A Fan’s Notes

In 1964 or 1965, my friend Mike bequeathed to me his Boston Globe paper route. I was 11 or 12, growing up in Chelmsford, Massachusetts. My favorite remembrance of the route, even including the puppy who followed me home and stayed 17 years, is splitting duty each morning with my brother, Kevin. The experience fostered brotherhood, and, to boot, it made the enterprise feasible in winter snow drifts.

There were ancillary benefits to the job, not least of which was the opportunity to read the paper. Throughout high school the Globe offered me news and perhaps, it being the 1960s, my political persuasions. The Globe also served to buttress my loyalties to Boston, the Sox, and, weirdly enough, Harvard. Kevin and I were public school kids who, if and when we went to college, would represent our family’s “first generation.” In 1968 we became Harvard boys. That was when the Crimson football team went unbeaten, “winning” over Yale, 29-29, by coming back from a 16-point deficit in 42 nutty seconds at darkening Harvard Stadium. During the lead up to the momentous game, the Globe had beat the drum thunderously, and on Saturday my ear was glued to a transistor radio as I fought through a crackle of crappy reception for Ken Coleman’s play-by-play. In 1967 we had had the Sox’s “Impossible Dream,” and now we had Harvard over Yale. It was good to be from Massachusetts.

But something happened two autumns later. I was, against heavy odds and certainly against someone’s better judgment, accepted early decision to Dartmouth.

Why had I even taken the implausible shot, when Chelmsford High’s guidance guru scoffed that I should reach no higher than Boston College: “Save your 15 bucks.” Well, on the paper route that fall, I had been reading about this tremendous team up in New Hampshire. Coached by the storied Bob Blackman, Dartmouth was killing everyone, beating the Harvards of the world by double digits, heading for a national ranking of 14.

Having learned of Dartmouth in the Globe, I asked Dad if we could drive up and see what was what. He said sure, and on a glistening day we visited Hanover. It was the first time either of us had walked a true campus, and we both fell in love. I took the shot, quoting John Lennon in the kicker of my application essay. Things worked out.

I hated Harvard instantly. Here is just how instant instantly was: Barely a month into my college experience, on October 23, 1971, the campus decamped to Cambridge, Massachusetts, in support of our footballers. On the Avon-calm banks of the Charles River, a small group of us enjoyed the inaugural “Mom’s Hall of Fame Tailgate.” My parents, having no university affiliations before I went north and Kevin enrolled across town in what is now UMass Lowell, quickly developed the passions of the initiate. Mom proudly ladled soup to my new friends wearing a hunter-green scarf bought at Marshalls.

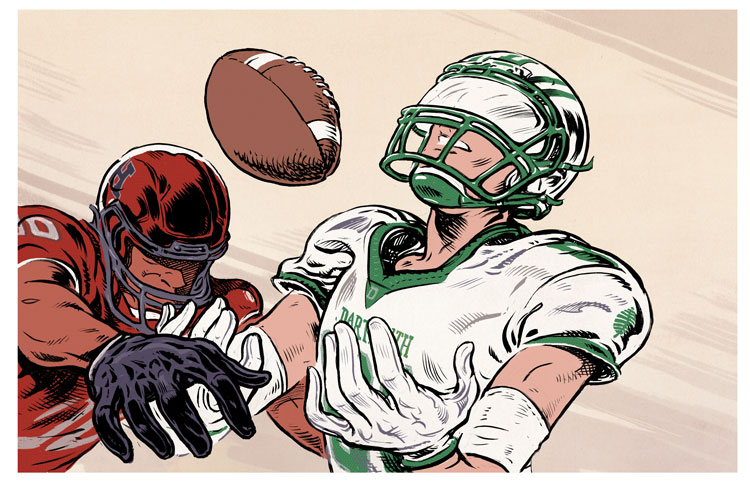

Later in the day, fortified in all sorts of ways, we of Dartmouth exulted as Ted Perry ’73 sent a 46-yard field goal just over the upstretched fingertips of a detestable Harvard defender and through the uprights, giving Dartmouth a 16-13 win. On page one of the next morning’s Sunday Globe, mine and a hundred other fuzzy faces, including that of my high school girlfriend, Nancy, would be seen in the background as, in sharp focus, the football flies through. In the aftermath of Perry’s boot, shouting turned to singing as we harmonized lustily on “Men of Dartmouth.” Our Liederkranz, comprised of pea-green freshmen, upperclassmen, and old alums, might have profited by a few alto or mezzo-soprano voices.

