Where the Heart Is

AlexAnna Salmon ’08

In February 2008, just months before Salmon was set to submit her thesis, graduate, and join Teach For America, her father, Daniel, died in a plane crash. He was piloting his Cessna 170 home from a meeting in Anchorage, Alaska, when it went down. He was 49. A week later, he visited Salmon in a dream and changed the trajectory of her life.

In the dream, they were flying together—“in a float plane, which he didn’t even fly,” she clarifies—when suddenly her father removed his hands from the controls. “I was really angry. I ended up landing the airplane, and when I got out, I was like, ‘That wasn’t funny!’ I had an attitude. He said, ‘I knew you could do it.’ ”

For 22 years, Salmon’s father had been the tribal administrator of Igiugig Village, a community of about 70 people—mostly Yup’ik, Aleut, and Athabascan Indians—in southwestern Alaska at the mouth of the Kvichak River and Lake Iliamna, home to the largest sockeye salmon run in the world. Life in Igiugig revolves around hunting, fishing, and gathering. No roads lead to or from the village, so going anywhere requires a plane. Daniel oversaw housing and infrastructure development, and his passion for education, community service, and youth transformed the village.

“My father believed in me, and whether he was alive or not, he was still conveying that through the dream world—or I was subconsciously conveying it to myself,” Salmon says. “That dream made me realize there were bigger things than finishing my classes.”

Dropping her postgrad teaching plans, she returned home after Commencement and started working as Igiugig’s special projects coordinator. Salmon immediately tackled one of her father’s ideas by creating a community greenhouse for a food security program. Before the end of the year, village leadership asked her to become tribal council president.

At 22, and less than a year out of college, Salmon was suddenly in charge of Igiugig’s local governance—infrastructure, services, grant programs, and for-profit tribal subsidiaries. She was also raising two foster daughters, overseeing the land department of Igiugig Native Corporation, and running her father’s freight company. “It was an immense workload,” she says. She led the village during the day, wrote grants at night, took an accounting class, and in 2021 earned a master’s in rural development from the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“AlexAnna had the whole world of opportunities open to her, and she said, ‘I want to go back home and serve my community,’ ” says

Halay Turning Heart ’08, the grants administrator of Igiugig Village Council, who met Salmon at Dartmouth. “She leads from the heart. She has a vision for the good of the whole region, not just Igiugig.”

Fifteen years later, Salmon continues to focus on nationhood building—reversing the cultural genocide of the last 100 years and advocating for Igiugig in all aspects of life. She has established a Yup’ik language restoration program, built a multimillion-dollar health clinic, upgraded the village generator, and helped launch an emerging leaders course for young people. Under her leadership, Igiugig became the first tribe in the United States to receive a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission pilot permit to operate a water-powered alternative energy system not connected to a dam, which generates electricity from the Kvichak River and reduces the village’s reliance on diesel fuel. Today, Igiugig has a zero crime rate, a five-star school, and a recycling program that helped the community earn its reputation as Alaska’s cleanest rural village.

“I live every day to still make my father proud, and I think we have surpassed his expectations,” says Salmon, whose salary comes from grants for the projects she directs. She is also a member of the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History’s advisory board. She now has four children and plans to marry this summer. “My dad used to say, ‘Maybe you should go to law school.’ Everyone has their own idea of how I can help this community. At the end of the day, it’s being the best elder I can be. I’m really an elder-in-training. A teacher said, ‘Does it feel odd to you that you’re viewed as a culture bearer?’ Maybe that’s been my role all along.”

