If he could suit up today, Reggie Williams says he would gladly take a knee as a sign of protest against racial injustice. But no way in hell will he ever let a surgeon take that knee away from him.

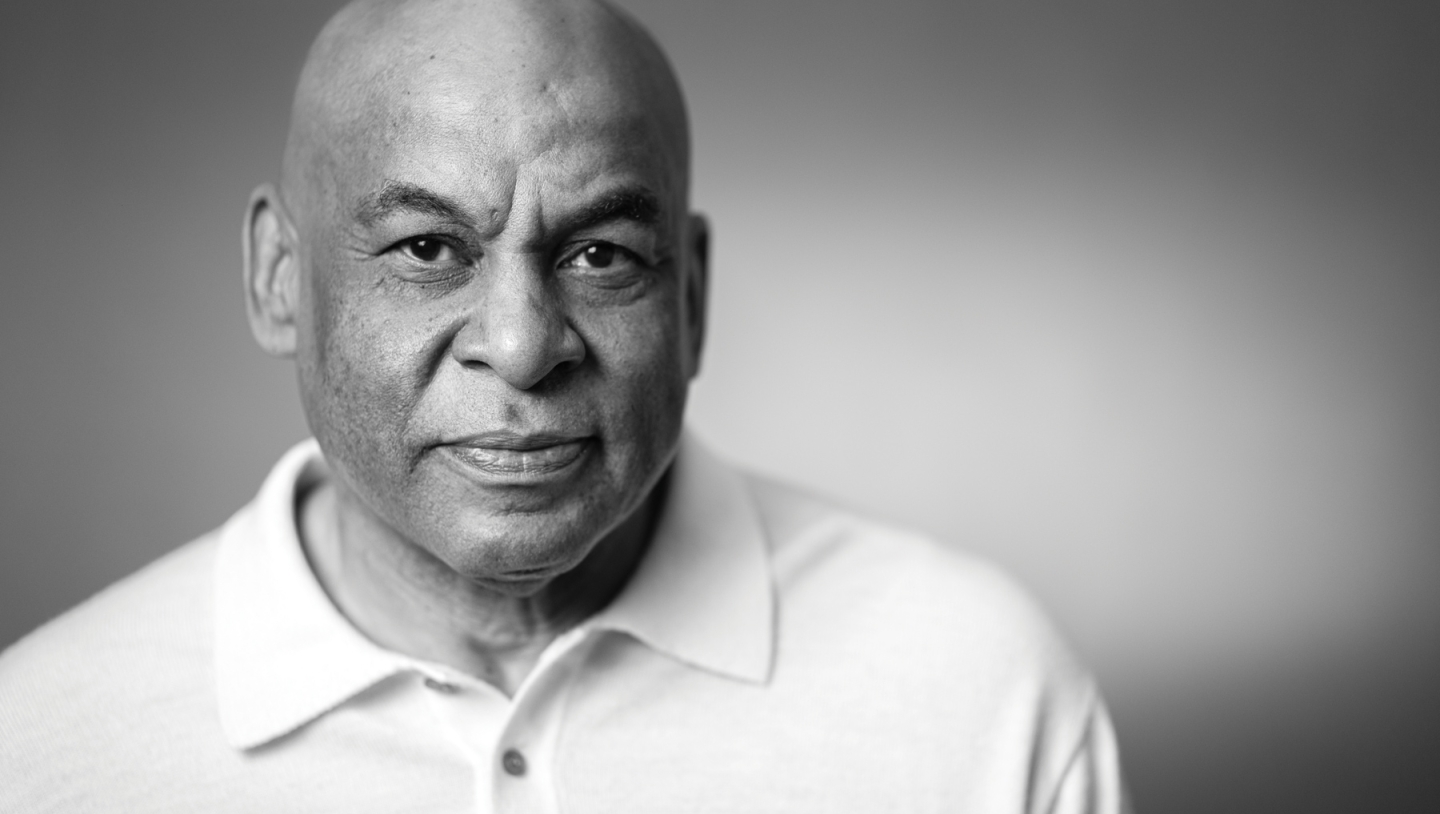

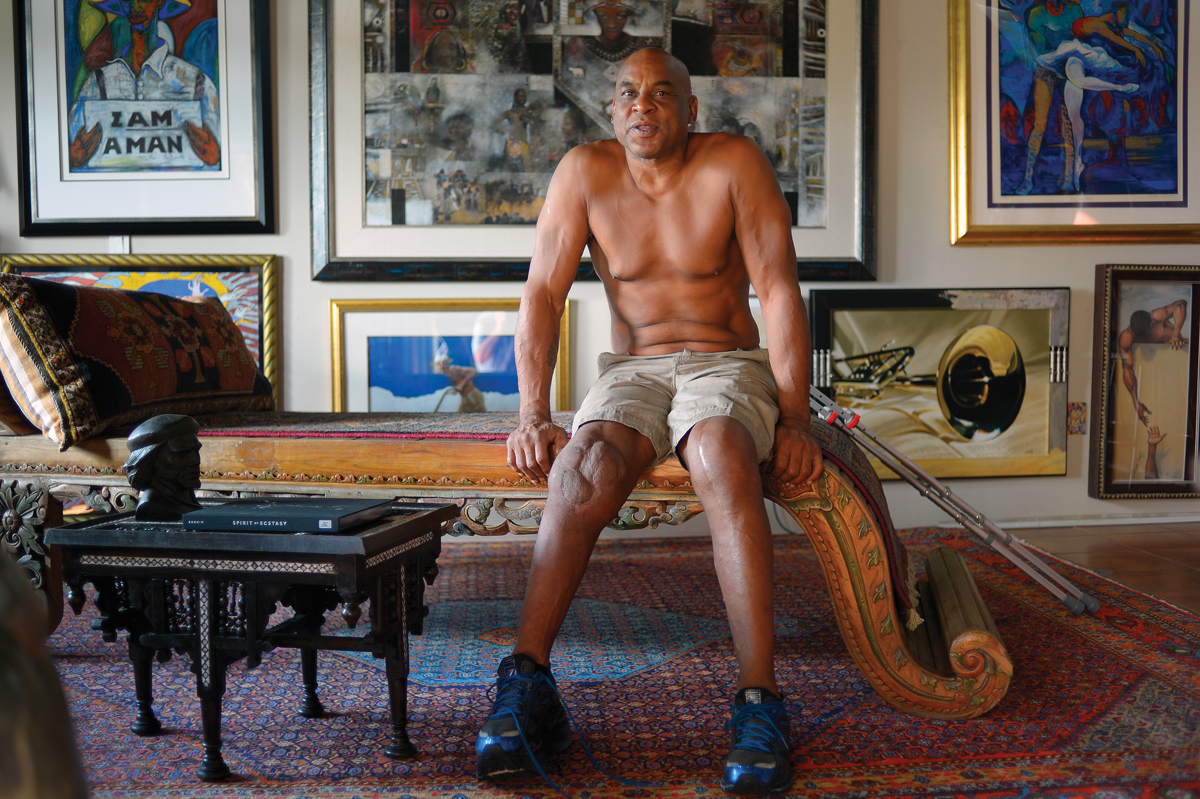

Now 66, the man whom many consider Dartmouth’s greatest football player refuses to stand down. For years doctors have advised him to have his troubled right leg removed—it is 3 inches shorter than his left because of 28 surgeries and looks like it belongs on the cover of an orthopedic medical journal. Long gone is all the hair he routinely stuffed inside a football helmet. Otherwise, Williams still looks capable of sacking the likes of Terry Bradshaw.

“I support everything the kneelings have done in terms of awareness,” says Williams, who endured 14 years in the NFL as a hard-hitting linebacker for the Cincinnati Bengals. “What Colin Kaepernick did was brilliant in the simplicity of a silent, peaceful protest. When I played I used to sing the national anthem from deep in my soul. It was like my battle cry. I could see myself singing it—and kneeling. I can easily see that.”

