There are cult movies and there are midnight movies—and then there are movies so far out on their own wavelength of weird that they serve as a secret handshake among the cognoscenti. Films whose obscurity and arcana become badges of honor. Where the dialogue functions as a password that separates insiders from the clueless masses.

“Wherever you go…there you are.”

“Laugh-a while you can, monkey-boy!”

“Why is there a watermelon there?”

If you recognize those lines, you have probably seen The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension more than once since its release in 1984 to indulgent reviews, baffled audiences, so-so box office returns, and a die-hard constituency that continues to celebrate it online and elsewhere as one of the most delightfully original comedy sci-fi action whatsits of the last 40 years.

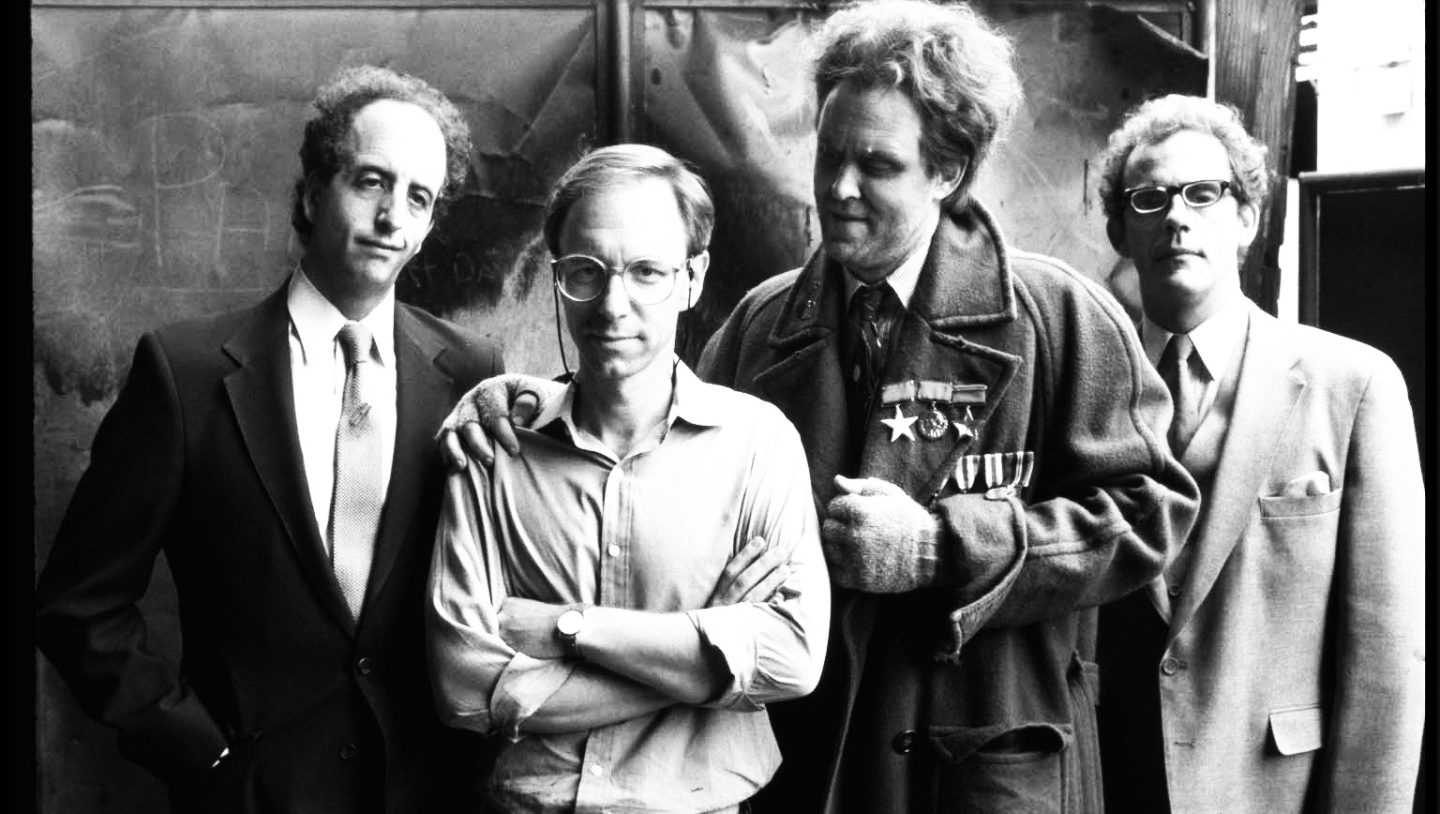

Directed by W.D. Richter from a script by Earl Mac Rauch ’71, Buckaroo Banzai stars Peter Weller (RoboCop) as the title hero, a dashing physicist/brain surgeon/race car driver/rock star/Zen guru. His posse, the Hong Kong Cavaliers, includes Jeff Goldblum as “New Jersey,” a fellow doctor dressed in cowboy regalia. John Lithgow hams it up outrageously as villain Lord John Whorfin, an alien Lectroid from Planet 10 who inhabits the body of respected scientist Dr. Emilio Lizardo. The whole thing feels like the middle installment of a massive 10-episode Saturday matinee serial, which is exactly what Richter and Rauch were going for—an extended fictional universe that simultaneously manages to play it straight and send itself up.

As a movie, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension is the tip of an iceberg that exists primarily in the febrile minds of its makers, who have since labored on Buckaroo novels, sequels, and TV series that (mostly) never got made. It lives on, too, in the hearts of fans who have kept the film and its encyclopedic lore alive on dedicated websites and Facebook groups such as Yoyodyne Propulsion Systems, named after the Lectroids’ corporate front on Earth.

More than anything, Buckaroo Banzai serves as a glittering feather in the cap of Richter, whose years in the trenches of screenwriting spanned the rise and fall of the scruffy New Hollywood era of the 1970s and the coming of the bean-counters of 21st-century franchise filmmaking. Richter—“W.D.” in onscreen credits and “Rick” to anyone who knows him—wrote a baker’s dozen of scripts from 1973 to 2005. They include the flaky road comedy Slither (1973, directed by Howard Zieff), the early-Hollywood tribute Nickelodeon (1976, directed by Peter Bogdanovich), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978, directed by Philip Kaufman)—one of the few remakes as good as, if not better than, its original—and the Robert Redford prison movie Brubaker (1980, directed by Stuart Rosenberg). Ironically, this career-long writer’s writer may end up most remembered for one of the few movies he didn’t write.

