On the evening of August 25, 2024, Jennifer Whitcomb was at home in Juneau, solo-parenting her three kids while her husband, Colin Vogler, was at sea piloting a Holland America cruise ship up the inside passage of southeast Alaska. Just before turning in for bed, she received a call from the Coast Guard’s Joint Rescue Coordination Center, which had heard from the air station on Kodiak Island. The station had been in contact with a bulk cargo ship drifting without propulsion 170 nautical miles southeast of Adak, far out the Aleutian chain.

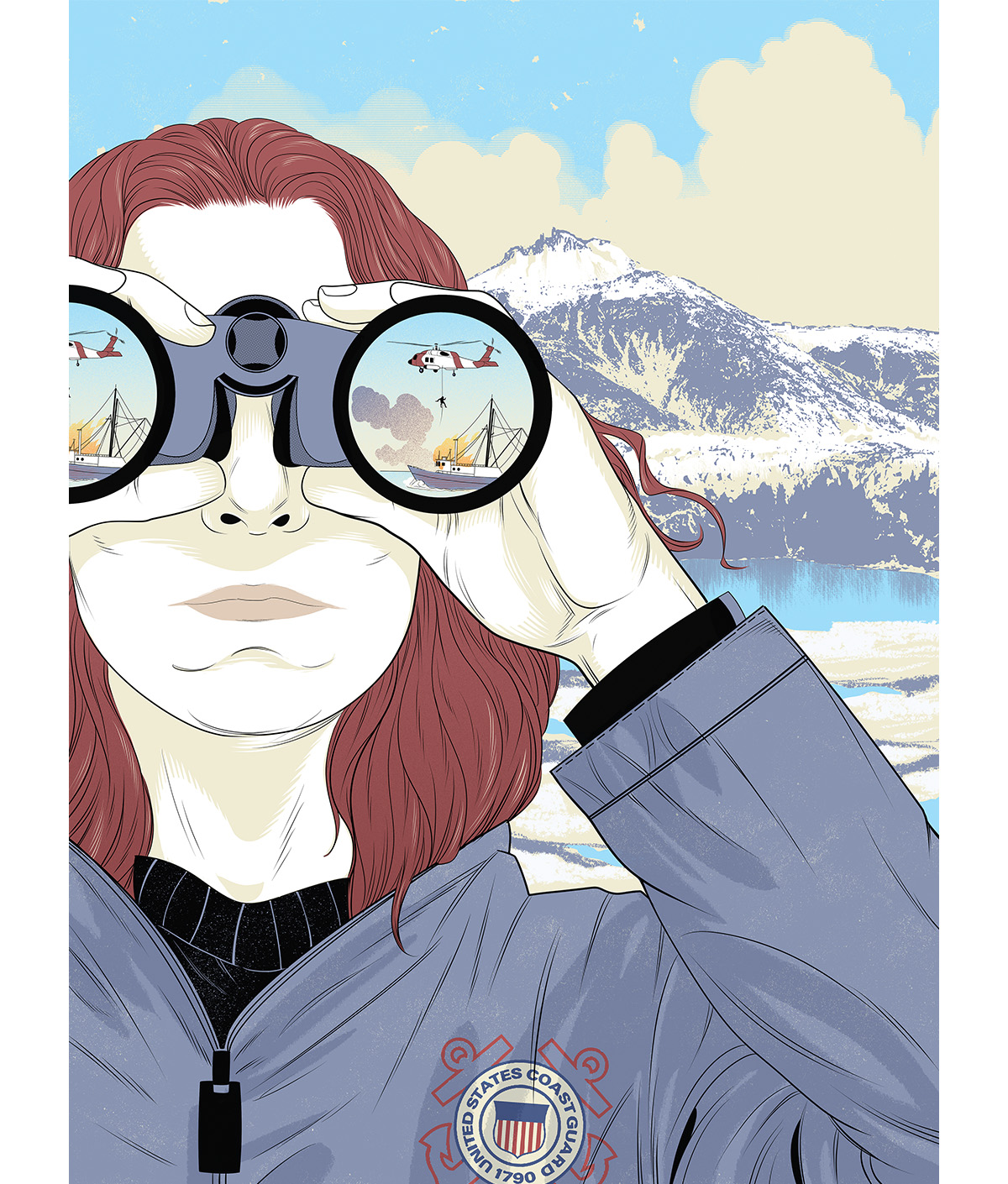

Whitcomb, manager of the Coast Guard’s search-and-rescue (SAR) program for the state of Alaska, is used to getting distress calls at all hours. She serves, essentially, as the subject matter expert for the intense risk-reward calculus used in the most brutal of the Coast Guard’s nine SAR districts—nearly 4 million square miles of remote and weather-battered ocean stretching out through the Bering Sea and up to the North Pole. Kodiak, the branch’s westernmost jumping-off point for Jayhawk rescue helicopters and HC-130 Hercules fixed-wing aircraft, was calling Juneau for her advice.

