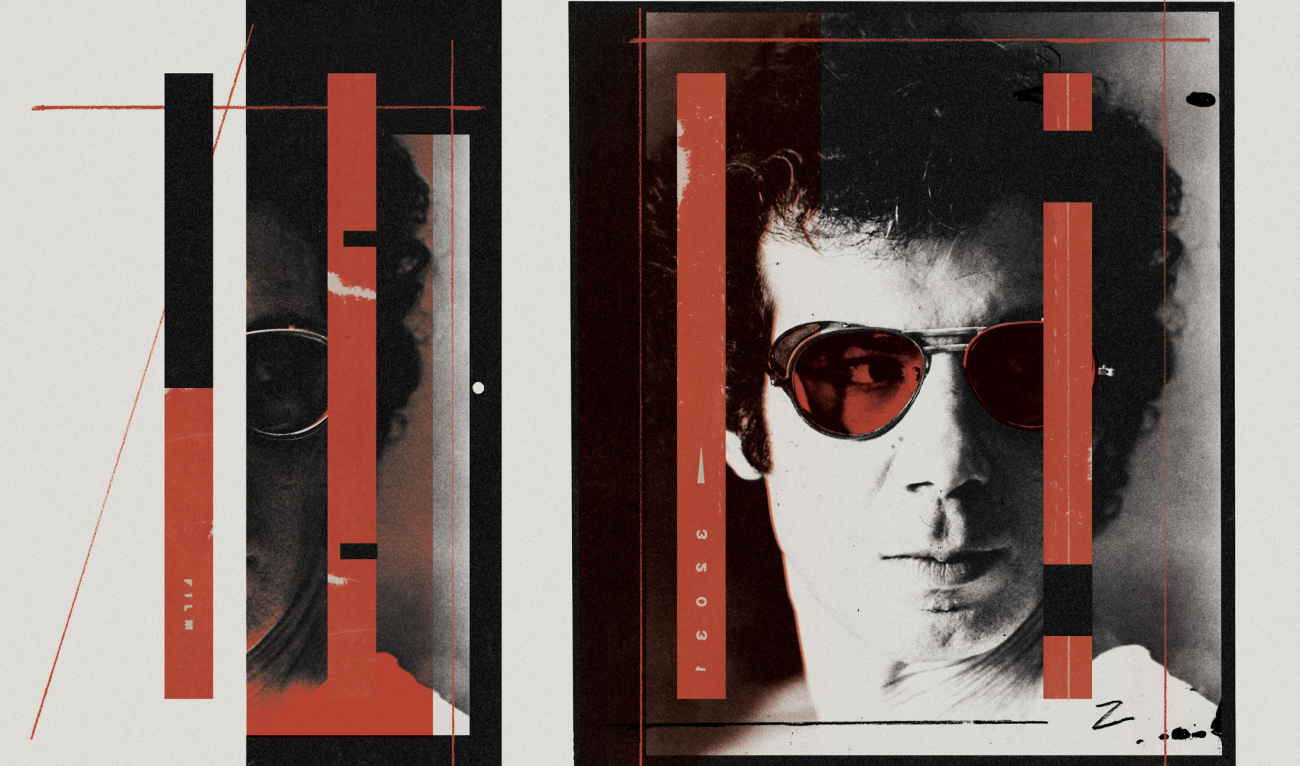

The Rebel

As he went through life, filmmaker Bob Rafelson often stopped at restaurants and diners and occasionally ordered things that weren’t on the menu. Sometimes, if he met resistance, he might get a little ornery. And sometimes a waiter, exasperated or amused, would say, “You must have seen that movie.”

To which Rafelson would reply, “Are you kidding me? I made that movie.”