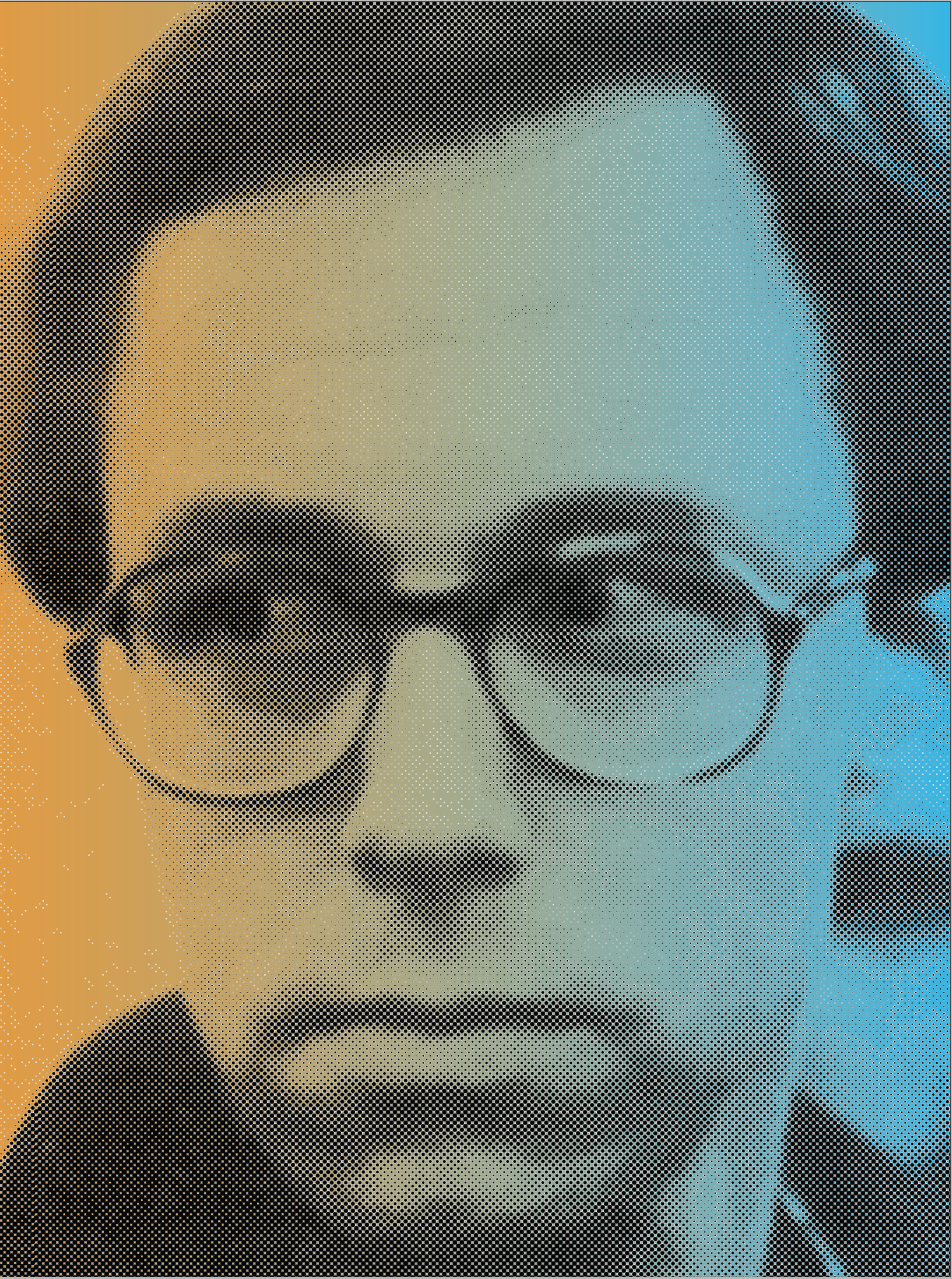

“He turned to me and said, ‘Do you want to direct it?’ And I don’t know why, but I said, ‘Sure, of course. Why not?’” That’s Richter describing the moment in 1983 when he went from the typewriter to the director’s chair at the behest of producer David Begelman—more about him in a bit. Today, Richter, 77, lives far from Hollywood, in an old stone house he and Susan, his wife of 55 years, have turned into a medieval manse atop a hill in Springfield, Vermont. Interviewed in the summer of 2023, when historic floods were ravaging nearby towns, the self-described “former screenwriter” was relieved to be situated on higher ground. That could serve as a metaphor for Richter’s years in Tinseltown, where survivors learn to keep their heads above water and maybe head for the hills when the deluge comes.

Soft-spoken and dryly funny, Richter tells Hollywood war stories that make you wonder how any movie ever gets made. His road west started at Dartmouth—he arrived on campus in 1964 from New Britain, Connecticut, “the hardware capital of the world,” on an academic scholarship and the assumption that he would continue his high school football career. A knee injury put the kibosh on that and kept him out of Vietnam in the bargain. As an English major, he took classes with newly arrived professors Alan Gaylord and Peter Saccio. He also attended Arthur Mayer’s legendary film history course and soaked up movies at the Dartmouth Film Society and the Nugget. Richter had picked up the movie-watching habit from his Polish grandmother in New Britain, who regularly took him to the old downtown film palaces, he says, “because she loved Errol Flynn.”

Graduate studies in film at USC led to an internship at Warner Brothers in the story department, reading other people’s terrible screenplays. “I came out of the Dartmouth English literature program where, whether I liked the book or not, these were real writers,” Richter recalls. “Suddenly there’s this whole underground body of literature where people couldn’t punctuate. They never made an attempt to establish a mood or anything. So I’m just reading crap, one after another, and I thought, I think I can do this, because how could I be worse?”