Williams, who can’t even bend his lumpy right knee—it’s been reconstructed and replaced four times—lives in an artfully decorated penthouse apartment in Sarasota, Florida. From here he can gaze at the Gulf of Mexico and look back on a remarkable life, one he details in his new memoir, Resilient by Nature (Post Hill Press). It’s filled with tales of awards and achievements, such as being named one of Sports Illustrated’s Sportsmen of the Year in 1987 and landing a seat on Cincinnati’s City Council one year later. It’s also full of dreams, demons, and disappointments. Some of his most vivid dreams were never realized—like the one where he wins a Super Bowl ring or the one where he gets inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Some of Williams’ most memorable dreams are terrifying, such as the one where he went to hell to save the soul of his best friend who died by suicide. Sometimes he dreams he didn’t need the aortic dissection that almost killed him in 2014 or the stroke in 2015 that temporarily left him speechless. Heck, he dreams he was never accidentally hit by a car—which has occurred on three occasions.

Then there are the dreams that came true, such as when a $100-million, all-purpose sports complex was built across 220 acres near Orlando, Florida, at Disney World. Now known as the ESPN Wide World of Sports, it is a place where hundreds of professional and amateur athletes can train and compete to fulfill dreams of their own. The complex opened under his guidance in 1997 and offers 11 softball and baseball diamonds as well as 17 outdoor multipurpose fields and three indoor arenas. Williams was particularly proud to see the NBA complete its 2019-20 season there last fall in “the bubble” during the pandemic.

“It was a long journey to convince everybody that this complex was a good idea,” says Williams, who joined Disney World as its first black executive in 1993 after working four years for the NFL. (He retired from Disney in 2007 because of leg issues.) “The business got turned down six times.”

Williams has always been a fighter. He grew up in Flint, Michigan, the son of an Alabama-born autoworker named Eli and a Puerto Rican mother, Julia. As an infant Williams was diagnosed with a hearing disorder that would affect his speech and require two surgeries to correct. On his way to kindergarten one day in 1959, he was hit by a car. In ninth grade, he says, he suffered the first of his four known concussions when he fell out of a tree while trying to impress his baby brother’s friends.

In 10th grade at Flint Southwestern, Williams wrestled and made the JV football team as an offensive lineman. A year later he made the varsity and played outside linebacker. By his senior year he was determined to go to the University of Michigan to play for legendary coach Bo Schembechler. “I was dead set on Michigan. I was sure that I would go there,” Williams recalls. “But then one day Schembechler came to my school. He said, ‘Do me a favor. If you come to Michigan, don’t come out for my team. You’re not good enough.’ He was pretty clear. He said that to my face, in front of my high school coach, Dar Christiansen. Dar is beloved by Flint and a lot of players, but he was not in my corner that day.”

“Nobody I knew from Flint was encouraging me to go to Dartmouth. I had one recruiting trip in May of 1972 and fell in love with the place.”

Williams’ college choices came down to Dartmouth and Albion, a nearby liberal arts school that wanted him to play Division III football. “I didn’t know anything about New Hampshire,” he says. “Nobody I knew from Flint was encouraging me to go to Dartmouth. I had one recruiting trip in May of 1972 and fell in love with the place. I thought of it as an adventure. A pure adventure.”

When Williams arrived in Hanover, the College was undergoing significant change. The athletic teams were no longer called the Indians. “To this day I still don’t know what a Big Green is,” he says. Also, women were admitted for the first time. Of the 150 women admitted, 29 were Black. The campus was becoming more diverse but was not without racism. At freshman football practice coach Jerry Berndt told Williams that two players from the South did not want to have their lockers near his, nor would they shower with him. Berndt responded by appointing Williams as the freshman team captain.