“That movie” is Five Easy Pieces (1970), and its most iconic scene—a counterculture moment up there with any mid-1960s Bob Dylan lyric—features Bobby Dupea, an oil rig worker played by Jack Nicholson, trying to order a side of whole wheat toast in a roadside diner. No substitutions, says the waitress, a grim Big Mom type. Through patiently gritted teeth, Bobby proceeds to order a chicken salad sandwich on whole wheat toast—hold the chicken.

“You want me to hold the chicken?” Big Mom asks.

“I want you to hold it between your knees.”

The scene ends with Bobby dramatically sweeping the table clear of dishes and water glasses, a gesture Rafelson himself employed once or twice in his career, notably across the desk of MCA Universal studio head Lew Wasserman, at that time his boss and the most powerful man in Hollywood. Rafelson never did suffer fools or suits gladly, which was ultimately a problem, because the suits (and the fools) run the town and always will.

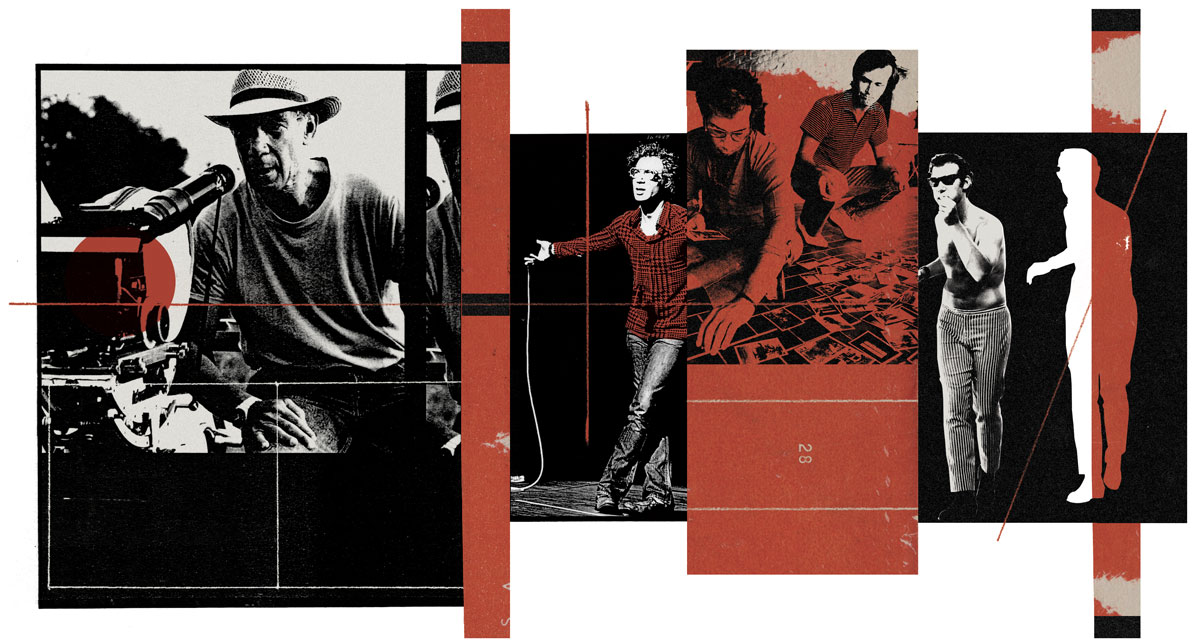

Still, it’s safe to say that during his decades in the entertainment industry, Rafelson revolutionized the movies, at least for a while. With partner Bert Schneider of Raybert Productions—later to become BBS Productions, named for the first initials of its three members, the other two being Schneider and Steve Blauner—Rafelson turned over the staid Hollywood apple cart and injected films with the rebellious fervor of 1960s youth culture. The team produced Easy Rider (1969, directed by Dennis Hopper) and The Last Picture Show (1971, directed by Peter Bogdanovich), two movies that demolished on-screen taboos about drugs, language, and nudity, proving to the studio old guard that they had no idea what was happening here.