It was a heady time, literally, with studio executives who spent most of their time getting stoned and movies, such as Five Easy Pieces (1970), directed by Bob Rafelson ’54, that introduced an elliptical new style of film narrative. Richter’s first writing effort, Slither, made it to the screen starring James Caan as an ex-con who hits the road with a screwball Sally Kellerman at his side. It’s enjoyable despite having no plot whatsoever. And it introduced its writer to Hollywood funny money. “Slither sold for $50,000,” Richter says. “My father was making $5,000 a year at the factory, so it stunned us. I can remember literally carrying that check into a bank, like, don’t lose it.”

His next script, about the film industry’s silent era, sold for five times that much—and never got made. Instead, then-hot director Bogdanovich (The Last Picture Show, What’s Up, Doc?) had a similar idea and proposed to Richter that they scrap his screenplay and write one together. Their disastrous collaboration eventually became the poorly received Nickelodeon, with Ryan O’Neal and Burt Reynolds.

Working at Bogdanovich’s house one day, Richter had a vision of a ghost of Hollywood past while the director was out of the room. “A door that I’d assumed was a closet opened up, and Orson Welles came out in a gigantic caftan, looking straight ahead and walking really slowly. Huge. And I thought, Oh, my God, that’s Orson Welles! What’s my move? What if I startle him and he trips? ‘While you were gone, Peter, I killed Orson Welles.’ I pulled my feet under the sofa and got really low, and he just walked through and left. Peter came back, and I said, ‘Peter, I have to say, Orson Welles just walked through this room.’ He said, ‘Yeah, I’m putting him up. He’s got no money. He needs a place to stay, so he’s sleeping in that room.’ ”

Within two years, Richter was at work on the scriptfor the Body Snatchers remake, with Donald Sutherland and Brooke Adams starring and the gifted Kaufman directing. The biggest change from the original 1956 classic was relocating the action from small-town America to big-city San Francisco—an apt setting for a “Me Decade” paranoid thriller about people losing their personalities. Richter recalls that relocation as an 11th-hour decision necessitating an 11th-hour rewrite. “[Kaufman] had started scouting small towns already. And one of us said, ‘I have this terrible feeling we’re making a mistake. We don’t think of small towns as scary. Maybe Stephen King does, but we tend to think of cities as threatening and full of aliens. I mean, other cultures, not only aliens from space, but a sense of things happening right under your nose in a big city, and you could miss it completely.’ ”

It wasn’t too much later that Rauch entered Richter’s life. Despite being only three years apart at Dartmouth, the two had never met. “He may have been the guy who ripped off my frosh beanie,” Rauch says via email. “Granted, I only saw the guy running away, but he had a crazed laugh I recognized years later.”

Rauch had written a novel that Richter read about in Dartmouth Alumni Magazine and subsequently purchased. “It was hilarious,” says Richter, “so I wrote him a letter via the publisher and said, ‘I don’t know what you’re doing but I’m out here in Hollywood with people who can’t write and they’re making a lot of money, so if you have any inclination, contact me.’ ” Not long after, Richter got a phone call: Rauch had flown from Texas to Los Angeles on a whim and holed up in a seedy motel with “a monster typewriter,” ready to go.

One night, Rauch mentioned “this idea about a guy named Buckaroo Bandy,” says Richter. “He started writing it and he would give us 30 pages and we’d give him some comments. He’d come back with, I swear, 50 pages that had nothing to do with the first 30. Characters changed, plots changed. And one day he changed Bandy to Banzai. I said, ‘Wow, Buckeroo Banzai. I don’t know what it means, but I love the sound of it.’ ”

Per Rauch, the character’s germination reached all the way back to Hanover. “I was lying on the floor of a Spanish professor’s second-floor walkup on Wheelock past the gym,” he remembers. “We had been talking over a bottle of wine about John Hawkes’ new novel The Blood Oranges that she had given me to read and that I had only (continued on page 76)

gotten halfway through, so I changed the subject and asked her who was her favorite country singer. Since she was Jewish and a native Brooklynite, I figured I had her stumped, but then she said, ‘Buck Owens and the Buckaroos.’