The cargo ship’s captain had reported mechanical difficulty and estimated the time of repair at four to six hours. That call, Whitcomb learned, was more than 40 hours and a series of revised time estimates ago. Whitcomb got as much information over the phone as she could. She told the watch stander to sit tight and keep her informed.

The next morning, at the District 17 command center she operates, Whitcomb met with her team and talked over the what-ifs that had kept her awake the previous night. The cargo ship’s captain hadn’t been requesting Coast Guard assistance. But vessels in trouble and the Coast Guard don’t always see things the same way. What Whitcomb knew was this: A 590-foot-long ship under a Marshall Islands flag with 24 people aboard was disabled, reporting no injuries and no water coming in, adrift way the hell offshore in okay weather and moderate seas. The wind and current could have brought the vessel broadside to the swells, but a bulk ship carrying 16,000 long tons of cargo would be sitting almost squarely in 11-foot waves. This wasn’t a deadly combination of no propulsion and no stability. There were 210,000 gallons of residual fuel and 39,000 gallons of distillate fuel on board, but that far out at sea there was little chance of an Exxon Valdez-like environmental catastrophe. “I have low apprehension about this,” said Whitcomb. “Do you all agree?”

She instructed Kodiak to stand down. Then, she diverted a Coast Guard cutter bound for Dutch Harbor, just to get help nearby in case something went south. “We met the response in the middle” is how she put it later. Ultimately, the cargo ship contacted a tug to pull it before the crew isolated and replaced a faulty fuel injector and went on its way.

There are three official phases of a search-and-rescue case—uncertainty, alert, and distress. In this instance, Whitcomb and her team gamed out scenarios and debated whether the cargo ship’s situation ever rose to the level of uncertainty. “It can become almost a philosophical question,” she says. “I call it Schrödinger’s SAR,” referring to the quantum physics thought experiment where a cat inside a sealed box is simultaneously dead and alive until its state is known for sure. In this case, a vessel was insisting that it was not in any distress, but its insistence was becoming less credible. “We had to look at it through two lenses at the same time,” says Whitcomb. “It was actually a good academic exercise.”

The work Whitcomb does for the Coast Guard, though, is far from academic. (If you want a glimpse of the stakes, check out Deadliest Catch or Coast Guard Alaska on TV.) As the search-and-rescue program manager, Whitcomb makes the go/no-go calls on putting the Coast Guard’s assets into motion and into potential danger: assets that include multimillion-dollar machines and the lives of pilots, air crews, boat crews, and rescue swimmers, with critical time and distance calculations alongside variables such as daylight, terrain, ocean conditions, flying conditions, fuel use, the status of equipment, the experience and fatigue and readiness of human beings. Against the risks, she weighs the alternatives and the chances for a successful mission: transporting a cardiac patient to Anchorage by helicopter, hoisting crew members off a sinking ship; plucking survivors from 36-degree seas. “It’s chess, with weather,” she says. “Alaska is my chessboard. How can we move the pieces around to do the most good with the least amount of risk?”

She was born to the work. Her parents had met in the Air Force in Southeast Asia. Her mother was an intelligence officer; her father has written history books on combat search and rescue. Her family tree includes every branch of the U.S. military. Growing up in Kansas and Fairfax County, Virginia, Whitcomb says, “The ethic of service was something I was raised on.”

Coming to Dartmouth out of the high-pressure Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, Whitcomb struggled to find her bearings. Her beginning Chinese class “kicked my butt” that first semester on campus. Her confidence shaken, feeling rudderless, she skipped a semester to hike the entire Appalachian Trail to steady herself.

Two experiences at Dartmouth had inspired the hike. She had met her first-ever thru-hiker in the White Mountains during her first-year trip. The 19-year-old man was guiding his blind father along the entire length of the Appalachian Trail. Whitcomb was moved by the interaction. A few months later, back in Hanover at the Dirt Cowboy Café, Whitcomb met an eccentric 38-year-old thru-hiker known as “Baltimore Jack.” He encouraged her to hike the trail and helped her plan a trip. During the following spring and summer, the two of them would spend a thousand miles together or within a day’s hike of each other as they completed the trail.

Whitcomb needed to reapply to get back into Dartmouth, which she did with newfound confidence and purpose. She majored in geography. She also had no hesitation about inviting her friend to live in her dorm room. Whitcomb propped up her River Cluster bed with cement blocks and let Baltimore Jack stay below for a few months while he looked for a more permanent situation. “The kids on the floor didn’t seem to mind a 40-year-old living there,” says Whitcomb. “He helped them with their history papers and also could buy alcohol.”