Without Rafelson, we wouldn’t have Nicholson as we know him. Nearing 30, the actor still hadn’t broken out of B-movies and was ready to pack it in when he was befriended by the director, who told his then-wife, Toby, “I’m going to make that guy a star.” The small but crucial role of a doomed alcoholic Southern lawyer in Easy Rider brought Nicholson overnight fame when the film conquered the Cannes Film Festival. Nicholson repaid the favor by playing Bobby Dupea in the Rafelson-directed Five Easy Pieces, one of the smartest and saddest movies ever made in this country.

Oh, and did I mention that it was Rafelson and Schneider who, in the wake of the Beatles’ success with A Hard Day’s Night, came up with the idea to build a TV sitcom around an invented pop group? Hey, hey, it was The Monkees, an instant smash on both NBC and the record charts, despite cultural gatekeepers turning up their noses at the band they dubbed “The Pre-Fab Four.” “My lasting memory of Bob from those heady days,” says Micky Dolenz, the sole surviving member of the quartet, “is being in the presence of an exceptionally powerful creative force.”

The shock of all the Raybert-BBS productions is that most of it was wildly commercial, at least in the beginning. The windfall of The Monkees bankrolled Easy Rider, a movie about chopper-riding drug dealers that cost $400,000 to make and grossed $60 million globally. The Last Picture Show returned $30 million on a $1.3-million budget and was nominated for eight Oscars, winning two for supporting actors Ben Johnson and Cloris Leachman. Five Easy Pieces grossed a less spectacular $9 million but was nominated for four Academy Awards, won best picture and best director at the New York Film Critics Circle awards, and was named the best film of 1970 by Roger Ebert.

Even after BBS Productions closed shop in the mid-1970s, Rafelson, ever the maverick, could be counted on to push movie-goers’ buttons while brokering new talents. Stay Hungry, a 1976 comedy-drama about a rich kid (Jeff Bridges) fascinated with the world of bodybuilders, won unexpected critical raves for its supporting performance by an easygoing young side of beef named Arnold Schwarzenegger. Jessica Lange was an ex-model who’d starred in the 1976 version of King Kong but wasn’t taken seriously as an actress until Rafelson paired her with Nicholson in his 1981 remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice, a movie so steamy that a Russian priest the director once met swore it had sent him to the monastery.

Or so Rafelson claimed. He never let anything get in the way of a good anecdote. “Bob was a storyteller,” says Toby, a production designer. (The couple separated in 1974, divorced in 1998, and remained on friendly terms.) “He should have been a writer.…Maybe that would have taken more rejection than he cared to accept. Maybe it wasn’t glamorous enough once he got into movies. But it’s one of the things that made him so compulsively entertaining.”

A confession: This article was originally going to be an interview with Bob Rafelson. The filmmaker and I corresponded by email and text throughout the early months of 2022 without ever quite getting around to the conversation itself. At 89, he was as cantankerous and funny as ever, but he was also dealing with health problems and technological bedevilments—“I cannot use my fingers to write so I have to dictate and the bitch Siri seems to write what she wants,” he emailed at one point—and although I didn’t know it, he was in the advanced stages of lung cancer. In June, the communications went silent, and on July 23 the news came that he had died.

Rafelson put a lot of himself into his work, seeding BBS movies with bits of biography and even articles of his own clothing: The black turtleneck that Bobby Dupea wears in Five Easy Pieces was a Rafelson hand-me-down. That film’s screenplay was written by Carole Eastman, another member of the BBS social and filmmaking circle, but the story—about the scion of a family of classical musicians who rejects them for a peripatetic working-class existence—reflects Rafelson’s own ambivalence toward his well-to-do upbringing. He was born in 1933 into a prosperous milieu on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, with a businessman father in the textile industry and an educational pipeline that led him, along with other upper-middle-class Jewish kids of his time and place, from Hunter Elementary to Horace Mann High School, then to Trinity-Pawling boarding school and on to college.

