Jean Hanff Korelitz had been working for two years on her ambitious new novel about a complicated Brooklyn family titled The Latecomer. But her editor, Deb Futter, told her the revised manuscript still was not ready.

“I’m going to buy this book at some point. But that point is not now,” said Futter.

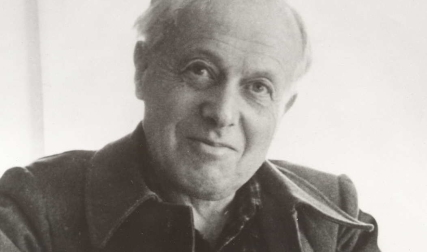

“I was so depressed and exhausted. I was so tired of this book,” Korelitz says in a Zoom call from the writing room in her 1890s house in Sharon Springs, New York. “I’m so unconfrontational, and I don’t think I’ve ever seized control of a meeting in my life.” Nevertheless, “I heard myself say to her: ‘I have another idea.’ ”

That idea was for The Plot, a novel about where ideas come from and who owns them. The protagonist, Jake Finch Bonner, a writing teacher with writer’s block, steals a plot from a (conveniently deceased) former student, rockets to literary stardom with a book aptly titled Crib—and pays a deadly price. A mystery and a horror story, The Plot is rooted, like much of Korelitz’s fiction, in a milieu she knows intimately—in this case, the publishing industry.

“She told me the plot of The Plot,” says Futter, senior vice president and co-publisher of Celadon Books. “I said, ‘That is amazing. It’s completely thought through. You can just basically start writing.’ ”

Korelitz, perennially prone to self-doubt, left the meeting relieved, thinking, “Well, at least she still wants to work with me.” The next day her agent called. “She said, ‘What the hell just happened?’ Because I had walked into that meeting unable to sell one book, and I had left having sold two.”

It took Korelitz four and a half months of nonstop work to complete The Plot (Celadon/MacMillan), which Kirkus Reviews has called “gripping and thoroughly unsettling.” Appearing this May, it is her seventh published novel. “I’m whatever the opposite of an overnight success is,” Korelitz says. “I am Jake”—except that her protagonist made a bigger splash with his first book, earning a “New & Noteworthy” mention from The New York Times.

By contrast, Korelitz’s career involved “an old-fashioned build,” Futter says. Her novels hit that “sweet spot between literary and commercial. That is her genius: She manages to write really smart books with literary references, and yet they have plots that you just want to race through.”

“I see a lot of Jean in her characters. They’re interesting and quirky,” says Deborah Michel ’83, a Bay Area novelist who met Korelitz senior year and has been close to her since.

Korelitz’s first bestseller, in 2014, was her fifth novel, You Should Have Known, about which you should know this: Screenwriter and producer David E. Kelley adapted it into the 2020 HBO hit limited series The Undoing, starring Nicole Kidman, Hugh Grant, and Donald Sutherland. Korelitz’s novel focuses on a therapist whose insights about relationships don’t extend to her own marriage and whose self-delusions are gradually stripped away. Kelley’s series, directed by Susanne Bier, amps up the wealth, violence, sex, profanity, and mystery, and erases the therapist’s Jewish identity.

Peter Ham ’83, a longtime friend and owner of a Princeton, New Jersey, landscape design business, asked Korelitz if she was upset by the changes. “Heck, no,” he recalls her quipping. “I got the check.”

The Undoing was Korelitz’s second experience with a less-than-faithful adaptation. Her 2009 novel Admission, about a Princeton admissions officer with a lackluster personal life and a big secret, became a 2013 Tina Fey-Paul Rudd romantic comedy. Korelitz remains friendly with the film’s screenwriter, Karen Croner, and says the set—populated by actor-writers such as Fey, Wallace Shawn, and Lily Tomlin—was unusually collegial.

“I won’t say it wasn’t difficult,” Korelitz says about seeing her work reimagined for the screen last year. “But it was more difficult the first time. The second time I knew what my role was, and my role is: I don’t have a role. The writer is not a very important person on a film set. When I was introduced to people as the author of the novel, the most common thing that I heard was, ‘Oh, there’s a novel?’ ”

You Should Have Known is laced with autobiographical detail. The therapist Grace Sachs (Fraser in the HBO series) borrows her profession from Korelitz’s mother, now 89. Grace’s husband, Jonathan, is a doctor, like Korelitz’s 94-year-old father, a gastroenterologist who retired about three years ago. The Sachs apartment, she says, replicates the Upper East Side apartment where she grew up.

The arrogance of her father’s generation of male doctors—“who had been informed that they were gods walking the earth”—influenced the character of Jonathan and a colleague known as “the turd,” Korelitz says. But the novel’s real seed was her mother’s fascination with her patients’ blind spots.

Korelitz has spent most of the pandemic in upstate New York. Her writing room’s curated clutter includes an antique Dartmouth print, “ugly but fabulous” chalkware figurines that were once carnival prizes, and a weird chandelier comprised of “demented little Barbies.” During the interview, an arm reaches in to shut the door—a cameo appearance by her husband, the poet Paul Muldoon, whom she self-deprecatingly describes as “way too smart for me.”