Geography professor George Demko’s seminar Landscapes of Murder made a deep impression. Demko taught her that a good, place-based mystery was better than any travel guidebook for getting to the heart of cultural, social, and physical geography. Whitcomb was taken by the notion of detective work—how close observation, asking the right questions, gathering clues, and thinking outside the box could reconstruct events and an unseen world in the mind’s eye.

She attended Coast Guard officer training in Connecticut in 2001, set on a career as an officer and helicopter pilot. She followed the advice to get some experience on the water first, that going afloat would ultimately make her a better pilot. She accepted a post in Seattle as a communications officer. Like junior officers everywhere, Ensign Whitcomb was handed all manner of scutwork and collateral duties, one of which included standing watch in the sector’s search-and- rescue center. She took to the work instantly and enjoyed the intellectual challenge of piecing together from maps and words and numbers what was unfolding out there on the water. She had a knack for it and good instincts. She was single and unattached and threw herself into the learning.

She memorized the charts and shipping channels of Puget Sound. She read search-and-rescue histories, internalized the lessons. Her initiative attracted a couple of mentors, who would quiz her, take her out to various state parks along the water, ask her, What do you see from here? Imagine there’s a flare coming from a boat over there. What would that look like? What if somebody set off a firework from the beach? How would those two look different?

“There was no manual that told them to do that,” Whitcomb says. “They were just into it. They had done time on cutters and in stations and understood what I call a waterline view of search and rescue. They turned me into a maritime detective. They helped me build a three-dimensional SAR brain.”

In 2003, Whitcomb shipped out on the Polar Star on a six-month mission to Antarctica’s McMurdo Station. Aboard the icebreaker, she absorbed the perspective and nomenclature of shipboard life, more layers of knowledge. Her favorite part of the mission came in the South Pacific when the Polar Star was the closest Coast Guard asset to a vessel in distress and temporarily diverted to assist. “That’s the only time I was ever at the tip of the spear,” she says.

Whitcomb pivoted away from her ambition to fly helicopters. Following a three-year tour, she returned to her old unit in Seattle and asked if they’d reinstate her, as a reservist, and get her back to SAR work. “Hell, yes,” said Captain Scott Robert, her former commanding officer.

“Our crews are biased for action. Jen is the anchor to that bias.”

For a career in search and rescue, Whitcomb’s timing couldn’t have been better. She had formally begun her duty in Seattle just one day before the horror of September 11, 2001, which changed everything across all the military branches. The Coast Guard, with expanded responsibilities tied to homeland security, created a handful of civilian SAR positions in each of its rescue coordination centers. The positions—freed from active-duty requirements—underscored the importance that continuity played in the acquisition of local knowledge and the building of relationships with local responders and frontline workers. Whitcomb got the job for Coast Guard District 13, which covers all navigable water throughout the Pacific Northwest.

She discovered she was adept at navigating the contours of the search-and-rescue world. She became an expert on Puget Sound, the coasts of Washington and Oregon, and the Columbia River. She built relationships and trust across agencies and up and down the chain of command, made a point to meet people in person, and earned a reputation for resisting the politics that got in the way of doing the right thing. “My personality turned out to be better suited to the civilian side,” she says. “I tend to have opinions and run my mouth. You get in less trouble doing that if you’re not wearing a uniform.” She loved working out of Seattle and likely could have comfortably stayed there until retirement.

But it was the comfort of the job that eventually began weighing on her, especially as she kept hearing stories of the harrowing and logistically complicated rescues happening up in the far north, out of Kodiak. A job opened up in the summer of 2009 in the SAR command center in Juneau, and she jumped.

In Juneau, the cases, and the stories, intensified with the expanded geography. Two moments in particular proved pivotal.

One: Standing watch in the command center that October, Whitcomb heard a distress call come over the radio from a fishing boat on fire in Chatham Strait. The nearest vessel, the Alaska state ferry Taku, diverted and pulled off a resourceful rescue in 35-knot winds that earned its crew an award from the state government. Impressed, Whitcomb went out of her way to meet the captain and mates who had orchestrated the rescue under pressure. She and the chief mate, Colin Vogler, married two years later.

Two: Paul Webb, an accomplished cutterman and quartermaster whose experience and longitudinal knowledge of Alaskan search and rescue was legendary, announced his retirement in 2022 from the District 17 SAR management position. Nine years earlier, Whitcomb had stepped away from her career to raise her children. Webb had groomed a successor, but he encouraged Whitcomb to apply and get her name back into circulation. Whitcomb had kept her eye on the position since she’d arrived in Juneau. She made the finalist round on the strength of her experience and reputation.

