Collin O’Mara was 5 when he and his mother pored over a new issue of Ranger Rick, the National Wildlife Federation’s magazine for children. “We were reading an article on butterflies about metamorphosis, symbiotic relationships, and migration,” he recalls. “We planted some milkweed in the backyard, in my mom’s garden of native plants, and in a few weeks the first monarch butterflies showed up.”

He was mesmerized as he watched the butterflies feast on nectar from the milkweed plants—flora that does double duty as the exclusive host for monarch eggs. No milkweed, no monarchs.

“It was one of those moments when what I had learned from the magazine I was seeing with my own eyes,” O’Mara says. “It sparked a lifelong interest in restoring habitat for species that are in trouble.”

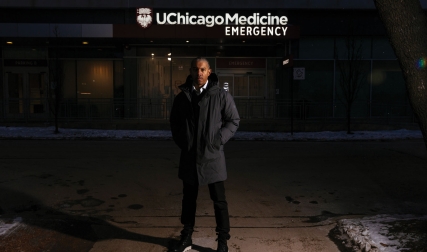

Today, 38 years later, he is still helping species in trouble and showing people they can have a direct effect on the health of the natural world. As president and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation (NWF), O’Mara leads a muscular, 86-year-old nonprofit whose 6 million-plus members and $140-million annual budget make it the nation’s largest and arguably most influential conservation organization. The federation also can call on the support of its affiliate organizations in all 50 states and three U.S. territories.

About 15 of NWF’s 373 staffers work full time on federal policy issues, supported by colleagues with expertise in science, conservation, and legal affairs. When O’Mara and his team descend on Capitol Hill to push environmental legislation, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle pay attention. “He represents an organization with significant influence here in Washington,” says U.S. Rep. Mike Simpson (R-Idaho), who has worked with O’Mara on a number of policy issues. “While the people I represent and Collin’s group are often at odds, he has proven to be thoughtful, open-minded, and solutions-oriented—rare traits in Washington these days. He is skilled at navigating the politics of D.C. and has proven many times over that groups with seemingly different goals can still collaborate and achieve important results.”

U.S. Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.) calls O’Mara an exceptional talent. “I have been in public life for 20 years, and he is one of the best thinkers, one of the best and most persuasive non-partisan coalition builders I have met,” says Coons. “He deserves a ton of credit for the impact that he has. Collin has a way of listening, reaching consensus, bringing people together, and delivering real results for conservation at a time when Washington is pretty bitterly divided and partisan.”

O’Mara characterizes his seven-year tenure as focused on returning NWF to “its bipartisan wildlife conservation, sportsmen, and affiliate roots” with a focus on “modernizing national forest management, restoring America’s waterways, improving endangered species conservation, and enhancing sportsmen experiences.” O’Mara himself is a hunter and fisherman.

In addition to lobbying for wildlife, NWF’s mission involves providing educational programming for about 15,000 schools nationwide and sponsoring a Garden for Wildlife project that has attracted 300,000 households. It publishes National Wildlife magazine, a glossy bimonthly, as well as Ranger Rick, which O’Mara’s daughters now read.

Unlike the Nature Conservancy, the NWF does not acquire and maintain real estate. Rather, it supports ongoing preservation and restoration efforts by bringing groups together and providing funds and expertise: For example, it partners with the National Audubon Society, Environmental Defense Fund, and several Louisiana preservation organizations in Restore the Mississippi River Delta, a private coalition also supported by the Walton Family Foundation.

Bipartisan is a key word in the lexicon of the NWF, whose membership is about evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats—hunters and fishermen as well as kayakers and birdwatchers, according to O’Mara, who says the organization was seen as having drifted too far to the left prior to his arrival in 2014. “It’s funny, because if you just read the paper or watch the news, you’d think there is no place where the two parties agree,” he says, “But what I have found is that, at the end of the day, we can still have conversations and talk about where there are intersections. You can still do big things. It requires a willingness to spend time with folks and find various opportunities for them to work together.”

He points to the Great American Outdoors Act, passed in 2020 and signed by then-President Trump, as proof that important things can be accomplished, even in hyper-partisan times. The NWF was on the front lines of the roughly 1,500 organizations fighting for passage of the legislation.

