On October 27, 1956, the football team played at Harvard Stadium, where a gigantic “D” had been burned a few nights before on the 50-yard line. The arsonists had not been caught. The Beantown press was furious. No one was hurt. Some grass was singed and replaced. Life went on.

Fifty-four years later, at my 50th reunion in Hanover, President Jim Kim addressed our class at lunch and asked, “Who did it?” No one stood to say, “Mea culpa.” I sat, uncharacteristically silent, puzzling over statutes of limitations and definitions of arson, and wondered if the College could revoke letters of admission and inscrutable Latin diplomas. I glanced around the room for lawyers in three-piece suits with attaché cases and writs of attachment for the cost of sod at the 50-yard line in 1956 dollars. President Kim went on to other subjects.

At our 60th reunion, it was time to fess up—for my classmate Bob Hatch ’60, Tu’62, my twin brother Ed, who had then been a freshman at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) in Durham, and myself. We did it.

I cannot say why we did it or why I had remained silent in 2010 or why we finally came clean. But burning the D in Harvard Stadium was so brazen and unexpected that no one could really recall a week later—and certainly not more than six decades later—that Harvard won the game, 28-21. Everyone remembered the phantom arsonists.

Bob’s girlfriend was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he planned to go, but he needed a ride. I offered him one if he would help me burn a D on Harvard’s 50-yard line a few nights before the game. I had a car near my home in Manchester, New Hampshire. It sounded like fun. The deal was struck, and hitchhiking to Manchester was easy-peasy in those days.

Like many aspects of this entire undertaking, Ed’s involvement is puzzling. That night, in the second month of his first year in college, he and two other guys were performing jazz at a fraternity party at UNH. He recalls that Bob and I simply appeared shortly after 11 p.m. and explained our mission. He packed up his gear, and we proceeded south. Game on.

Looking back, I wonder why we expected Ed would go with us. Our motivation was dubious, but Ed was even more improbable. I asked him recently, and he simply explained that he knew I hated Harvard. Also, the fact that we had five gallons of gasoline and some green paint in the trunk of the car led him to believe we were well-organized. At this point, perhaps it is necessary to mention that, strangely, none of us had been drinking.

Ed recalls that we got to the stadium around 1 or 2 in the morning. As criminal defendants who were my clients would tell me years later, when carrying dangerous materials—weapons, narcotics, or incendiaries—one should stay within the speed limit. I did.

Gasoline is heavy, but we were young and our adrenaline flowed as freely as petrol.

We drove slowly around the stadium and found a parking lot with a chain-link fence 6 feet high. In later years, I’m sure Harvard has added concertina wire, bottle shards, motion-activated AK-47s on drones, and electrification. But that night, one of us went over the fence, one straddled the fence, and one passed up the cans of gasoline—piece of cake.

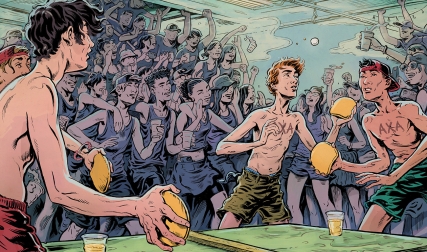

It took only a few minutes to get up and over and onto the field. We toted the cans to the 50-yard line. Gasoline is heavy, but we were young and our adrenaline flowed as freely as petrol. We took turns pouring, covering a good deal of the area around the middle of the 50-yard line in the shape of a D. It was a really big D.

Though we were beginning to sweat, it was a chilly night—time for a fire. Bob recalls he set up a cardboard box with candles while Ed and I painted green Ds in the stands. I had brought a box of Ohio blue-tip matches but spilled them when I opened the box. I picked up a match. It was damp. I picked up another and tossed it after it struck, but I missed. Bob, like the corporate executive he would later become, took over, dropped a flaming match onto the candles, and everything lit up.

Everything. It was a really big fire.

I remember being struck by how quickly the stadium went from inky dark to brilliant orange. It was so bright it looked as though someone had turned on the overhead game lights—or just ignited five gallons of gasoline. We stood back to watch, but not for long.

When someone said, “I hear voices,” I had the good sense to shout, “Run!”

We sprinted for the fence, illuminated in the bright orange glow and casting long flickering shadows as we ran. We hit the fence as a unit, went up and over in a heartbeat, I fumbled for the keys for a nanosecond, and we were outta there.

An hour or so later, we dropped Ed back at his dorm. A fine autumn dawn illuminated the blazing foliage as Bob and I drove back to Hanover.

That Saturday Bob sat high in the center stands for the game with his girlfriend, whose father—his future father-in-law—was on the field as one of the Harvard team’s trainers. The grounds crew had planted sod to eliminate any trace of our Big D. The painted Ds in the stands also were gone. Bob said he never mentioned the fire to anyone that day, figuring he would have been lynched, nor did he ever tell his wife, Nancy, or his father-in-law in the years that followed. In my own family, my tale of the incident has met chiefly with puzzlement. Given my fairly normal life, a midnight raid akin to Paul Revere’s simply seems inconsistent, perhaps inconceivable. They wonder: Why?

Perhaps it is as simple as saying, we were kids, it was the football season, it seemed like fun. No harm, no foul.

Was it a good idea? Not at all. People could have been hurt. Property could have been damaged. We could have lost our scholarships. We could have been arrested. It was vandalism. The Boston columnists certainly thought so, and our parents might have agreed. As a former public defender, however, I had dealt with a rash of teenagers every spring who were arrested for boosting convertibles. My defense in court was simple: “Your Honor, they were young and in the spring of their lives.” The judges understood.

ART LaFRANCE is a retired law professor and dean who practiced corporate law and later worked as a public defender. He lives in Portland, Oregon.