Already, the movies were calling. “He wasn’t happy [at home],” says Toby, who knew her future husband as a teenager but didn’t get seriously involved with him until he was a student at Dartmouth and she was at Bennington. “He wanted to get away into his own fantasy world, which was the movies. Every afternoon he would go and spend hours. There were a couple of classic old movie palaces in his and my [New York City] neighborhood: Loew’s 83rd, the RKO 81st. There was a movie theater that ran independent and foreign films called The Thalia.”

It helped that a distant older cousin, Samson Raphaelson—old enough to be called “Uncle Samson”—was a Hollywood success story who had written the screenplay for the 1926 breakthrough talkie The Jazz Singer and nine scripts for legendary 1930s director Ernst Lubitsch. The two would go see movies together, Raphaelson and Rafelson, and then argue over their merits. By the time Bob arrived in Hanover in the fall of 1950, he had acquired the air of an independent spirit with a dash of undergraduate pretensions. When Toby next saw him, he was part of the regular Friday night storming of the Bennington campus by Dartmouth men. (“Every week, we were just invaded by these hordes of ruffians,” she says. “Boys at that age are kind of assholes. They all wore white bucks, and it wasn’t their fault, that was the fashion. But they’d be all over the campus like white on rice.”) Yet already Bob stood out, according to Toby: “He had a black turtleneck sweater on and jeans, and he kind of looked like a French beatnik.”

By all accounts, Rafelson maintained a status at Dartmouth as an outsider by choice, majoring in philosophy, hosting a college radio program, never joining a fraternity, and living off campus with two older friends, one of whom, Buck Henry ’52, would go on to a storied career as a screenwriter and actor-comedian. (When I interviewed Henry for this magazine in 2013, he recalled how Rafelson helped launch his career: “It was Bob who got me out of improvisational theater in the Village and sent me to do my first real job, which was writing and performing for Steve Allen.”) Rafelson helmed the Dartmouth Quarterly literary magazine at one point and traveled to Cornish, New Hampshire, to try to talk J.D. Salinger into becoming the College’s writer-in-residence. That went about as well as you might imagine.

Rafelson’s literary endeavors at Dartmouth caused a stir from the start: A short story he wrote about killing his (fictional) grandfather had him bounced from a freshman composition class and remanded to remedial writing. Twenty-two years later, that same story became the opening monologue for Nicholson’s character, a reclusive radio broadcaster, in 1972’s The King of Marvin Gardens, a Five Easy Pieces follow-up that was received coolly upon its release. It has since achieved the status of an autumnal classic on the strength of performances by Nicholson and Bruce Dern as battling brothers (and perhaps the two sides of Rafelson, the intellect and the con man) and Ellen Burstyn as a fading beauty.

By his senior year, Rafelson had written a prize-winning student play, but upon graduating in 1954, he returned to Manhattan and sold ties at Saks Fifth Avenue, doing everything he could to avoid going into his father’s textile business. A stint in the Army took him to Japan as a broadcaster for the military’s Far East Network, during which he and Toby—who followed and married him in 1955—steeped themselves in the groundbreaking films of Japanese masters Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi, and Yasujiro Ozu, the last having a major influence on Rafelson’s contemplative, observant cinematic style.

Back in New York City, Rafelson found a job as a script editor with producer David Susskind and shared lunches in the park with Schneider, a young TV executive; the two would gripe about the hidebound state of the entertainment industry. They ultimately decided that the problem wasn’t the lack of fresh, creative talent but, rather, the lack of producers with the ability to recognize that talent. On that premise, and a year or two later in Los Angeles, Raybert Productions was born.

The Monkees became their first calling card—Rafelson always said he got the idea well before the Beatles arrived, based on adventures he had had during a summer touring as part of a jazz trio in Mexico—but after two seasons, he and new friend Nicholson decided to kill the golden goose with the 1968 Monkees feature film (and Rafelson directorial debut) Head, so named because they wanted their next film to be promoted as “From the people who gave you Head.” That’s the story, anyway.