With two weeks to prepare for the final interview, she called everyone she knew in the district to ask what had changed in the time she’d been away and what they hoped would change moving forward. She had kept current with the literature, had helped her husband study for his pilotage exams—which require drawing more than 30 navigational charts by hand and from memory. She brushed up on international maritime law, read case histories, nerded out on search-and-rescue podcasts. She took over for Webb in February 2023.

Her boss, Captain Vincent Jansen, says she has earned respect remarkably fast. “Everyone knows she’s been there and done that,” he says. “She’s worked every job there is in the command center, so people trust her. She’s a great mentor, a great listener. SAR is messy work—we never have all the details before we can make a judgment. Our crews are biased for action. Jen is the anchor to that bias.”

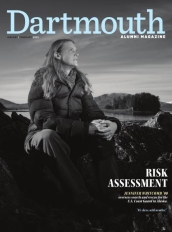

Eighteen months into the job, Whitcomb stands and looks out the window of her sixth-floor office in the massive federal building that looms above the flats on the northern edge of downtown Juneau. She is tall, outdoorsy, with shoulder-length, reddish-brown hair hanging loosely above a turtleneck and fleece jacket. A stack of books on famous Alaska rescues rests on a table, and a large state map covers a wall. After four months of single parenting while Vogler has been at sea, she says she’s been living in the red zone for stress but can’t show it. “My bearing is contagious,” she says. “If I’m calm, my kids are calm. The room is calm.”

Outside, the September day is raw. Low, dark clouds obscure the steep surrounding topography. The actual command center—a classified space a short walk from Whitcomb’s office, filled with computer monitors and high-tech comms—looks like a miniature version of Houston’s mission control. Its lack of windows bothers Whitcomb. She prefers to look out a window, where she can see water and weather and feel connected to the place and the people whose lives she feels responsible for.

It’s been a busy last day of a quiet work week: a successful search and airlift of a missing hiker and pet dog down in Sitka, a potential PIW (person in the water) in Vallenar Bay that turned out to be a false alarm, a 46-foot trawler taking on water with a 77-year-old man aboard in Icy Strait who was saved by a fellow boater who picked up the radio distress call. Whitcomb had okayed the deployment of a helicopter out of Sitka Air Station for that one. With the helo in the air and the rescue under control, it was an easy call to divert to Hoonah for a medevac of a 72-year-old woman with abdominal and back pain running a high fever.

Back home early after picking up kids from school, Whitcomb moves around the kitchen of her sprawling house on the Douglas Island side of the channel, preparing for what’s become a weekly Friday night community pizza party. A mix of kids and adults are expected, including Jansen and a couple of 5-year-olds, who will play the next day in the rain on the rec soccer team Whitcomb coaches.

Just before 5 p.m., a tutor is giving reading lessons to June, Whitcomb’s third-grader. Her sixth-grader, Christopher, plays on the Nintendo in the living room. One of Whitcomb’s two cell phones buzzes—the phone that means something somewhere is sinking or on fire. She picks up and disappears into a quiet bedroom. The command center in Juneau has received a 406 EPIRB ping from a vessel 100 nautical miles southwest of Adak. The satellite signal carries scant information: It originated from a boat registered in Newport, Oregon, under the name Alaska Trojan, a 127-foot long crabber with six crew aboard. The signal, sent from a small handheld device, could have been initiated in only two ways: by a crew in distress or by an automated warning triggered when it is submerged.

Whitcomb knows it takes eight hours for a helicopter to reach Adak, and three hours for a C-130. Kodiak is preparing to launch both and is readying two flight crews: a “Cinderella” team to make the long flight out, and a “hero” crew to follow in the C-130 and relieve the first crew after the refueling in Adak. They’ve called for Whitcomb’s blessing of the launch order. She gives it, then strolls back to her kitchen.

During the next two hours, Whitcomb dances between two worlds, hosting a gathering and disappearing into the bedroom, all while portraying a calm bearing and rapidly assimilating weather reports, ocean conditions, and updates from the air station. Jansen, without asking, steps in, puts more frozen pizzas into the oven, and starts serving.

Kodiak is still working on raising a second crew, delaying the launch. Whitcomb’s mind races. She’s planning on a long night. She games scenarios and considers what-ifs. For the first time, she starts thinking about what she may have to tell the next of kin.

The phone buzzes again. It’s command duty officer Lieutenant Tyler Templeton on the line, calling with an updated estimate for when a rescue helicopter could reach the scene. Whitcomb has always respected Templeton’s professionalism, his military coolness under pressure. “Oh, wait,” Templeton says. “Give me one second, ma’am. The guys down in front are fist-bumping. I may have some good news for you.”

In the kitchen, Jansen has moved to the sink while his wife, Ellie, collects and hands him dishes. Whitcomb joins him there. “Thank you, Captain,” she says, breathing out. “I can take it from here.”

Jim Collins is a frequent contributor to DAM.