All that was a half-century ago, when Ivy League stadiums were often packed and game recaps might make the front pages—not the second sports page—of big-city newspapers. So much would change in the interim (not least, and pretty quickly, the constitution of our undergrad chorus). Yet many loyalties concretized that day would be forever steadfast.

A week after the Harvard game, Perry did it again in the final moments against Yale, and Dartmouth was on its way to yet another conference title. Football, which had been important to me since my first Chelmsford-Billerica Thanksgiving Day game, became more so.

And then, football found its equilibrium. As the 1970s progressed it became clear to the campus that the teams coached by Jake Crouthamel ’60, while terrific and acceptably successful (three Ivy titles during my years), weren’t quite on par with the mighty Blackman squads of the 1960s. This was, nevertheless, fine, even proper. There was President Nixon to worry about and the draft and Watergate and a divided country and civil rights and a degrading environment and our own upcoming finals and then life after Dartmouth. Also, in the many warrens of campus I had gotten to know several gods of Memorial Field as plain old friends. In Baker’s stacks and the basements of frats, these divinities were demystified. Life’s ephemera came down by notches, and then, after graduation, most all of us weren’t playing football anymore, except Kennedy-like on the lawn with our kids.

Still I remained a fan. Fidelity warms the heart like few other sentiments; there’s an especially lovely, lasting glow to its gently but firmly flickering fieriness. Regarding Dartmouth football, I would classify myself, through the years, as stalwart. My sister Gail, too, was primed to be stalwart: She followed me to Dartmouth, class of 1982, then returned for dessert at Tuck School. Kevin, our family’s ringer, mirrored our parents: As one who didn’t attend Dartmouth, he became fanatic. He would drive to Hanover, Harvard, and Yale, then lobby for rides to Princeton or Cornell. In 2018 he took in a game against Sacred Heart in Connecticut, figuring on a tilt against some kind of Georgetown or Fordham. “We beat ’em 42 to nothing,” he reported. A wasted day? Not for Kevin.

Which brings us to this past season.

Kevin and I had witnessed what can now be considered a painful prelude to the great 2019 campaign. This was the 14-9 loss at Princeton on November 3, 2018: one L on a ledger otherwise brimful of W’s. Northbound after the game, we parsed what we’d seen. We agreed Buddy’s two-QB platoon—the junior runner Jared Gerbino ’20 alternating with the sophomore passer Derek Kyler ’21—was intriguing and often effective. We lamented that some play calling in the red zone had wanted bravado. “Well,” I said, “Buddy’s smarter than I am.”

I was referencing Teevens ’79, and I here avow: I have long been a Buddy adherent. When he was playing at Dartmouth in the latter half of the 1970s, I was working in New Hampshire and saw many of his performances both on the field and on the ice. He was, of course, a tremendous QB: Ivy Player of the Year in 1978, when the team won a championship. He was equally formidable as a wing on our hockey team that finished third in the NCAAs in 1979. I met him around that time, as I recall, downstairs at Beta. Again, as I recall (you know how memories of Beta can be), he was sitting on the bar. He was very amiable. We talked of mutual friends, stuff like that. Then he became Dartmouth’s coach and won two more titles. During Buddy’s next chapter I would, on Saturday afternoons, check his progress at Tulane and Stanford on the AP ticker, which clacked away in a closet at a sports magazine where I worked in Manhattan. Then Buddy came home to Hanover. He got off to a rocky start, but “Buddy’s Glory Years III” began in 2014 and is highlighted by our 2015 and, now, 2019 Ivy crowns.

The first I saw of the 2019 team was on TV: the Penn game. I noticed Buddy’s two-QB system had a welcome wrinkle: Gerbino was a better thrower than last year. The commentator mentioned at one point that Buddy had sent Gerbino to a summer quarterback camp. Dividends had been paid, and the Penn game wasn’t even as close as the final score, 28-15.

Kevin was at the game in Hanover, of course, and reported: “These guys are exceptional.” I hoped so. I believed so a week later when we trounced Yale, 42-10. Both Kevin and Gail were at that Homecoming game, and Gail offered over the phone, “Kevin’s right. This is a tremendous team.” It was good to have her confirmation, since Kevin’s view of Dartmouth football requires scrutiny. Buddy’s boys went on to beat Marist by 42 and Columbia by 35, and I said to myself, “I’ve got to see these guys.” I received dispensation from my always-fair wife, Luci, to head for Harvard the next weekend.