Dartmouth has figured in three of Korelitz’s novels. The character Heather Pratt in The Sabbathday River is a freshman dropout. Portia Nathan in Admission did a stint in Dartmouth admissions before winding up at Princeton’s admissions office (where Korelitz spent two years as an outside reader to gather background). Her portrait of Webster College and its embattled president in a 2017 novel, The Devil and Webster, draws liberally from Dartmouth’s own history.

“I just want to point out I was on the waitlist at Dartmouth,” says Korelitz. “We don’t forget. I never got over it.” She cites the famous motto of the Avis rental car company: “We’re No. 2. We try harder.”

After Dartmouth, Korelitz, still an aspiring poet, studied English literature at the University of Cambridge’s Clare College. While there, she encountered a Kenyon Review article in which the poet Donald Hall skewered M.F.A. programs for churning out too many “McPoets” writing “McPoems.” Claiming that the onslaught made it too hard to discover the next poetic genius, he suggested, in her words: “Those of you who are not Keats, please shut up.”

“I didn’t stop writing poetry right away,” Korelitz says. In 1990, “I actually published a book of poems,” The Properties of Breath. “But I knew I wasn’t Keats. And then I met my husband—and he was Keats.”

Born to working-class parents in Northern Ireland, he was a prodigy, legendarily championed by the Irish poet Seamus Heaney when Muldoon was just 16. He later taught at the University of Oxford, won the Pulitzer Prize, spent a decade as poetry editor of The New Yorker, and is now a humanities professor at Princeton. He is also the lyricist for the band Rogue Oliphant.

Korelitz met Muldoon at a poetry reading in London, where she had him sign one of his collections. “He has no memory of this at all,” she says. About six months later, she attended a five-day Arvon Foundation workshop that he was co-teaching. It was held at the former home of the poet Ted Hughes, in Yorkshire, with her idol, Sylvia Plath, buried nearby. “I think the writing was on the wall after that,” she says.

She moved to Belfast to live with Muldoon, and “we’ve been together ever since.” Married in 1987 after returning to the East Coast, they have two children.

There is no doubt that her husband’s gifts were a factor in Korelitz’s swerve away from poetry: “I could see that he had the passion and the scholarship and the ambition and the talent. I had an affinity with language, which is not the same thing, and deep down I really wanted to write a novel. Eventually, I was brave enough to try and fail.”

Korelitz’s first two novels, attempts at literary fiction, were rejected everywhere. “It was just heartbreaking,” she says. “When I started out,” in the 1980s, “it was the era of Bret Easton Ellis and Jay McInerney. They were writing about being stoned in a club. I had this pretension that I was at least trying to write about the human condition.”

At that point, she says, “I made a tactical decision: I wrote a more commercial book.” The result was her first (modest) success: a 1996 legal thriller, A Jury of Her Peers (MacMillan).

One of her role models was the bestselling Scott Turow, whom she calls “one of the greatest writers of plot in the world.” Korelitz had worked for his publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, as an editorial assistant to Jonathan Galassi, now the company’s president and publisher. For a year in the late 1980s, she wrote rejection letters to authors by day and labored over her own fiction by night, she says, “writing every sentence the way I wrote a line of poetry.”

Futter had previously turned her down for an assistant’s job, and she was Galassi’s second choice, Korelitz says—another instance of getting in off the waitlist. “He hired somebody from the Midwest, and this person came to New York and saw a cockroach in his apartment and left, so I got the call,” she says. “Having grown up in New York City, I was used to cockroaches.”

After A Jury of Her Peers, Korelitz bounced around among publishers. Futter, then at Grand Central Publishing, lost a bid for The White Rose at auction. With Admission, “we were finally united,” Futter says, “as we were destined to be.”

The title of The Plot is a triple entendre, referring to the plot Jake appropriates, the plot to make him pay for the theft, and the burial plot in which one character lies. Korelitz says her only regret is that she couldn’t sneak in a fourth meaning, the notion of plotting a graph.

The book’s genesis is Korelitz’s “long-held doubt that we actually are responsible for our original ideas,” she says. “I have a fascination with plagiarism. I obviously have a fascination with liars. And, for artists, for writers, plagiarism is lying.”

Her protagonist encounters an obnoxious student, Evan Parker, who boasts of having an irresistible plot for his novel-in-progress. The initially skeptical Jake finds himself agreeing. While his own career flounders, he waits, in vain, for Parker to publish. The discovery that Parker has died prompts Jake to purloin the idea and fashion it into a bestseller. He’s basking in his newfound celebrity when a mysterious email arrives, accusing him of theft. So begins an anonymous campaign to invade his life and destroy his career.

Korelitz says she drew from recent literary scandals in fashioning her plot. Her protagonist’s borrowing isn’t actually a crime—and it is soon overshadowed by the book’s darker revelations. “But it still feels wrong to him,” she says, and he knows it will to others.

The Plot’s publication coincides with “the obvious post-Undoing apex of my career,” Korelitz says. But the fear of failure “is a very ‘I am Spartacus’ thing for all of us writers. We never forget the terror of sending our work out into the world,” she adds. “Even my writer friends who have done very well understand how fragile a literary career is and feel tremendous pressure to retain readers if they’ve been lucky enough to find them. So, it’s not only a case of ‘Jake, c’est moi!’—he’s all of us.”

[Click here to read Chapter One of The Plot.]

JULIA M. KLEIN, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Mother Jones, Slate, and other publications.