Aggressively surreal and decidedly of its drug-fueled era, Head includes cameos by everyone from boxer Sonny Liston to avant-garde rocker Frank Zappa. The Monkees play dandruff in the hair of a gigantic Victor Mature. Nicholson’s screenplay intercuts screaming concert audiences with footage of Vietnam War carnage. Not surprisingly, the film was a box office flop—available on DVD, it remains an audacious and rewarding artifact today—but it showed that Rafelson had absorbed the lessons of all those foreign films he’d been mainlining since adolescence and was ready to use them to remake Hollywood.

And so he did, along with fellow rebels Hopper, Bogdanovich, Francis Ford Coppola, Hal Ashby, and others. To be part of the New Hollywood generation rewriting American film grammar while partying until dawn was a heady experience. To witness it as a child was both dazzling and alarming. Says Peter Rafelson, Bob and Toby’s son, “One of my earliest memories was going downstairs and telling the Beatles and Bob Dylan to please be quiet because I had to go to school in the morning.…[My dad] certainly was present, but not so much as a father. He sat me on his knees at age 9 and had me smoke marijuana in front of all of his friends. I thought that was great while it was happening, but on hindsight, maybe not the best of fatherly practices. But he was truly an adventurer in life, and there was never a dull moment, period.”

For a time, Rafelson cut the cloth of Hollywood to fit himself and his restless generation, an act as radical as it remains rare.

As a director, Rafelson remains the hardest to pin down of his storied generation, in part because he made the fewest movies. Before The Postman Always Rings Twice, the director plunged into research for the 1980 Robert Redford prison movie Brubaker but was fired 10 days into production after allegedly punching a meddlesome studio executive on the set. By then, the pendulum had swung from the brooding, open-ended cinematic style pioneered by BBS back (continued on page 78) toward commercial blockbusters. Rafelson saw it coming: In the summer of 1975, he took the cast of Stay Hungry—Bridges, Schwarzenegger, and Sally Field—to see a new hit film called Jaws. “This is the death of the movie you’re in right now,” he told them. He was right.

In the years to come, Rafelson showed he could play the game with the 1987 thriller Black Widow, a decent box office hit. It didn’t take. He made an epic labor of love with Mountains of the Moon (1990), about 19th-century British explorers Richard Burton and John Speke searching for the source of the Nile. It’s probably the great lost Rafelson movie, but while the reviews were there, audiences weren’t. Four more features followed in the next decade, including two more with his old friend Nicholson—the one to catch is the acid-etched 1996 crime drama Blood and Wine—and then he retired to Aspen, Colorado, with his second wife, Gaby, and their two sons.

“Bob was not pushed out of Hollywood,” Gaby now says. “He really couldn’t be pushed by anyone but himself.” Determined to do better by his sons this time, he traveled with them around the world, plunged into local politics to keep Aspen from rapid growth, and held court at wide-ranging family meals during which every subject was ripe for discussion except one. “He would forbid our boys from talking about movies at the dinner table,” says Gaby. Peter Rafelson agrees: “He was sort of adamant about sheltering [my half-brothers] from the industry. But then, very much toward the end of his life, he started talking to them and going the other way.”

In his final years, Rafelson would turn up at film festival panels and on YouTube to tell his stories to a new generation. He was a world-class raconteur. After all the raucous highs and frustrating lows, it may have been his truest talent. But underneath all the tales, tall and otherwise, was an outlook on the human experience that was as sorrowful and dissatisfied and open-ended as the famous final shot from Five Easy Pieces, Bobby Dupea disappearing into an endless America into which he’ll never fit. For a time, Rafelson cut the cloth of Hollywood to fit himself and his restless generation, an act as radical as it remains rare. And when Hollywood changed its style, he went off and suited himself instead.