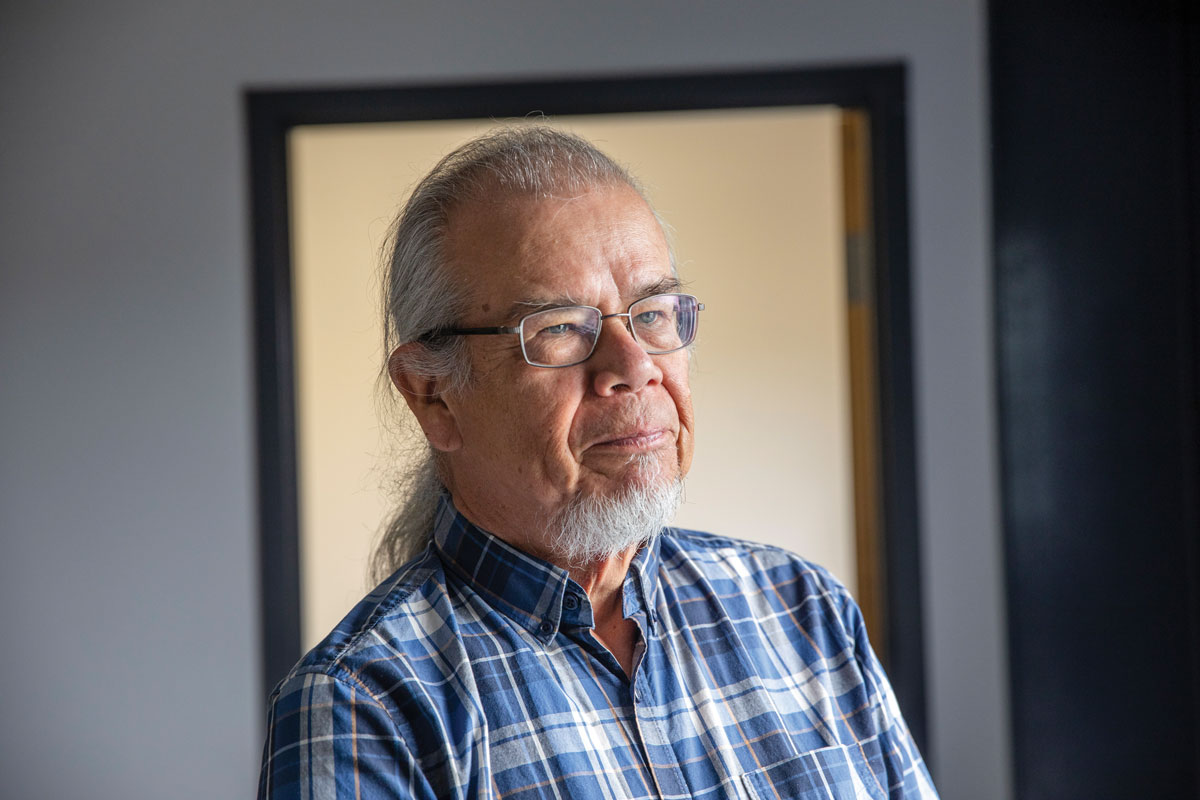

Brian Maracle ’69

Maracle, whose Mohawk name is Owennatekha, wants to clarify: “I haven’t studied linguistics, and I’m not an expert,” he says. Still, he has spent the last 25 years transforming how his ancestral language, Kanyen’kéha, or Mohawk, is taught, helping to ensure it remains a living language for generations to come.

Maracle did not grow up speaking the language, nor did his parents. His family left Ohsweken, on the Six Nations of the Grand River in southern Ontario, when he was a boy. After paying for Dartmouth by “pounding nails” as a carpenter, then pursuing a career in journalism and radio, he returned home in the 1990s and started to study Mohawk. But it was a dying language. For generations, residential schools and colonization had aimed to eliminate Indigenous languages and cultures, forcing Native people to assimilate into white society.

Mohawk is incredibly hard to learn because one word often equates to an entire sentence in English. Words also contain smaller elements called morphemes that must be assembled with other morphemes in the proper sequence. Traditionally, schools taught Mohawk by focusing on whole words, which meant students memorized entire sentences instead of understanding how to construct them using morphemes. And teachers—typically elders and first-language speakers—didn’t understand how difficult it was for English speakers to learn the complex language. Maracle likens it to learning how to drive a standard car from an instructor who only drives automatic.

After trying and failing to learn Mohawk through a full-time immersion program, he set out to find a better approach. That’s when he stumbled across the work of a Mohawk scholar who had developed a teaching method that involved stringing together morphemes. “Inspiration hit me,” says Maracle. “I said, ‘All I have to do is figure out how to explain this to students.’ ”

In 1999, Maracle and his wife, Audrey, or Onekiyohstha, established an adult immersion school, Onkwawenna Kentyohkwa, or Our Language Society, in Ohsweken. Maracle began teaching Mohawk during the school’s second year using a curriculum he designed called the root-word method, which focuses on morphemes, not whole words. “When you build a house, the first tool you pull out is not a paintbrush,” he explains. “Don’t start there. You pull out a shovel—or a root word. This enables students to think in the language, to understand and say things they’ve never heard before.”

