Driving out of Lewistown, Montana, the traditional fire danger sign unexpectedly points to “Low.”

“That arrow’s broken,” Ali Fox laughs ruefully as she sets a course for the PN Ranch along the Missouri River, 55 miles to the north. Drought arrived in the high plains of eastern Montana in early 2021, and by March of 2022 the situation was dire. Winter brought little snow, and instead of the greening promise of spring, the plains stretch brown and yellow in every direction. “The drought is bad, and really hard on our neighbors,” she says. “And hard on us for our bison herd.”

Last year local ranchers trucked in hay from as far as the Midwest to feed their cattle. Some sold their herds, and if the drought doesn’t break, more selloffs are expected.

More signs pop up along the road: “Save the Cowboy,” they shout. “Stop the American Prairie Reserve.”

Fox could take it all personally. This is a hard landscape that challenges inhabitants from every direction. Yet, somehow, American Prairie (AP)—the conservation organization Fox heads—gets targeted as the existential threat. “This is not an anti-cowboy project at all,” she says of AP’s efforts. “It’s not an anti-cow project. It’s not an anti-agriculture project.” For all the trouble this pushback has caused, Fox talks about it without frustration or rancor, instead looking to the future: “I see the opportunity to just continue to engage in the community and be more present and be more communicative, be transparent. And build relationships.”

“You need to inspire people to believe that they can make an impact with their dollars and their networks and their voice and their choices.”

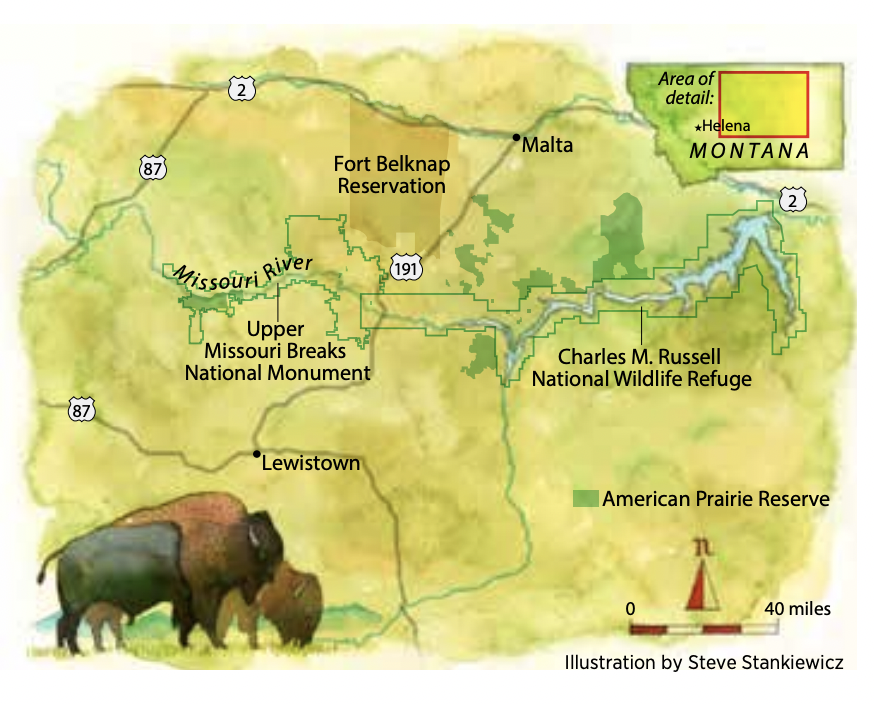

AP’s goal is to connect 5,000 square miles of this rugged territory into a thumbnail sketch of the Great Plains, a vast ecosystem that once covered about one-third of the United States and harbored bison by the tens of millions. Just 1.5 percent of this historic area is protected—in the nation that invented national parks—and none of that land is large enough to allow it to behave like a prairie. Creating and preserving such a chunk is a huge task, but Fox has some idea of what that might look like. In the winter of 2009, still early in her days with AP, she was scouting locations near the Charles Russell National Wildlife Refuge with a film producer and a ranch manager. The sky was bright and blue and the prairie covered with snow. Then the trio saw hoof prints—lots and lots of hoof prints. Parking quickly, they ran up a nearby knoll and, looking down, saw between 600 and 800 pronghorn antelope walking two or three across. The line stretched nearly a mile, a scene straight from the journals of Lewis and Clark.