“It was a time of transformation,” says Williams, pounding his fist. “All of a sudden you had these white athletes who hadn’t played against or with Black athletes. Stu Simms ’72 was the first African American captain of the varsity that year. That was a significant message to the student body. We were speaking in rhythm with James Brown: ‘Say it loud—I’m Black and I’m proud.’ ”

Tyrone Byrd ’73, a senior on the 1972 team that went 7-1-1 to capture a fourth straight Ivy League title, remembers scrimmages with Williams and the freshman team. “You knew he was going to be a star,” Byrd says. “I played wide receiver and I tried to dodge him as much as I could in practice. I’d like to think I was his mentor, but nobody mentors Reggie.”

With his outgoing personality, the psychology major had no trouble making friends. In the spring of 1973 he was in the initial pledge class of the Theta Zeta chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha, Dartmouth’s first Black fraternity. Many of those friendships with his brothers have endured. “I made friends in every sport I played and every classroom I was in,” Williams says, his eyes lighting up. “My best friend was Lenny Nichols ’76. I met him on the first day of freshman football. Ken Mickens ’76, Fairfax Hackley III ’76, Steve White ’77—many of my fraternity brothers are still my best friends. Lawrence Ivey ’75 was from Cincinnati. Once I got drafted by the Bengals, we became best friends and he ultimately became my banker. I consider Tom Price ’71 a mentor and big brother and role model. Willie Bogan ’71 is one of my heroes. So proud to try to walk in his footsteps, but I never could because he was a Rhodes scholar. Grayland Crisp ’76 is a good friend of mine. Wallace Ford ’70—I have great appreciation for his leadership. There’s Tyrone Byrd and Paul Robinson ’76, who is related to Smokey Robinson. You should have heard him sing at my wedding. Harry B. Wilson ’77 was like a little brother to me. His son is the quarterback for the Seattle Seahawks.”

On the varsity as a sophomore, Williams missed the first three games because he was hit by another car. This time it happened in Flint during the summer, when a hit-and-run driver clipped him crossing the street. The resulting knee injury forced him to sit out losses to New Hampshire, Holy Cross, and Penn, but his return keyed a turnaround that resulted in a 6-3 record and the Big Green’s fifth straight Ivy championship. Williams led the team in tackles and was named to the All-Ivy and All-East teams.

“He was just lights-out one of the best football players I’ve ever seen,” says Buddy Teevens ’79, Dartmouth’s current football coach who scrimmaged against Williams as a freshman quarterback. “He was serious but had a sense of humor. The supreme compliment would be if Reggie would say, ‘A pretty good day,’ which he did to me on a couple of occasions. He was always dialed in, inspiring to everyone around him. We always talk about recruiting guys like him. He epitomizes it all.”

Williams was “the best player physically Hanover has ever seen,” says John Carney ’78, a sophomore defensive back in 1975 and now the governor of Delaware. “He was a larger-than-life super-athlete. One game, against Holy Cross, he dove over two offensive linemen, and I said, ‘Oh my God, did I just see that?’ He was big, strong, fast, and tough, but he had a gentle spirit off the field. An interesting combination.”

After the 1975 season Williams was a consensus All-American. That winter he became the Ivy League heavyweight wrestling champion and finished his studies after three and a half years. He was ready for the NFL. Gil Brandt, the Dallas Cowboys’ executive vice president of player personnel, assured Williams the Cowboys team would draft him in the first round, according to Williams.

“He wasn’t the first person to lie to me,” Williams says, “and he wasn’t the last.” The Cowboys didn’t take him, but the Bengals did—in the third round with the 82nd pick. The alternative was to play in the Canadian Football League with the Toronto Argonauts, which selected Williams in the first round of their draft.

“Those Astroturf burns, man, I still have ’em.”

Mike Brown ’57, a former Dartmouth quarterback whose family has owned the Bengals franchise since its inception in 1968, laughs when he says it was “coincidental” that Williams’ uniform number was 57, Brown’s class year. Williams had asked for 63, the same number he wore at Dartmouth as a tribute to his idol, Willie Lanier, the Kansas City Chiefs Hall of Fame linebacker. “Reggie was someone I had a special interest in since the time he came here,” says Brown, the Bengals GM since 1991. “I consider him a friend and hold him in high regard. He had a remarkable will. He wanted to achieve. He was dedicated in the weight room to make himself bigger and stronger. He dedicated himself in every way possible to be the most successful at whatever he wanted to do. That stayed with him after football as well.”