Today, 25 Onkwawenna graduates teach Mohawk at schools across southern Ontario. Program alums founded a Mohawk immersion elementary and middle school and established the first Mohawk-speaking longhouse at Grand River. Some write rap songs and recreate Star Wars episodes in Mohawk. After attending the school’s part-time online program, Marc Miller, Canada’s immigration minister, delivered a speech in Mohawk to the house of commons in 2017—the first time the language had been spoken in either house since the Canadian Confederation in 1867.

Two other Mohawk communities currently use Maracle’s root-word teaching method, and the Seneca and Tuscarora territories in western New York are applying the principles to their adult language programs. Onkwawenna, which enrolls no more than 12 students a year, recently received two years of grants from the federal government. All other funding has come from local families. The school has also teamed with the National Research Council to develop a digital Mohawk verb generator as well as a voice synthesizer that translates Mohawk text into realistic-sounding Mohawk speech.

“The way I was taught to combine the parts and pieces of the language to build words for myself was liberating,” says Jeremy Green, an Onkwawenna graduate and assistant professor of Indigenous studies and Indigenous languages at York University in Toronto. “For a people who have experienced 500 years of colonization being constantly told how to be, act, and speak, this was an emancipatory experience.”

Several years ago, Green stopped by Maracle’s home to catch up with his former teacher. As they stood outside speaking in Mohawk, Green’s 4-year-old son sat in the car, refusing to get out. Eventually, the boy rolled down the window and said, “É:so ken kontinákere ne yakonererhohárhos ne kèn:tho?”—“Are there a lot of bees around here?”

“It’s a mouthful, and he said it easily and quickly,” Maracle recalls. “There’s the boy of one of my students speaking Mohawk naturally, and I thought, ‘Wow! This is working.’ ”

Aja DeCoteau ’02

Growing up on the Yakama Reservation in Wapato, Washington, DeCoteau spent many days watching her grandfather fish the Klickitat River. She’d sit on wooden scaffolding built into the rock and, sometimes for eight hours at a time, listen to the roaring water and watch him dip-net for salmon with a long pole and a wide net. Later, her grandfather would bring the catch to her house, cover the kitchen floor in newspaper, and teach her how to filet salmon. It’s one of her most cherished childhood memories.

It makes sense, then, that DeCoteau has spent her career protecting and restoring salmon in the Columbia River Basin. As executive director of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC), her work focuses on reversing the decline of salmon and other fish in the basin, protecting tribal treaty fishing rights, and supporting fishers.

“I always knew I’d come back home to support my people,” says DeCoteau, who majored in environmental studies and Native American studies and earned a master’s in environmental management from the Yale School of the Environment. “We have been on this land for thousands of years, and as a tribe and a culture, we have grown alongside salmon our entire history. It’s part of our language, songs, ceremonies, dances, and in the way we pray and how we give thanks. It’s how we live our lives.”

Salmon are at the heart of the Native American creation story, which begins when the Creator gathered all the animals and plants and asked each one for a gift to help the new humans survive once they arrived. “The first to step forward was Salmon, which said, ‘I give my life so that humans can eat,’ ” DeCoteau explains. Water volunteered next, promising a home for the salmon. “Because salmon gave themselves up for us, it’s our responsibility to take care of them,” DeCoteau says.

CRITFC, formed in 1977 by the Nez Perce, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Yakama tribes, champions tribal rights and resource protection for native fish and Native people in the Columbia River Basin. With a $42-million operating budget, CRITFC employs 142 people, including biologists, legal experts, hydrologists, and police officers.

“Aja is the best hire I ever made,” says Paul Lumley, a former executive director of CRITFC who is now CEO of the Cascade AIDS Project in Portland. “She’s got a dedication and professionalism that are unparalleled. She’s taking salmon restoration work to a new level.”

In 2022, DeCoteau released the commission’s tribal energy plan, aimed at reversing the declining salmon and steelhead populations in the basin, fighting climate change, and safely harnessing renewable resources. Among the group’s 43 recommendations is a case to amend the Columbia River Treaty to include energy resources that boost protections for wildlife and fish while reducing carbon emissions.

