meets them outside of class, and works to be sure they get the support they need. “I’m a huge fan of the First-Year Summer Enrichment Program and proud to be a long-ago first-generation student.”

Campbell’s eureka moment with the Nokia phone, and the app he subsequently developed, changed the course of mobile phone technology. But in 2009, Campbell’s brother Ed, who had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, died by suicide. “He was an incredibly smart and capable person. I was brought up with him, and we shared a bedroom together. The family was blindsided when he had his first depressive episode at university,” Campbell recalls. His brother’s death galvanized Campbell’s research. “I completely shifted my focus area and started to think about how we could get insights—particularly about undergraduates at universities like Dartmouth—about the rising risks of stress. Every day I’m reminded of my brother because of my work, and that gives me a great sense of motivation and satisfaction that I’m contributing to this field. It’s not just the next hot topic.”

In 2013, Campbell created StudentLife, a long-term study of student mental health at Dartmouth, using now-ubiquitous smartphones. He and his research team installed the StudentLife app on the phones of 48 student volunteers. For 10 weeks the app tracked the students’ movements and behavioral trends—including sleep patterns and app usage—and matched the information against their well-being and academic performance. This past October at the International Symposium on Wearable Computers, the world’s leading conference on mobile computing, the StudentLife study won the UbiComp 10-Year Impact Award, which recognizes computing advances that have had long-term and pervasive influence on the field. The awards committee cited Campbell’s initial research paper as having “pioneered the integration of mental health research with mobile data mining, addressing real-world challenges in innovative ways.”

In 2017, following a year SPENT as a visiting researcher working on mental health sensing technology at Google and Verily Life Sciences, Campbell updated and greatly expanded the StudentLife study. The follow-up, called the College Experience Study, was a four-year tracking study of student mental health, this time with more than 200 students. The students earned $10 per week during the four-year run of the study. In addition to loading an app that harvested anonymized data from their smartphone and wearables, participants answered a brief, weekly questionnaire on their well-being.

In what is likely the longest mobile mental health study yet conducted, the College Experience app tracked participants’ location via GPS. Accelerometers recorded if a participant was moving or stationary, and the app pulled in any data on the phone from wearables to show a participant’s heart rate and stress level, when that was available.

The app also pulled metadata showing text and call activity, without any call or text content, and it pinged the phone’s microphone every two minutes to check for conversation. “It does not record any audio, but it has conversation detection built into it. One factor of sociability, a proxy, is whether you’ve been around conversations,” says Subigya Nepal, Adv’24, one of the study’s authors, who earned his doctorate in computer science at Dartmouth last year and is now a postdoctoral fellow at the Stanford University Institute for Human-Centered AI.

The combination of the sensing data and the weekly behavioral surveys yielded an integrated body of information to analyze and cross-reference on each participant. For instance, the location information from campus allowed the researchers to make further inferences about student behavior, including social interaction and self-isolation. “At Dartmouth, location often means you’re at the gym,” Campbell says. “It means when and where you eat, it means how much time you spend in your dorm, your attendance in classes, how much time you spend partying in the basement of the fraternities in social spaces.”

Then, in the third year of the research, Covid-19 struck. The project, originally meant to reveal more about stress and anxiety of student life generally, also wound up being a trove of data on the effects of Covid-19 and lockdowns in 2020 and 2021. Published in two parts in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, the College Experience Study found that the participants had increased anxiety and depression compared with the pre-pandemic period. They spent 44 percent less time in public spaces, including gyms and dining halls, and 9 percent more time on their phones than before Covid hit. Campbell wasn’t surprised. What was significant, he says, was that data showing the negative psychological effects of the pandemic and lockdown in the population at large corroborated the general decline in student well-being that Campbell and his team saw from data collected from students’ phones. The researchers had confirmed their method yielded results of significant accuracy.

While Campbell predicts that mobile phone sensing will revolutionize healthcare, the use of technology to assess and treat mental health raises a raft of concerns regarding privacy, safety, and efficacy. With an app like the one used in the College Experience study pulling personal data and transmitting mental health information, keeping the data private and anonymous was crucial. Campbell and his colleagues separated the participants’ identities from their data. The only person who knew participants’ names was the person who registered them for the study. The students were assigned numbers—and that is all the researchers saw. Conversely, no one who had the participants’ names ever saw the data collected.

“If a phone can be a therapist for someone who doesn’t have access, and it nudges them in the right direction, that has amazing scalability.”

Campbell is vigilant about user privacy, and while he recognizes their inherent risk, he says that technological tools such as MoodCapture present opportunities for mental health assessment and treatment that could fill gaps in access to care and supplement current diagnostic and clinical options. “There are pros and cons to both sides. I live in Norwich, Vermont, an area where we have amazing access to therapists and psychiatrists and other clinicians,” he says. “But you go to upstate Vermont and there are no resources. If a phone can be a therapist for someone who doesn’t have access, and it nudges them in the right direction, that has amazing scalability.”

The need for more mental health services is increasing, especially on campuses. According to the 2022 Healthy Minds study, which surveyed more than 350,000 students at 373 schools, mental health issues among college students in the United States are on the rise. The study reported that in 2020-21 more than 60 percent of the students met the criteria for at least one mental health problem—50 percent more than in 2013. The American Psychological Society reported that the Covid-19 pandemic increased urgency to expand mental health services and that colleges still struggle to meet the need.

“Any technology can be used for good or evil, but the pragmatist in me says it’s hard to stop the rollout of technology,” Campbell says. “After my brother’s death, I learned a surprising fact: If a young adult is going to have their first depressive episode, it’s very likely to happen during the college years. My focus has always been on trying to advance our understanding of how technology can help and assist people who might be vulnerable, particularly in the area of mental health.”

Chris Quirk is a freelance writer who lives in New York and Vermont.

If you or someone you know needs support, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. Access Dartmouth’s 24/7 mental health resources here.