Six Hundred Thousand Despots

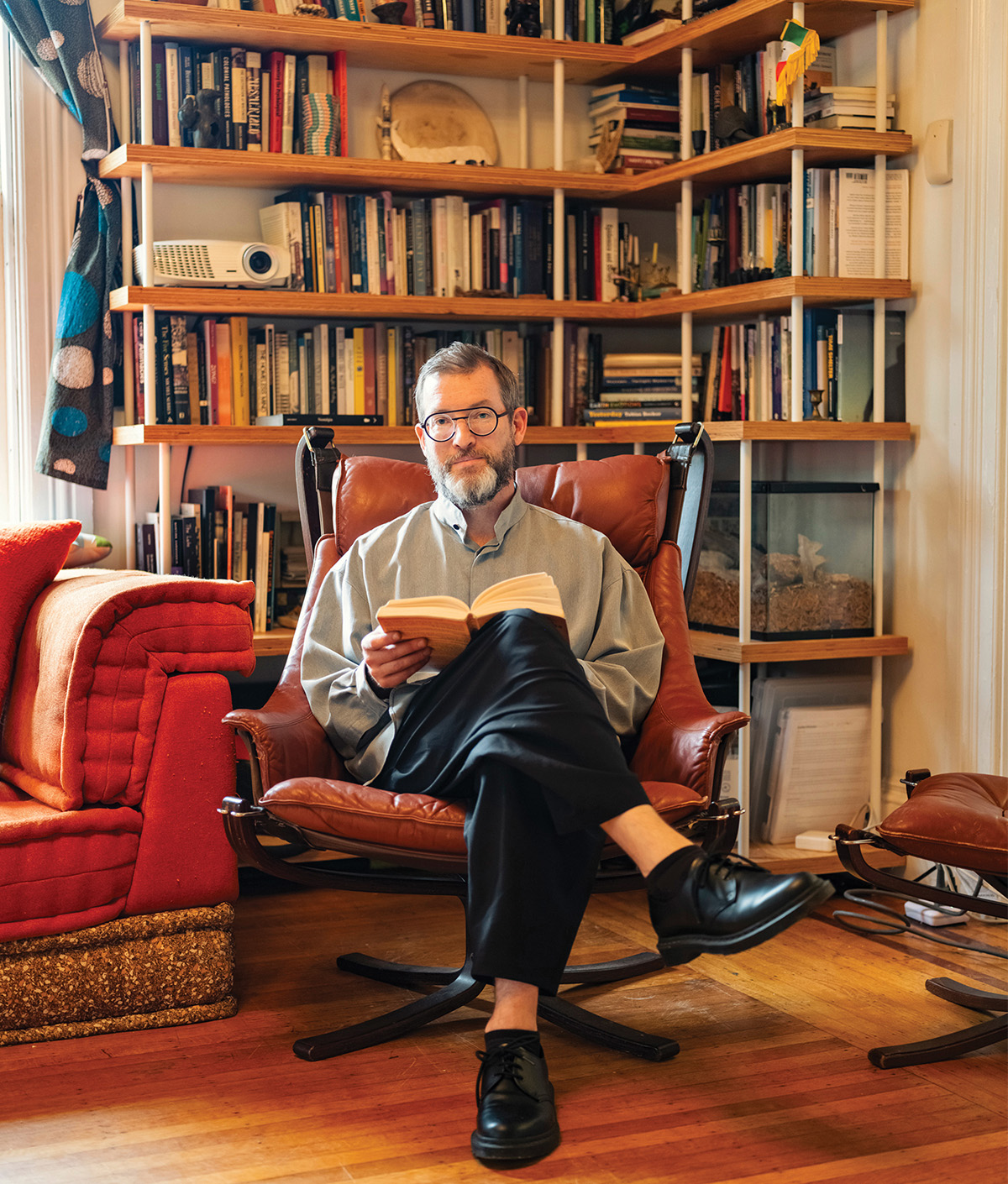

On the night of October 26, 2016, Jonathan Schroeder had just moved into a New Haven attic apartment to start a postdoc year at Yale. He was anxious about job prospects. To burn off steam, he returned to some research he’d been doing for a paper. “I got in my comfy chair and started to putz around on the computer,” he recalls.

Schroeder was looking into the death of the son of Harriet Jacobs, whose 1861 autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, endures as a landmark of American literature. He knew the son, Joseph, had died in Australia. Schroeder dug deep into a database of long-gone Australian newspapers and found it awash with references to men named Joseph Jacobs. No luck.