“Yes, these big migratory movements still happen out here,” she realized. It was more than a photo opportunity. A herd that large was an idea, an artifact of what was, and a promise of what could be again on the prairie.

A child of outdoorsy parents, Fox grew up Ali Piper in Lower Waterford, Vermont, along the upper reaches of the Connecticut River. Her family spent a lot of time outside, hiking and visiting parks during family vacations. She had a familiar Dartmouth experience, flowing from a first-year seminar on flappers, feminism, and film into a history degree. During her junior summer, she worked at a lodge in Glacier National Park and fell in love—with a photographer, Jeff Fox, who is now her husband, and with Big Sky country. “I did not appreciate the scale of the public lands out here until that summer,” she recalls. “I decided that no matter what I did in my life, place and landscape were going to drive my decision making. I was going to go build my life around where I wanted to be. And where I wanted to be was Montana.”

After graduation Fox moved to Bozeman and met a classmate she hadn’t known on campus—Sarah Myers Pingree ’02—who was working for AP. Ali and Jeff worked a season in the Tetons and later backpacked for four months through South America. She earned an M.B.A. at Georgetown, married Fox, and together they backpacked for three months through all 11 Western states. In 2007 they returned to Bozeman. Ali sat down for an informal interview with AP founder Sean Gerrity, whom she’d met casually through Pingree. He wasn’t looking for new employees, but he made room for Fox after noting her enthusiasm, intelligence, and tremendous curiosity. He also sensed a certain kind of ambition. “I know exactly the kind of people I want to hire,” he says. “She was one of them.” He hired her in 2007.

Fox had no conservation experience but knew that she wanted a job she found meaningful. “I live in the West because of its abundance of public lands and recreational opportunities,” she says. AP was exploring an innovative mission on that landscape. “It’s this enormous legacy project.”

AP had emerged from years of strategizing by environmentalists about how to address the unique conservation challenges of the Great Plains. In the early years of the country, settlers had plowed the prairie and removed the bison, leveling a vast grassland ecosystem in just a few decades. Once the bison were gone, populations of 24 species collapsed in the northern part of the region before naturalists even had the chance to observe them. Also gone: the vast prairie root system and its prodigious capacity to store carbon.

A 1999 white paper by the Nature Conservancy suggested—and the World Wildlife Fund concurred—buying up ranchland. The arid cattle ranching region of eastern Montana was high value because most settlers chose ranching over farming, leaving unbroken sod valuable for its biodiversity.

In 2001, soon after Gerrity first learned about this hidden grassland treasure, he adopted a prairie conservation plan audacious in scale and political complexity: Stitch together 5,000 square miles, an area half again as large as Yellowstone National Park, by connecting the millions of acres in the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument with private land and state and federal grazing leases. (One square mile equals 640 acres.) The Indian reservations that bookend the area—Rocky Boy, Fort Belknap, and Fort Peck—would provide additional opportunity for conservation and connection. Biologists calculated that such a swath of land would be big enough for self-sustaining populations of native wildlife with big migration patterns. It could also support predators such as grizzly bears and wolves.

In 2004 Gerrity’s new nonprofit began acquiring land with an initial purchase of 21,507 acres (less than 0.6 percent of the overall target). By 2005 AP had pastured its first 16 bison. The year Fox joined the team, AP’s assets topped $10 million, and it collected more than $6 million in donations.