The bill, which received 73 votes in the U.S. Senate and 310 in the U.S. House of Representatives, fully funds the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund to the tune of $900 million annually and provides $9.5 billion during the next five years to pay for neglected maintenance of national parks.

“Collin’s optimism is a big part of what makes him such an effective leader at the NWF and beyond,” says Gina McCarthy, administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from 2013 to 2017 and now the Biden administration’s national climate advisor. “But that optimism doesn’t just apply to policy, it also applies to politics: Collin has helped find a path forward with Democrats and Republicans on important issues for our climate, such as investing in conservation, resilience, and natural solutions.”

This past fall O’Mara was back on Capitol Hill lobbying for pending legislation, including another landmark environmental bill, the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, which would fund conservation programs in all 50 states for $14 billion every decade. Previously he had persuaded the Biden administration to include an environmental jobs program for young and unemployed Americans in its Build Back Better bill, which is now on the ropes. “Decisions are made by people who show up,” he says about his frequent congressional forays.

Last year O’Mara was on the president’s short list to head the EPA. He insists he is happy where he is: “I think I can do a lot more good from within the federation, working from the outside, than I could being a cog in the wheel on the inside of the government.”

If O’Mara is playing in the big leagues today, back in 2014, when he applied to head the NWF, he was the embodiment of a long shot, a talented but little-known minor leaguer—though one who had enormous confidence in himself. Unlike candidates from national conservation organizations vying for the coveted post, O’Mara was not a biologist, a hole in his resume that he turns into a positive: “I am the beneficiary of an incredible liberal arts education. It was that multidisciplined curriculum that allows me to think three-dimensionally as we face these big global challenges now. Maybe the combination of being situated in the outdoors at Dartmouth and the multidisciplinary course of study was really transformative.”

He also had never worked for, much less led, a nongovernmental organization. He had no fundraising experience at a time when the organization was searching for someone to get it back in the black—which he since has done. Compounding that was the fact that O’Mara, then 35, was young and looked younger. He’s a fast talker, too, and some members of the search committee had to ask him to repeat what he had just said. On the other side of the ledger, he had been the youngest state cabinet official in the nation when he was tapped to head the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control in 2009—at age 29—and by all accounts he was doing a bang-up job there.

“He came in and he’s talking a mile a minute,” recalls Bruce Wallace, then a federation board member and on the search committee. “But he really read what we needed in the interview process and made suggestions. You could call it presumptuous or you could call it leadership. His ideas and his intelligence just resonated with us, and we took a chance and recommended him to the full board.”

From an early age, O’Mara and his friends were old-school, free-range kids, exploring the woods of his Syracuse, New York, suburb. “We were outside as much as possible from dawn to dusk, playing in ways that today they’d probably call social services on,” he says. “We played sports, of course, but we also did a lot of hiking, camping, fishing, just playing around in the streams.”

During his senior year at West Genesee High School in Camillus, New York, O’Mara was class salutatorian and captain of the baseball team. “I didn’t know that much about Dartmouth when I visited, but I just felt at home there,” he recalls. “A lot of it was the outdoors, being close to the Connecticut River, so close to the White Mountains. Other colleges I visited just didn’t have the same sense of place.”

He earned high honors in his major, history and classics, was a James O. Freedman Presidential scholar and was elected class president for his senior year. Now a registered Democrat, he took a semester off to work as an intern for a local Republican congressman and organized students to support U.S. Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) during his 2000 presidential bid. O’Mara spent three months in Europe, mostly in Greece, on a foreign study trip with a dozen other Dartmouth students.

Paul Christesen, professor of ancient Greek history, led the group, and he and O’Mara have stayed in touch. “Collin has ferocious energy,” says Christesen, who recalls that O’Mara’s extracurricular activities occasionally impinged on his studies. “He was deeply involved in student government and incredibly overcommitted, but not in a bad way. He is conscientious, fanatically so, to do things the right way.”