On a gloriously sunny Saturday, Kevin and I took our euphemistically called seats on the fanny-punishing cement of Harvard Stadium. My brother’s constant state of great expectation—his certainty that something fantastic is bound to happen—was the only balm as we suffered through 59 minutes of pretty leaky football. Last year’s Pats’ Super Bowl has made me a defender of “defensive gems,” but what was on display at Harvard was excruciating. As the clock descended toward the final minute, we trailed, 6-3. We stopped the Crimson with a desperate goal-line stand: 60 ticks left, no timeouts, the Harvard end zone 96 yards away.

Gerbino had been dinged, so the show belonged to Kyler. Harvard was in a prevent, and Dartmouth was therefore allowed a series of plays that looked like success. But, as I said to Kevin, “We’re too much down the middle. We need a sideline to stop the clock.” I quickly added, “Of course, Buddy’s smarter than I am.” After a 22-yard strike to the fleet senior Drew Estrada ’20, the ball was on the Harvard 43 when Kyler spiked it, stopping the clock. Six seconds left.

“Hmmm,” I said to Kevin, “Frank Champi had only three seconds back in 1968.” Indeed, in the game to end all games, Harvard’s javelin thrower had only half as much time to find Vic Gatto in the far corner of the end zone. But Champi had taken the snap much closer to pay dirt, and, as we from Massachusetts know, he was in that moment touched by God.

A field goal for Dartmouth to tie was impossible from 60 yards, so Kyler dropped back. He was hit. But, maybe nudged by God, he spun free. He bought enough time for the end zone to fill with gridders Crimson and Green. He launched a high-arcing bomb. One Harvard player tipped it, then another. At last the beleaguered ball stunned our sophomore, Masaki Aerts ’21, when it nestled in his welcoming chest and embracing arms. The Harvard side of the field went stone silent, just as the Yale side had 51 years ago, just as the Harvard side had when Perry’s kick was perfect in 1971. Next came an enforced pause in our celebration as the refs checked replay. We knew the catch was fairly made. Even Harvard’s players, littered prostrate all over the field, knew it. The refs finally threw their arms aloft and allowed our festivities to recommence. The Dartmouth side of the stadium serenaded the players with “Dear Old Dartmouth,” and they gleefully saluted us back.

We knew the catch was fairly made. Even Harvard’s players, littered prostrate all over the field, knew it.

Where was Gail, whom I now texted? Believe it or not, in Hanover. A Dartmouth women’s leadership conference had been scheduled for Harvard weekend. The College’s president was up there, too, addressing the women. I guess the assumption in 2019 is that women and administrators aren’t the kind of folk who might be fond of football. Gail told me later that she and mutual friend Martha Beattie ’76 were on their phones, desperately trying to figure out what the devil was going on in Beantown, when Gail received my happy text.

Back in the moment: Kevin and I made our way out of the stadium and headed to Harvard Square, where we had arranged to meet up with Gail’s husband, Scott, at the Charles Hotel. Scott had left the game before halftime to take a stroll around Cambridge. Fair enough: The action had been less than sparkling, and he’s a Williams guy.

As Kevin and I marched forth, we drank in a sun-splashed scene: blinding foliage, a postcard campus. “Boy,” I said to Kevin as we strolled, “the square was a dump when we were kids. Look at it now!” The buildings were large and new. Coffee shops, folk clubs, and head shops had yielded to restaurants targeted at the 1-percent. Dodging our way through the nouveau square with its circuitous traffic patterns, Kevin and I found the Charles’ bustling lobby. As we waited for Scott, two strangers noticed our green garb and gave us a hail-fellow-well-met greeting.

“Good for you!” the cheerful man said. “We lost to Princeton last week, and that was brutal. I hate ’em like Yale. But this was okay. A thriller!”

“We didn’t deserve it,” I said disingenuously. “You were there?”

“Sure,” he said. “Quite an ending!”

The woman chimed in, “Do you know about Harvard beats Yale, 29-29?”