Fox was charged with soliciting lapsed donors and after some trepidation embraced the assignment. Raising money played to the tangible nature of AP’s mission. Buying a ranch or restoring a prairie dog town was more concrete than “preserving biodiversity” or “sequestering carbon,” even though it also did both of those things. “You need to inspire people to believe that they can make an impact with their dollars and their networks and their voice and their choices,” Fox says.

When Gerrity began thinking about succession, he started bringing Fox to board meetings and she stretched her skill set further. The board, then headed by major donor Gib Myers ’64, a venture capitalist (and Pingree’s father), was among those impressed by Fox. Covid emerged early in her tenure, and despite a projected 30-percent decline in revenue, Fox smoothly cleared the hurdle. “She just gets things done,” Myers says. “We have to deal with the politics that are all around us, and Alison is wonderful at that.”

Fox became president in 2017 and, upon Gerrity’s retirement, CEO in 2018. As she took command, the road got rougher.

Fox passes the last—and some of the largest—“Save the Cowboy” signs, and the road finally descends toward the river and onto the PN property, acquired by AP in 2016.

Narratives churn here, where the Judith River joins the Missouri. Lewis and Clark’s expedition camped here. The first dinosaur bone found in North America was unearthed here. Home to military outposts and treaty ceremonies, it was also an early gateway for commerce on the Missouri River. When AP purchased this land the Save the Cowboy campaign roared to life, piggybacking on lingering resistance to the 2001 designation of the national monument by President Bill Clinton. Signs sprouted, and hundreds of landowners filed deed restrictions to keep bison off their property. Bison restoration has always been contentious, but the state legislature and the governor have erected further policy obstacles.

AP built two guest huts near the rivers, but Fox has a farther destination in mind and sets the vehicle to climb, navigating an undulating dirt road up a gentle valley and back to the plateau above the river. Driving into the property her deepening relationship with the prairie animates her. She pauses amid a prairie dog town. “They’re really entertaining,” she says. “I’ve been known to take a lawn chair and a glass of wine and just watch the prairie dogs.”

She talks about the quiet beauty of running on the early morning prairie, about the crazy mud known as gumbo, and the terror of winter driving in sudden whiteout conditions. Then there’s the energy and excitement of her two young sons where there’s not much need for recreational infrastructure such as trails. “You can explore like you would snorkel in the ocean, without a destination in mind,” says Fox. “Slowly, just focusing, looking down, and wandering.”

Fox is always game for some land snorkeling, but today she wants to show off the view. Hiking up through sagebrush and shortgrass prairie, she reaches the crest of a short, steep hill and stops. As a runner she’s not breathing hard, but the view is breathtaking. Far below, the green ribbon of the Missouri meanders past cliffs and cottonwood lowlands.

Fox never seems to lose sight of why she’s here, of her love for this landscape. But the vista is also a to-do list. AP now owns 118,371 acres and controls the leasing rights on another 334,817 state and federal acres. (Because the lease land is often surrounded by private lands, AP’s purchases have also unlocked 69,000 acres previously closed to public access.) There are too many variables in play to make bold pronouncements, but the general sense is AP is about a sixth of the way to its goal.

“How do you create a collaboratively managed public-private partnership,” she asks, “knowing that American Prairie will be the smallest landowner at a table, owning hundreds of thousands of acres with the BLM [U.S. Bureau of Land Management] having a million and a half acres and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service having a million acres? Then a state agency overseeing all of the wildlife management?”

Partnerships are key. Neighboring reservations share the overall goal of restoring bison and other ecological natives. AP also has allied with the National Wildlife Federation, National Geographic, and the research arm of the Smithsonian. It even has a permanent Washington, D.C., employee to help facilitate its relationships there.

As the collective conscience of America rises around the climate crisis, the extinction crisis, and the extent to which these are related, the larger value of AP may be as a model for the future. “Large landscape conservation has to be part of the solution,” says Fox. “To save species, we need to save large landscapes. To have clean water and air, we need to save large landscapes.”

Erik Ness is a science and environmental writer. He lives in Madison, Wisconsin.

American Prairie was featured on 60 Minutes on October 23. Watch the clip here.