Greatest Hits

Other directors have longer filmographies, but few have proved as influential as Rafelson. Most of the titles below are available on demand. The BBS films (Head through Stay Hungry) can be had in a nice Criterion boxed set with loads of commentaries and other extras.

The Monkees (1966-68) An act of inspired marketing or astounding cynicism (why not both?), Rafelson and Bert Schneider’s first outing as Raybert Productions struck gold. Who cared that Davy, Micky, Mike, and Peter didn’t write their own songs or even play their own instruments? Well, they did, but the kids watching this tuneful, defiantly silly sitcom didn’t. The show’s episodes are hard to find on DVD but frequently pop up on YouTube.

Head (1968) Rafelson’s directing debut remains audacious for its sheer chutzpah. Most 1960s pop groups cashed in with a feature film; Rafelson and screenwriterJack Nicholson chose to destroy what they’d created instead. Among the pieces of this surrealist crazy-quilt are parodies of several different film genres, mostly because the director wasn’t sure he’d ever get a chance to make another movie.

Easy Rider (1969) and The Last Picture Show (1971) Rafelson didn’t direct them, but they wouldn’t exist—and movie history would be very different—without his production choices, which include getting Nicholson cast in a small but star-making role and rolling the dice on a little-known writer-director named Peter Bogdanovich. Rider has dated, Picture Show hasn’t, and both remain essential 20th-century documents.

Five Easy Pieces (1970) One of Jack Nicholson’s three greatest performances (The Last Detail and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest are the other two), this catches the counterculture generation at the crest of disenchantment. The diner scene is the one everyone knows, but Bobby’s confession to his silent, stroke-ridden father is the killer, and, oh, that final shot.

The King of Marvin Gardens (1972) A downbeat tale of two brothers, one a shy intellectual (Nicholson) and the other (Bruce Dern) a gladhanding blowhard, and a deal that may or may not go down in a decrepit, pre-gambling Atlantic City. Nicholson and Dern switched roles a day or two into rehearsals; feel free to argue with the decision. But there’s no arguing with Ellen Burstyn’s performance as a beauty queen past her prime.

Stay Hungry (1976) A comedy-drama set in and around the bodybuilding world. The last of the BBS Rafelson productions is shambling and funny and made just before Jaws changed the rules forever. It’s very much of a piece with the two movies above it on this list and maybe one of the most relaxed things Arnold Schwarzenegger has ever done.

Mountains of the Moon (1990) The odd movie out in the Rafelson filmography—a period piece about two British explorers searching for the source of the Nile—was by all accounts the closest to its maker’s heart, and production and distribution woes beyond Rafelson’s control may have taken the spirit out of him. “[He and I] both agreed that Mountains was his most powerful and captured Bob’s spirit of adventure and complexities of relationships,” says his widow, Gaby. “He was most proud of that underrated film.”

Blood and Wine (1996) Late in the day, a burst of gnarly, blood-spattered life. Nicholson, reuniting with his old director friend, plays a bastard of a wine merchant masterminding a diamond heist with a tubercular safecracker played by an almost unrecognizable Michael Caine. The cast of this tough little cookie—a tribute to the crime fiction of Chandler, Hammett, and Cain—includes a young Jennifer Lopez on the cusp of fame.

“Bob Rafelson tells the real story of how The Monkees originated” (2021) If you want a real sense of Rafelson the raconteur, dial up this eight-minute interview segment that treats the birth of the Pre-Fab Four as the punchline of a long and winding shaggy-dog story. Available on YouTube.

“Bob Rafelson Interview in Lapland” (2000) A far-ranging, frank, and often very funny hour-long interview from the stage of Finland’s Midnight Sun Film Festival, Rafelson spins stories from across the decades for a delighted audience. It’s like going to dinner with that uncle your mom warned you about. Available on YouTube.

Ty Burr writes “Ty Burr’s Watchlist,” which can be found on Substack. He previously worked for two decades as The Boston Globe’s film critic.