“Sure,” I said in turn. “My brother and I were talking about it earlier.” I introduced myself and Kevin. The Harvard man’s name was Jim Reynolds, and I confess I’ve forgotten his wife’s name. “Today’s finish must have been the wildest since then,” I added.

“He played in that game,” the woman said, indicating Jim. “The 29-29 win.”

“Wow,” I said. “Really?”

Jim demurred modestly, attractively.

By 2019 I felt I had at last earned dispensation to behave like an old asshole who wears a letter sweater to football games, and Jim, to keep our genial conversation going, asked, “You played football?”

“Oh no,” I said. “We were good at football when I was there. I hung onto the bottom rung of the tennis ladder.”

“Ah,” said Jim. “A friend at our club is Lloyd Ucko. I’ve never taken a set off him.”

“Lloyd!” I said as the coincidences piled on. “He was captain, three years ahead of me….”

Surely this banter with Jim could have continued and it would have turned out that Jim, Kevin, Gail, and I are distant relations if you dig deep in County Kerry, but Scott’s arrival brought an end to the powwow. “Hey,” said Jim with real meaning as he sent us on our way, “Beat Princeton! Next weekend, isn’t it? Yankee Stadium?”

“Yes,” I said, “crazy as that sounds.”

As I forced my aching knees into Scott’s car, I thought, not for the first time: Maybe I’m falling apart. Balky knees, and look at this: I no longer hate Harvard, not necessarily.

Perhaps it was because we were finally beating them again. Maybe it was the sunshine or the intercession of Jim Reynolds. I certainly didn’t hate him; in fact, I liked him. So maybe it was Jim or maybe it was recalling that game of 1968, back when Kevin and I were Harvard boys. Or maybe, after a half century of animus, I’m mellowing. Or marinating. Maybe I’ve lost whatever edge I once had.

Now, as to that last subject with Jim: Princeton vs. Dartmouth at Yankee Stadium. Yes, it did sound crazy, didn’t it?

I researched a bit, and here’s how I understand it: To the everlasting chagrin of Harvard and Yale, the first college grid game was played between the New Jersey Tigers (Princeton) and Rutgers Queensmen in New Brunswick, New Jersey, in 1869, with the Queensmen prevailing by the even-then-ridiculous score of 6-4. With the 150th anniversary of that game approaching, Princeton and Rutgers thought it would be special to play a showcase match at the new, soullessly mall-like Yankee Stadium. But Rutgers started demanding this and that and the deal collapsed. The stadium told Princeton’s coach that he could still have the yard if someone else wanted to come play. The Princeton coach phoned his buddy, Buddy, and Buddy thought Yankee Stadium was a terrific idea. Buddy is a firm believer in “life experiences” for his charges. Our College backed Buddy’s argument instantly and began promoting the porous rationale that the game was to celebrate our endlessly ongoing 250th birthday (and, in the bargain, extend our anniversary-pegged fundraising into November and into New York City, home of Monopoly money). Anyway, the pact was made and everyone was delighted. One wag in the Wall Street Journal observed that the audience at the Dartmouth-Princeton fray would be just like the one at the next day’s Jets-Giants blood match across the river in Jersey, “but with New Yorker subscriptions.”

I approached the whole shebang with apprehension. If Prince-ton wound up winning narrowly and emerged as the lone unbeaten team atop the Ivies, I, for one, would remember who was due to be the home team this season. Weren’t we surrendering an advantage? Wouldn’t Vegas consider Memorial Field worth at least three points? Yes, yes, I know: life experiences and all that. But “undefeated” would be a nice life experience, would it not?

Well, I figured finally, Buddy’s smarter than I am.

Gail and Kevin drove from Massachusetts to our house in the New York ’burbs, and the next morning I steered us to the Bronx. Despite the cold, the crowd streaming to the stadium was substantial. For the second week in a row Dartmouth was going to play before more than 20,000 spectators, and I’ll bet that hasn’t happened since I was in school.

Once ensconced in our $59 seats, it seemed to me that there was more green than orange in the stadium. The huzzah was mighty as the Green got off to a great start. I thought back to how much I, like Jim Reynolds, enjoyed beating this team. Princetonians were so This Side of Paradise preppie: snooty, straw-boatered. The Dartmouth mindset, when I was up there, seemed to regard this matchup as our Harvard-Yale: They had each other; we had Princeton. The other four Ivies each had a disqualifying quirk when it came to rivalry: Cornell could be Syracuse, Penn might as well have been in Cleveland, Brown and Columbia were intrinsically odd, urban, and horrible at football. But Princeton, like us, was an outpost Ivy on a serene campus, and neither of us was Harvard or Yale—so we had each other. I hated them once and hated them still, particularly after the 2018 result.