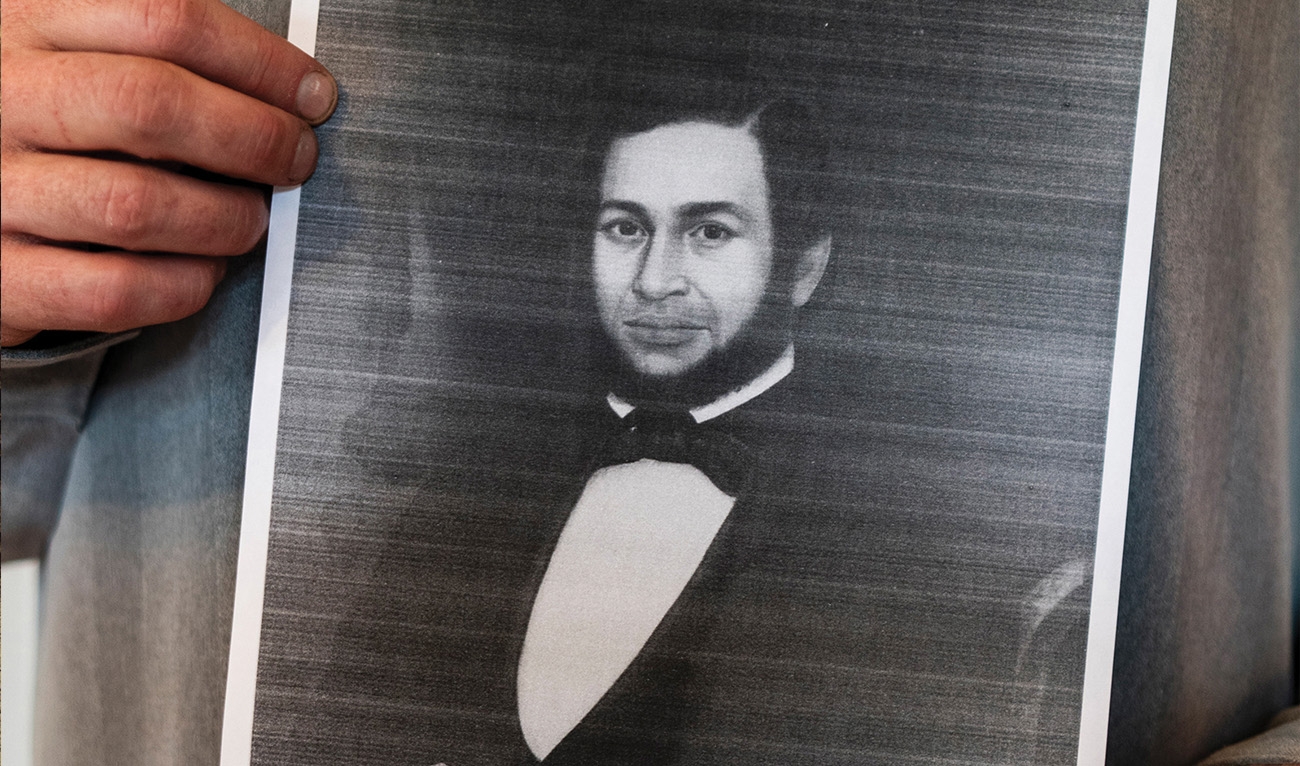

He dug deeper and popped in the name of Harriet’s brother, John Jacobs. To Schroeder’s astonishment, among the search results buried in the archives of the Empire, a newspaper published in Sydney for only 25 years in the mid-1800s, he came across a treasure: A two-part, 20,000-word memoir by a former slave from North Carolina. The tract, which appeared in 1855, detailed the author’s brutal treatment and included a sharp assessment of the U.S. founding fathers and their heralded documents of independence and freedom, which sidestepped the issue of slavery. The account had a provocative title—The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots: A True Story of Slavery—and a provocative byline: “A Fugitive Slave.”

Schroeder immediately started reading. The author, in a voice of icy indignation, had penned a scathing indictment of the 600,000 Americans who owned slaves. Schroeder recognized some of the names and details from Harriet Jacobs’ book. This made him suspect that the unnamed writer must have been her brother, John Swanson Jacobs. About three-quarters of the way into Despots, Schroeder found a smoking gun: The former slave referred to himself by name.