DeCoteau also oversees the commission’s genetics research lab, leads the Columbia River Inter-Tribal police department, and runs the Coastal Margin Observation and Prediction Program at the mouth of the Columbia River in Astoria, Oregon. “A certain population of salmon will come back in three years, but when salmon don’t come back, we don’t know why,” she says. “Is it algae blooms? Overharvesting by shipping vessels? This program tries to fill in the whole story of the full life cycle.”

Before taking the helm in 2021, DeCoteau managed the commission’s watershed department for 12 years. She lives in Portland with her husband and their three children, whom she’s teaching to filet fish on the kitchen floor. “My husband is a first-generation Italian, so we really merged cultures. I knew Italians from mafia movies, and he knew Natives from spaghetti Westerns.”

Last year, DeCoteau became the first Native American to serve on the U.S. National Park System Advisory Board. She’s also the first female executive director of CRITFC. “Being the only brown person, the only younger person, the only younger brown woman—it’s not new for me. I feel proud of it,” she says. “I can think of many instances where people said I wasn’t ready for a job, or I was too young. Fortunately, I didn’t listen to them.”

Devin Buffalo ’18

Hockey has been a way of life for as long as Buffalo can remember. Growing up in Alberta, Canada, between his father’s horse ranch in Samson Cree Nation and his mom’s place in nearby Wetaskiwin, he spent his childhood playing mini sticks, grass hockey, and ice hockey. On weekends he watched his older brothers compete in the junior leagues against future National Hockey League players.

“My dreams were set at a young age,” says Buffalo. He wanted to be an NHL goalie. He had natural talent and drive, but as an Indigenous athlete he faced racism from players, coaches, and fans. “The stereotype was that we were lazy hockey players or drunks,” he says.

Once a fan taunted Buffalo, “Go back to the reserve. Go back to your teepee.” During a heated playoff game an opponent sneered, “You’re just another f*ing Indian.” The goalie learned to hide his pregame rituals—listening to pow wow and round dance music, and using sweetgrass, sage, and cedar to smudge, or cleanse, the air—to minimize the mockery.

He focused on working hard, connecting with coaches, and being a dependable teammate. “That was partly why I wanted to go to an Ivy League school and play pro hockey,” he says. “To prove I could do it—a Native could do it. These stereotypes weren’t true.”

In 2010, when he was in 12th grade, Buffalo made the U18 AAA hockey team, the highest level of minor hockey in Canada. The next year, he landed a spot on the Flin Flon Bombers in the Saskatchewan Junior Hockey League. Later, at Dartmouth, he leaped from third string goalie to team MVP. As a senior, he earned second team All-Ivy honors and was nominated for the prestigious Hobey Baker Award, given to the top NCAA men’s ice hockey player, and the NCAA Hockey Humanitarian Award.

After graduating with a government degree, he played minor pro hockey for a year, until injuries sustained in a car accident derailed his NHL ambitions. It was 2019, and he suddenly had to come up with a new dream to chase.

He found it where he least expected.

“No one would have convinced me in high school that I’d come home. That was the one thing I didn’t want to do. I wanted to be successful in a big city, like New York or Boston,” he says. “But there was always something missing at Dartmouth. It was that connection to home, to my family, to the land.”

In early 2020, he launched Waniska Athletics, an organization that mentors and supports young Indigenous hockey goalies, giving them access to specialized training, academic support, and motivational thinking. “It’s tough trying to make a non-Indigenous team. I know that struggle. I dealt with it my whole life,” he says. “A lot of kids get discouraged, so I knew there was an opportunity to help.” Waniska, which means “wake up and rise” in Cree, has held all-expenses-paid hockey camps for more than 60 goalies in five locations, from Alberta to Ontario.

“Devin focuses on things a goalie needs to work on: edgework, proper positioning, speed, explosiveness, the mental side,” says Carter Van Os-Buffalo, 12, a cousin of Buffalo’s who has attended three Waniska camps. “He inspired me, but I still have a long journey ahead. I want to play college hockey so I can get an education, like what Devin did. If hockey doesn’t work out, then I still have a good degree.”

Buffalo has taken that strategy one step further. In 2021, he started law school at the University of Alberta. Now in his final year, he wants to work with Indigenous nations and businesses to help them gain economic independence and sovereignty. “There’s a lot of work to be done,” he says.

Abigail Jones profiled Sian Beilock in the May/June 2023 issue of DAM.