Our running game was effective. Our All-Ivy defensive end Niko Lalos ’20 pitched in with a 22-yard pick-six, and the whole team was riding high. Clapping our mittens vigorously, the chill didn’t exist as we darted to a 17-0 lead. There was a blip just before the half, narrowing affairs to 17-7, but during halftime, bonhomie was the rule on our side of the stands. Friends visited old friends and posed for selfies with the scoreboard as background. Then, in the second half, Gerbino got on his horse and Dartmouth pulled away to a 27-10 throttling. Princeton’s fans had long ago fled the frigid premises by the time we were harmonizing on the alma mater.

In the aftermath of the Sturm und Drang at Harvard and in New York, it seemed we were finally faced with tranquil sailing, leading inexorably and inevitably to that enchanted isle, a spotless season. Our focus turned, now, to the matter of Cornell, which led to recollections about the epic clash of my freshman year. That massively consequential 1971 contest was played in Hanover, just like the 2019 set-to would be. It, too, was on the season’s penultimate weekend.

Back then, thanks to Perry’s leg, we had squeaked by Harvard and Yale, but then had unaccountably sagged against Columbia, losing by two. Meanwhile, Cornell, riding the running of the great Ed Marinaro, was coming in unbeaten. The impending showdown was the biggest of big deals. ABC pulled into town to broadcast it, and first-team sportscaster Chris Schenkel was spotted at the Hanover Inn and other places. I had to traffic in an undergrad black market to score tickets for my parents, who drove from Massachusetts with Kevin and Gail and, stuffed in the trunk, a Lucullan tailgate. Memorial Field was in a frenzy from first second to last, as Dartmouth bottled up Marinaro and beat Cornell, 24-14.

I have to digress here for the briefest bit as I have a terrific postscript to that 1971 game. Jack Manning ’72, a senior defensive star for the good guys, sent along an email just now from his home in Missoula, Montana. In it, he remembered tackling Marinaro in the end zone near Leverone at one point. “As we got up, we were close and facing each other,” Jack wrote. “I reached out my hand, he reached back. We shook and I said, ‘I hope you win the Heisman.’ I think he said, ‘Thanks,’ and we trotted away.

“I watched the Heisman show a few months later. They showed Ed’s 46-yard-run several times, I think it was his second longest run of the year. No. 26 of Dartmouth was prominently featured in the clip. Ed and I later became good friends. He once told me that, when the show went to commercial, the host, Bud Palmer, asked him, ‘Did that Dartmouth player really shake your hand?’ Ed said, ‘Yes.’ Palmer shook his head and said, ‘Only in the Ivy League.’ ”

Isn’t that sweet? But returning to the pressing subject at hand, the 2019 game, and dismissing the sentimental hogwash Jack traffics in, I was thinking, We’re gonna kill ’em again! Dartmouth is just too good this year, and Cornell isn’t very good at all.

I don’t know what happened. Gail and I were among the multitude that didn’t weather the miserable November day. Just more than 3,000 stouter loyalists did, and of course Kevin was among them. He filed by phone: “Different team than you saw. Did everything wrong. We stunk.” Ordinarily it is my Sunday habit to decode statistics so I can envision what actually happened; box scores are my crosswords. In this instance, I skipped the exercise. It is only with an ingrained sense of reportorial responsibility that I record the score: 17-20.

So now we were tied with Yale atop the league. I was sure that Cornell represented what they call, in sports as in life, a hiccup—one of those inexplicable, isolated arguments for why we play the games. On to Brown, as dear Coach Belichick might say.

If anything, I was even more certain that we would beat Brown in the finale than I had been concerning Cornell. Why? Because Brown is Brown, and always has been. Brown is the forever safe harbor that all Ivy opponents can relievedly espy through the Rhode Island fog. With only Brown standing between us and a record 19th Ivy crown—either shared or, should Harvard summon its will against Yale, free solo—affairs still seemed in order.

