Destination: Timbuktu

John Ledyard, class of 1776, was one of America’s first celebrity adventurers and the first to be arrested and charged with spying on foreign soil. The Dartmouth legend’s mission, at the bidding of Thomas Jefferson, was to gather information on Russian commercial activities under the guise of anthropological observations, a role he took seriously. In a letter to Jefferson, Ledyard deduced correctly that America was peopled from Asia and not the other way around, contrary to prevailing views of the time. Ledyard reached the east Siberian port town of Yakutsk before his arrest and expulsion by agents of Catherine the Great in March 1788.

By June Ledyard had turned up in London and won a commission to travel to Timbuktu in Mali. It came from the African Association, a private club founded by a dozen men who wielded great influence over many spheres of British life, from government to commerce and science. Seven members were fellows of the Royal Society, eight held seats in Parliament, and most owned significant estates or controlled extensive business interests. The goal of the association, as Sir John Sinclair put it, was to “promote the cause of science and humanity; to explore the mysterious geography, to ascertain its resources, and improve the condition of that ill-fated continent.”

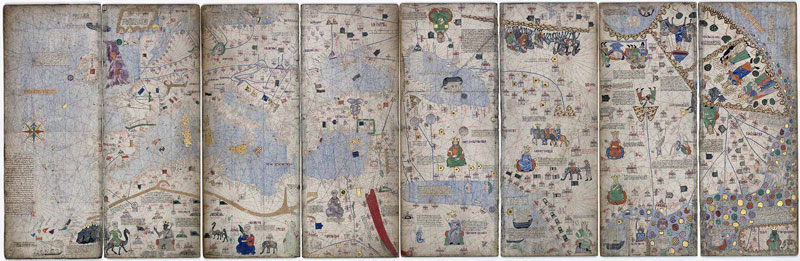

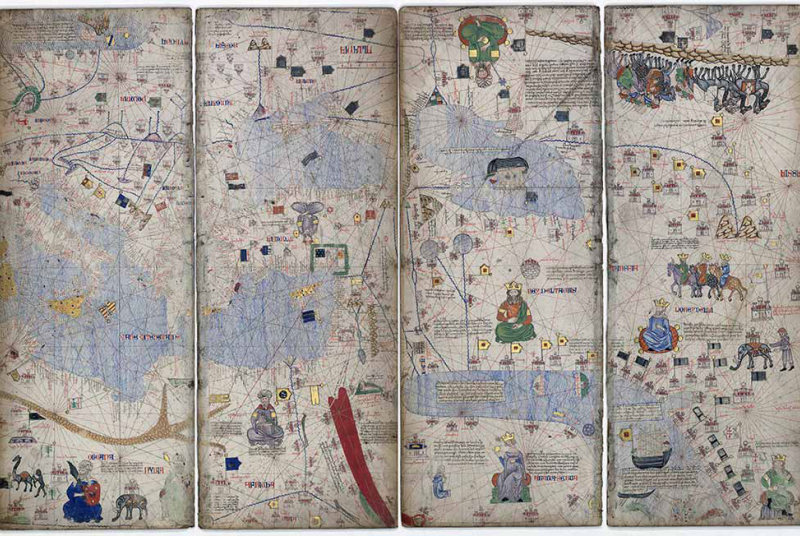

A new exhibition, “Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time,” organized by the Block Museum at Northwestern University and now on display online at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art through the end of July 2021, has renewed interest in the Catalan Atlas, a 14th-century map that led to the demise of several 18th-century explorers—including Ledyard.

Timbuktu loomed large in the imagination of the members of the African Association. In 1324 the emperor of Mali, Mansa Kankan Musa, embarked on a pilgrimage to Mecca. Eyewitnesses described an entourage of 60,000 men—his entire royal court, soldiers, entertainers, merchants, camel drivers—and 12,000 slaves, each carrying 4 pounds of gold bars, and 80 camels with loads of 50 to 300 pounds of gold dust each. Marching at the head of his procession were 500 servants, each carrying a 10.5-pound gold staff.

