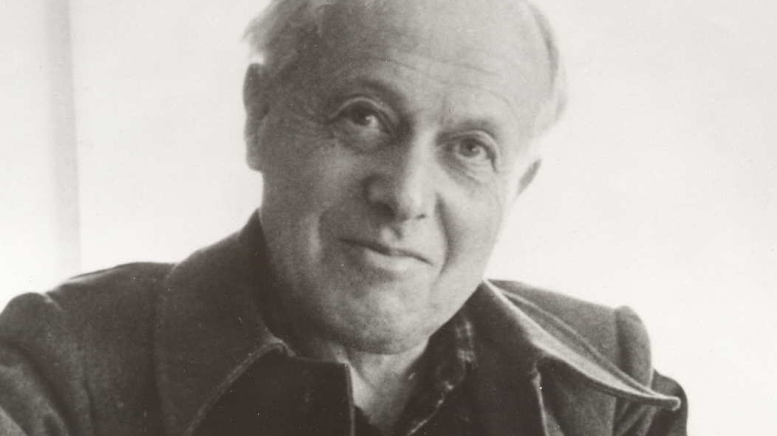

We sometimes fail to recognize the greatness of a man or a woman in our midst until years after their death. This truism may apply to professor Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy (1888-1973), a highly original thinker who taught philosophy at Dartmouth from 1935 to 1957. This occurred to me when I came upon an article in a 2013 issue of the respected German weekly der Freitag on the 40th anniversary of his death with the headline, loosely translated, “A one-man interdisciplinary warrior.” The article calls Rosenstock-Huessy a “political philosopher, historian of law, and sociologist…a boundary-crossing, universal thinker in the 20th century.”

The story notes that when the leading public intellectual in Germany, Peter Sloterdijk, accepted the prestigious Sigmund Freud Prize in 2005, he called Rosenstock-Huessy the “most important speech philosopher of the 20th century.” The article also quotes Han-Ulrich Wehler, a distinguished German historian, saying that Rosenstock-Huessy was “the only genius I have ever met.” Der Freitag goes on to summarize Rosenstock-Huessy’s life and achievements and notes that he decided to leave Germany within two days of Hitler’s elevation at the beginning of January 1933. Rosenstock-Huessy resigned his chair at the University of Breslau, foreseeing and deploring the catastrophe to come. He was in his mid-40s. He taught first at Harvard for three semesters before moving permanently to Dartmouth—from his urban perspective truly a college in the wilderness.

Rosenstock-Huessy deeply influenced hundreds of his students. Beginning in 1949 a small group of them began to record his classroom lectures out of a sense that what was being said was highly original, of imperishable importance, and needed to be preserved for posterity. Some 300 hours of Rosenstock-Huessy speaking at Dartmouth were saved, all the more valuable because he lectured entirely without notes or a script. These lectures have titles such as “Universal History,” “The Circulation of Thought,” “Comparative Religion,” and “Greek Philosophy.” On the website of the Rosenstock-Huessy Fund one can listen to these lectures and simultaneously read a transcription.

Beginning in 1949 a small group of his students began to record his classroom lectures out of a sense that what was being said was highly original, of imperishable importance, and needed to be preserved for posterity.

Societies in North America, Germany, and the Netherlands have organized to promote and study Rosenstock-Huessy’s work. Books and articles relating to him regularly appear in English, German, and other languages. In the United States, his books in English are now sold mostly by Wipf and Stock, a publisher in Eugene, Oregon, and everything is available via Amazon.

His contributions are so varied and profound, devotees of his work come at it from a half-dozen different angles. Most important is his thought on time and space as part of human experience, which he approached in a radically different way than a physicist would. He also explored the significance of human speech, including the mysteries of grammar, the fruitfulness of death, and historical change in Europe during the past two millennia. Some admirers refer to him as the most important Christian prophet of the 20th century for his work on the meaning of Christianity and on Christian-Jewish relations, exemplified famously by his major influence on the Jewish theologian Franz Rosenzweig and vice versa. This list by no means exhausts the range of his vast and insightful corpus.

If Rosenstock-Huessy is not yet in the mainstream of academic conversation, it is mostly because he was so deeply critical of the methodologies of the academic disciplines. How does one integrate the thought of a persistent critic of the ways of higher education into the study of history, sociology, linguistics, psychology, theology and philosophy? Student Page Smith ’40, a prolific historian, in his book Killing the Spirit (1990) picked up this cudgel on the professor’s behalf. Even though Rosenstock-Huessy began his career in the traditional mode, earning two degrees from Heidelberg University not long after the trauma of World War I, in which he saw mortal combat, he found much wanting in the academic world. He hoped it would eventually catch up to him in the third millennium. His most cited motto is Respondeo etsi mutabor (“I respond, although I must change”), but in his prophetic moods he also liked Audi ne moriamur (“Listen, lest we die”), which W.H. Auden quoted in “Aubade,” the poem he wrote in 1973 in memory of Rosenstock-Huessy. Auden was profoundly influenced by Rosenstock-Huessy, writing, “I have read everything by him that I could lay my hands on.”

Der Freitag thought the 40th anniversary of Rosenstock-Huessy’s death was worth noting. The 50th anniversary is coming up soon, in 2023. Rosenstock-Huessy is a renowned part of Dartmouth’s history. He taught at the College for 20 years and lived across the river in Norwich, Vermont, for nearly 40 years. The College should begin preparations for an international conference to celebrate this man and his work, which among other things bears powerfully on questions of war and peace. War, Rosenstock-Huessy said, is the natural condition of man, while peace must be created unceasingly, and he proposed practical solutions.

In the summer of 1988, the 100th anniversary of Rosenstock-Huessy’s birth, the Dartmouth campus was the site of a memorable four-day gathering with dozens of speakers, most of them former students—including Rabbi Marshall Meyer ’52, Harvard Law School professor Harold Berman ’38, and Page Smith. In 2023, few will be alive who knew him, but that kind of detachment and distance will only deepen understanding of his thought, which must endure for the sanity of the world.

The College quietly recognized him in 2010 when Rauner Library opened the Rosenstock-Huessy Archive, consisting primarily of papers donated by his family. Spanning the years roughly between 1904 and 1970, this collection includes letters between Rosenstock-Huessy and more than 500 correspondents. A priceless part of the archive are the letters that German-Jewish theologian and philosopher Franz Rosenzweig wrote to Margrit Huessy, Rosenstock-Huessy’s wife. At the time Dartmouth Jewish studies professor Susannah Heschel wrote: “The acquisition of papers of Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy and Franz Rosenzweig marks a significant achievement for the archival collections of Dartmouth College and for the Jewish studies program.…With this gift, Dartmouth…becomes a central archive for research on a crucial moment in German-Jewish thought, Christian self-understanding, and Jewish-Christian relations.”

NORMAN FIERING is a historian, author, and editor who has taught at Stanford, the College of William & Mary, and Brown University. He was the director and librarian at Brown’s John Carter Brown Library for 23 years.