Archie Griffin, the two-time Heisman Trophy running back from Ohio State, was drafted in the first round ahead of Williams and played seven seasons with him. “He could play the game, he could play the heck out of it,” says Griffin. “I so enjoyed being around him. I loved his intensity and leadership. He was extraordinary. He was outspoken. He was never afraid to speak his mind. He’d say what he would do and he would do it.”

Williams became a Bengals starter in the third game of the 1976 season and never looked back. A tackling machine, he played 206 games for Cincinnati, mostly on rock-hard artificial surfaces. “Those Astroturf burns, man, I still have ’em,” he says. “Yeah, they got nasty during the week. It was part of the game, almost like concussions. All my knee damage came from that stuff.”

His 16 interceptions and 23 fumble recoveries are still franchise records, yet Williams never was named All-Pro or played in the Pro Bowl. He played in two Super Bowls—in 1982 and 1989—but those losses, both to the San Francisco 49ers by a combined margin of nine points, still haunt him. In the 1989 game he sat out the final five plays as Joe Montana led the 49ers to a last-second, 20-16 victory. “We were in a prevent defense and I was on the sidelines,” Williams says, shaking his head. “That’s one of my nightmares, watching my team give up all those yards. In my dream I was on the field and I made the big play. I was able to take our team to victory and I felt the warmth and love of my teammates. The hugs, the confetti were so real. But then I wake up and realize it was all a nightmare, and you have to live with the hurt.”

Hurt also would come in other nightmares. In 2008 Williams had a vivid dream in which he went to hell to save Lenny Nichols ’76, his best friend who had died in 1996. When Williams awoke, he was in a New York City hospital bed and his right leg felt as though it was on fire. “It was the worst pain I ever experienced. That was osteomyelitis,” Williams says. “It was like termites gnawing at my right leg 24 hours a day, a painful itch you cannot scratch.”

“Osteomyelitis was the worst pain I ever experienced. It was like termites gnawing at my right leg 24 hours a day, a painful itch you cannot scratch.”

Williams still cringes when he thinks about the five surgeries he had that year to save his leg. Through the years he has seen his share of titanium-rod inserts, concrete prosthetics, and skin grafts. Thanks to a specially built shoe, he can now walk unencumbered without a cane or crutches. To deal with the hurt, he has long been an advocate of cannabis. “When I was with the Bengals, there wasn’t a day I didn’t smoke weed after a game,” he says. “It was my way of dealing with the stress and anxiety of playing football. It’s a good prescription for pain.”

Williams, who suffered at least three NFL concussions, says the use of CBD (cannabidiol) patches and an occasional doobie help him deal with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which research has shown is caused by repeated blows to the head. “You really can’t identify CTE until you’re dead,” Williams says. “I had a chance to attend a lecture by Dr. [Bennet] Omalu, the doctor who was played by Will Smith in the movie Concussion, and he told me that with three concussions and 14 years of playing in the NFL, ‘You definitely have it.’ Then I took tests for two days at the University of Florida. They concluded I didn’t have CTE.”

Williams knows what he’s lost. “There are times I just lose track of conversations. Instead of trying to clarify what I’m trying to say, I’m on another train of thought all of a sudden,” he says. “The other thing that happens, in the morning, I have to get in my good cry. Every morning there is something that drives me emotionally, usually a feel-good story. On the flip side, there are certain things that make me very angry, like the loss of healthcare in any way, shape, or form. It makes me angry.”

Still, Williams looks out on the world and sees things that make him happy. The divorced father of three sons is all smiles as he looks to the future.

“I’m pain-free and looking for the love,” he says with a laugh. “I’m looking forward to seeing my grandchildren blossom. That’s what you wake up for—to see those dreams actualized. It is one of the great virtues and joys of living.”

Ralph Wimbish, a former assistant sportseditor at the New York Post, has written three books, including his most recent, Heroes: Stories of Sports, Class and Courage.