Musa’s largesse is now legend; he gave beggars huge ingots of gold, overpaid at bazaars, and tipped with fistfuls of gold dust. He built a new mosque every Friday and made formal charitable donations of 20,000 ounces of gold—1,250 pounds—in Cairo, Mecca, and Medina. So lavish was his generosity that his three-month stay in Cairo devalued gold for a generation, devastating the regional economy. By one estimate, Musa's pilgrimage led to $1.5 billion in economic losses across the Middle East.

Mansa Musa and the approximate location of Timbuktu were immortalized on the Catalan Atlas of 1375, which became a beacon for the African Association. The veracity of vast goldfields was thought to be all but certain, given the 16th-century descriptions of Joannes Leo Africanus, who was born al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan to an affluent Moorish family in Granada. Leo’s cartography of Africa was distinguished from its predecessors—for instance, from Roman and Greek maps, including the 2nd-century Alexandrian geographer Ptolemy—because he visited many of the places he described, including Timbuktu. His Descrittione dell’Africa, published in 1550 and translated into English as A Geographical Historie of Africa in 1600, became the preeminent authority on African geography for the next 250 years.

On the region east of Timbuktu, Leo wrote: “There is a noble river called the Niger, which beginneth Eastward from a Desert, named by the natives Seu. Others affirm that the Niger springs out of a Lake, and so goeth on Westward till it empties itself into the Sea.” This description of the Niger and its course would eventually prove fateful to Ledyard.

Several members of the African Association were active in the campaign to end slavery, yet aware of dire predictions for the future of economic growth spurred by the triangular trans-Atlantic trade network: If slavery was abolished, how would West African traders pay for British cloth and guns? The obvious answer was gold. Whether Ledyard understood these motives behind the expedition to Timbuktu or was simply an explorer for hire, he was well-equipped with courage, endurance, and the best maps available to him. What could go wrong?

Ledyard’s route was simple: He left London for Marseille on June 30, 1788, and arrived in Cairo on September 6. From there he intended to join a southbound camel caravan to Sennar, Sudan, which would become a staging point for turning westward, alone, across the Sahara to Timbuktu. Ledyard described his daring plan to Jefferson in a letter dated November 15: “I expect to cut the Continent across between the parralels [sic] of 12° and 20°N. Lat. I shall if possible write you from [Timbuktu].” Ledyard was, he said, even then “doing up his baggage for the journey.” But these are his last surviving words. He never left Cairo, falling ill instead.

Reports to London were contradictory and incomplete. Letters from George Baldwin, British consul, and Carlo Rosetti, Venetian consul, described Ledyard’s final agonizing moments. On the day of departure, Baldwin wrote, “Bad weather or other cause occasioned delay as happens to most caravans. Mr Ledyard took offence at the delay and threw himself into a violent rage with his conductors which deranged something in his system.” Rosetti said the caravan leaders felt the wind was not right. Whatever the cause, Ledyard’s temper boiled over.

“He was seized with a pain in his stomach occasioned by Bile,” wrote Rosetti. Distressed at the sudden pain, Ledyard took an emetic (acid of vitriol, or sulfuric acid) to induce vomiting. When that only worsened the pain, he followed the “incautious draught” with an even more extreme cure, tartar emetic (potassium antimony tartrate). “But he took a dose so strong,” wrote Baldwin, that his vomiting proceeded to “break a blood vessel.” Ledyard died in three days, according to Baldwin; Rosetti said six and gave a date of January 10, 1789. Ledyard was 37.

It is tempting to ask if Ledyard might have succeeded. To indulge this thought, we turn to James Rennell, the official geographer of the African Association. In 1798, he produced A Map Shewing the Progress of, Discovery & Improvement, in the Geography of North Africa. It was based on the latest intelligence and exemplifies the world view available to Ledyard 10 years earlier. On this map, Rennell marked the location of Timbuktu and the course of the Niger River, flowing eastward toward a large inland sea—which was wrong.

Yet Rennell’s position for Timbuktu was only about 300 miles off. Had Ledyard set off from Sennar and confined his journey to 12 and 20 degrees north, he would have met the Niger River, although much farther away than expected. And if he had turned upstream he would have reached Timbuktu.

Nathaniel Dominy is an anthropology professor and adjunct professor of biological sciences.