After graduation, as an AmeriCorps volunteer O’Mara taught life skills to youth who had been expelled from public schools. The following year he worked for the city of Syracuse as assistant director of management and budget. He earned a master’s as a Marshall scholar at Oxford, followed by a master’s in public administration from Syracuse University, where he ranked first in a class of 140. Then it was back to the real world: For three years he worked in the office of the mayor of San Jose, California, as a clean-tech strategist for the city’s sustainability initiatives.

“Whatever he does next, I know it will be good for the environment and good for the country.”

O’Mara’s great leap forward came in 2009, when then-Gov. Jack Markell, a Democrat, appointed him to head Delaware’s natural resources and environmental control department. As NWF would later do, Markell took a flier on the promising and energetic young man.

“It was a bit risky because that agency is among the most politically charged,” says Markell, who credits O’Mara’s five-year stewardship with helping to shift the state away from burning coal, boosting eco-tourism, and implementing statewide recycling. “He did an unbelievable amount in a short period of time,” Markell says. “Whatever he does next, I know it will be good for the environment and good for the country.”

In 2014, O’Mara met Krishanti Vignarajah, who was working as policy director for First Lady Michelle Obama. They married in 2016. An immigrant who came to this country from Sri Lanka with her parents when she was an infant, Vignarajah went on to earn a bachelor’s, a master’s, and a law degree at Yale, as well as a master’s from Oxford, and now is president and CEO of the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service. In 2018, she ran unsuccessfully for governor of Maryland.

The power couple live in Delaware and Washington, D.C., and are raising two girls—Riley, 9, from O’Mara’s first marriage, and Alana, 4. Like many modern parents, O’Mara and Vignarajah face the challenge of getting their children to play outside, away from digital devices.

“When both of them are outdoors for a few minutes, their stress goes down and any anxiety they have goes away,” O’Mara says. “We spend a lot of time hiking, and they both love to fish. They’re enrolled in a lot of sports, but we try to have some time and space that isn’t scheduled where they can get out in nature. My goal is that it becomes part of their routine as they grow.”

In a 2019 TED Talk, O’Mara addressed the importance of connecting children and grownups with the outdoors and nature. He also spoke candidly about the state of the planet that his generation is bequeathing to its progeny. He said there is 60 percent less wildlife today—from bees and bats to moose and sea turtles—than when he was born, and fully a third of all species in the United States are at risk of extinction. He prefaced the litany of alarming stats with, “I’m not trying to get you down….”

If O’Mara gets discouraged from time to time, he doesn’t let it show. He is relentlessly upbeat despite the eco-challenges ahead.

For example, on gridlock in Washington, he points out: “On the Hill relationships matter, and we spend a lot of time with folks listening to what’s important in their districts. The reality is that the outdoor economy is a huge part of many states and places that tend to be conservative, that tend to have more folks who spend time hunting and fishing, so we often try to find common ground. One of the things that I learned at Dartmouth was that focusing on the 80 percent we agree on rather than the 20 percent we disagree on is a way to make steady progress.”

For example, O’Mara has supported Simpson’s efforts to recover endangered wild salmon and steelhead in Idaho and the Pacific Northwest. “He recognizes that a solution to this very complicated issue will require us including stakeholders on all sides,” Simpson says.

For O’Mara the future is too important—and too personal—to risk letting it get mired in the political divide As he puts it, “When we save wildlife, we save ourselves.” And for anyone who argues that the cost of doing the right things will be too expensive, he points out that the cost of not doing enough will be much higher: “Our studies show for every dollar we spend on resilience, we can save $6 of disaster impact—and it is even greater if you talk about reducing emissions and getting at the root cause of climate change.”

As for the kind of world he thinks his children and grandchildren will live in 50 years from now, he says: “The world will be warmer, it likely will have more extreme weather than when we were growing up, but it will be livable. If we do our job, there will be a diversity of wildlife, we’ll avert the extinction crisis that we are barreling toward right now. The energy will be much cleaner. The waters and the grasslands and the forests will be healthier.”

The task ahead is daunting. Where to begin? One could visit the website of the NWF and click on the page titled “Milkweed for Monarchs.”

David Holahan is a freelance writer. He lives in Connecticut.