“Somehow that conversation lingered in my head. I was also a fan of the old Gene Autry Saturday matinee serials that mixed silly sci-fi and cowboys, so that was probably the genesis of the character. From there it was just natural evolution.”

Things got crazier when David Begelman came aboard as producer under the black cloud of a late-1970s embezzlement scandal during which he’d been ousted from his position as head of Columbia Pictures and sentenced to community service. As a first-time director, Richter was already under pressure. “Directing is its own nightmare because unless you have total authority, you’re behind the eight ball all the time,” he says. “You know that you need another angle. You know you could work on the scene a little bit more. And I had been spoiled as a writer because nobody knew that I was rewriting a scene four times.”

Begelman pitched a fit when Peter Weller wore red-framed glasses in one scene because Begelman felt that “heroes don’t wear red glasses.” He hired Jordan Cronenweth, who’d done the cinematography for Blade Runner, and told him not to make the new movie look like Blade Runner. When Begelman decided it did look like Blade Runner, he sabotaged the footage by overexposing it in the lab and blaming it on Cronenweth, whom he subsequently fired. “It was really evil,” Richter recalls. On top of everything else, Weller, the movie’s star, and leading lady Ellen Barkin hated each other. “I thought I’d be able to direct some kind of nuanced performances,” says Richter. “Instead, I’m just trying to keep them from pulling each other off camera and being jerks.”

Recalls Rauch: “[Rick] somehow managed to keep his focus on the story to be told despite the vultures circling—the steady drumbeat of Begelman’s interference and the daily risk of being fired. I have to believe he was probably exhausted most of the time, but he never cracked, at least not in public…because ‘the granite of New Hampshire’…”

Looking back, Richter sighs. “It is what it is. And I’m thrilled that we did tough it out because I know it’s a special movie on its own crazy wavelength, and if I had said, ‘F*** you, David, I’m leaving,’ it wouldn’t exist.”

Buckaroo Banzai exists, and then some. It holds up and arguably makes even more sense in a popular culture drenched in conceptual prankishness and meta-absurdity. The film’s long tail of fandom has been immensely rewarding to its makers. “It really, truly, has stimulated a lot of young filmmakers and writers,” says Richter. “And I think, well, that’s what it was all about, because that’s what happened when I saw Bonnie and Clyde and Dr. Strangelove and a whole bunch of stuff like that that makes people get excited about maybe even doing some of this stuff. I know that Buckaroo has had that effect on a lot of people.”

Rauch, who still lives in Texas, is deep into writing a new novel and “rewriting an old screenplay written years ago by a stranger using my name,” he says. If you want more Buckaroo, his 2021 novel The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Against the World Crime League, Et Al: A Compendium of Evils is available on Amazon. Heads up: It’s 624 pages.

Richter lives on his Vermont hilltop, no longer seduced into flying out West for story pitches or script conferences. “I really don’t want to have five people in a room giving me notes,” he says. “And that’s the thing that wears you down, the crowd scenes. Every time I’d go [to L.A.] for a meeting, there would be three or four creative executives, and I never knew who they were or why they were in the room. I don’t know what their movie tastes are, even, and I’m supposed to be taking notes from them. It wasn’t this sort of down and dirty group of people who just love movies.”

No problem. His days are full. “I read a lot of the books that I always said I would read when I retired,” he says. “I’m on the internet a lot. No social media, just reading about architecture, design, physics, the universe. I just like to read. That comes from Dartmouth, the sense of going into Baker and the art library. I used to haunt that place because they had international magazines from all the different kinds of art going on in the world. And I kind of do that now. You find an artist you’ve never heard of, and suddenly you’re looking at four others you’ve never heard of or you’re listening to music that you didn’t know existed.

“And somehow it’s always 5 o’clock at the end of the day.”

It sounds like an ending worthy of Buckaroo Banzai himself. No matter where Rick Richter goes—there he is.

TY BURR writes Ty Burr’s Watchlist, which can be found on Substack. He previously worked for two decades as The Boston Globe’s film critic.