The discovery “sucked the breath out of me,” Schroeder recalls. “I was so excited. I was trying to suspend belief for the first couple of minutes. I had never before come across a new text of literary and historic significance—few people have. I was running around in the attic, with that 1970s wall-to-wall carpeting and fake wood paneling, with my head cut off, trying to figure out what to do.” He called his mother. “I excitedly told her just how important I thought this was.”

A day or two later he sought advice from a friend who is a literary historian. “I don’t know,” she said. “Literary historians don’t make discoveries. Other people do.”

But Schroeder had made a discovery. He reached out to several faculty at Yale, including his sponsor, Caleb Smith, who had just edited the earliest known prison memoir by an African American writer, and David Blight, biographer of abolitionist Frederick Douglass. “I tried to get a sense of what they thought might be important,” Schroeder says.

Despots had been republished in the United States during Jacobs’ lifetime, but under a sanitized title—A True Story of Slavery?—in a severely bowdlerized form. The narrative Schroeder rescued from oblivion is the original, uncensored text, and its unapologetic defiance reveals the mindset of a mid-19th-century Black abolitionist operating without the heavy-handed interference of white editors.

Schroeder delved into other texts—about 88 of the fewer than 100 published slave memoirs—and transcribed the entire newspaper piece to reinforce what he calls his “muscle memory.” He then did a comparative analysis. The Empire piece had no copyright, so he decided to publish it as the definitive version and add a biography.

The book Schroeder published last May fills the gaps in Jacobs’ cursory account of his experiences as a free man. A sixth-generation slave, Jacobs escaped in 1838 and spent the rest of his life traveling and working as a sailor, gold miner, and abolitionist. Schroeder reconstructs Jacobs’ life in England, Australia, and aboard numerous ships sailing on every ocean.

The original narrative primarily evokes his life growing up with a succession of owners and his angry denunciation of the system that entrapped him. Refusing to call his owner’s children “Miss” and “Master,” Jacobs is unable to “make myself believe that they had any right to demand any such humiliation from me.” After observing fatal beatings, he acidly diagnoses “death caused by moderate correction, which the state of North Carolina does not punish a slaveholder for.”

Jacobs’ memoir radically departs from what Schroeder calls “the old humanitarian contract” between Black abolitionist memoirists and their liberal white audience. Where slave narratives—including the famous one by Jacobs’ sister

Harriet—typically used heartrending portrayals of hardship to elicit the sympathies of white readers, Jacobs set out to indict the system itself. Pointing readers toward politicians, laws, and institutions, he described slavery as “the cornerstone of American Republicanism,” and the Constitution as “the bulwark of American slavery.” Jacobs wanted his readers to feel implicated.

“Jacobs was a full-time sailor,” Schroeder says. “I think that gives him a perspective on the U.S. that allows him to provincialize it. Americans often lose sight of the rest of the world and inflate our idea of America to grandiose proportions.” Writing from a distance gave the Black author “free rein to reconfigure the relationship between liberty and truth.”

Schroeder, who now works as a lecturer in literature at Rhode Island School of Design, majored in classical studies and English, wrote for The Dartmouth, and was a presidential scholar. Following a Fulbright scholarship in Singapore, he earned his master’s from Brown and his doctorate from the University of Chicago.

Abolition historian Manisha Sinha calls Schroeder’s work an “an amazing act of recovery.” Jacobs and other Black abolitionists were ahead of their time, she notes: “The tragedy is that most of us today don’t know much about these unsung heroes of American democracy.”

The discovery “sucked the breath out of me,” Schroeder recalls.

Jacobs’ final chapters meticulously dissect “the laws of the United States respecting slavery,” including the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. “He satirizes and parodies and criticizes the language of the document in order to write between the lines of it—to take the power from a document that had disempowered him,” Schroeder says. Jacobs closes with a human rebuke that’s majestic in its simplicity and clarity. “No law,” he insists, “can make property of me.”

Schroeder believes the memoir marks a major contribution to the tradition of Black protest that runs from David Walker’s Appeal (1829) through present times and the Black Lives Matter movement. “This work now stands to open new routes for the study of race, ethnicity, and migration,” he says. For Schroeder, the publication of Despots has been career changing. Its quick inclusion in curricula has provided him the chance to share Jacobs’ experience with students from high school to graduate school. “I wanted to bring Jacobs’ narrative back into the world and have it make a difference,” he says. “But this has exceeded anything I hoped for.”

Rand Richards Cooper is a culture critic. He lives in Hartford, Connecticut.