Three days out the Rhode Island weather report for Eastport to Block Island predicted pleasant, and I called Gail. She said, “I’ll go if you go.” We lobbied Kevin, but he was so disappointed—disgusted, really—that he insisted he was done with the Green until next year.

There’s the difference, you see. Gail and I, as alums, are allied with the team by the science of our green-flowing blood: the immutable, inescapable fact of it. It is our pleasure but also our duty to support all things Dartmouth, especially if the climate is fair and psych profs aren’t involved. Kevin, the religious convert—the righteous (and self-righteous) zealot—is far more demanding. He owes Dartmouth nothing, Dartmouth owes him, and so he is stern. He’s also focused: focused on football and on winning. No sentimentalist, he doesn’t give a damn about Pilobolus’ new dances, the latest shows from Connie (Womack) Britton ’89 and Shonda Rimes ’91, Jake Tapper ’91 on Sunday mornings, or our Arctic researchers’ efforts to mitigate sea-ice loss. For Kevin, it’s football. And Dartmouth football’s share of the deal is to reward Kevin’s unalloyed support with victories. Kevin can’t be bothered with such Ivy-coated nonsense as competing well in the spirit of the thing. He will stick with his lads for the entire unforgiving hour, filling it with 60 minutes’ worth of distance run, but if the scoreboard reads 00:00 and says we’ve lost, then Kevin has been betrayed. With that burp against Cornell, the team let Kevin down. Kevin, in turn, now spurned the team. See you next fall, Buddy.

Regardless, I was still looking forward to Gail’s company as I drove north to Providence. The morning was as advertised: sunny and unseasonably warm for the Saturday before Thanksgiving. I met Gail on the grass of Parking Lot A, where she was socializing at a tailgate sponsored by my classmate and dear friend Killer (John Kilmartin ’75) and Killer’s wife, Glo—whom I introduced to each other nearly a half-century ago. Their spread was sumptuous, even though, since ours is no match for the “Greatest Generation,” it wasn’t a patch on Mom’s. Chris Ley ’73 and Janette were there already, as were Richie Horan ’76, Tu’80, and Gray Reisfield ’82. We all did a little catching up; everyone went lighter on the alcohol than in days of yore. Since Gray and Gail were classmates, they had news to share. We all shared, as well, analysis of that week’s Ukraine testimony and the awful acrimony dominating the public square. “Was it worse or better in the Sixties?” As at Mom’s bygone tailgates but with evolved topics, we shared opinions, personal news, and good laughs. We shared, for the first time in this particular company, talk of grandkids.

Then we headed for Brown Stadium and a noon kickoff. No one had yet mentioned the football. There were no worries about that.

There should have been. The same Dartmouth team of a week ago had apparently shown up today. Brown, with nothing to lose but the cellar, came out throwing. Their QB, E.J. Perry, was strong and on target—he’s a transfer from Boston College, where they know how to play football better than they do at Brown—and would stay hot all day. Dartmouth’s secondary bent regularly and broke occasionally in the first half, which ended with the Bruins leading, 10-7.

During intermission we strolled back to Parking Lot A for pastries. “We just haven’t got going,” I said. “No way we score only seven.” That was true, but we scored only seven more in the third quarter and entered our season’s final stanza trailing the bums, 23-14. This meant we had to score twice; a TD and a two-point conversion wouldn’t tie it. And so we would be passing. And so we would be seeing a lot of Kyler.

On the first play of the fourth quarter, Kyler was sacked, and Brown took over on downs.

Ah, but sometimes an athlete picks a fine time to put on a show. Kyler and his trustiest target, Estrada, picked the very best of times. After a Dartmouth defensive stop, Kyler went on a spree wherein he couldn’t miss, hitting 10 of 12 the rest of the way, accounting for 162 of his career-high 303 passing yards and two of his career-high four touchdowns. His final TD pass—to Estrada—covered 39 yards and put us ahead, 29-23, with time dwindling. Chris was choirmaster on Dartmouth’s perdurable mashup “As the Backs Go Tearing By” segueing into “Glory to Dartmouth.” Our gang remembered all the words, but I noticed as I scanned the stands that many greener Greeners, trying to follow Chris’ lead, seemed to be singing “As the backs dum-dum-dum-dum….Glory to Dartmouth, loyal we be! Now we’re together, make the da-da-doo-dah-Dartmouth!” Lest old traditions fail.

Brown’s son-of-a-gun Perry refused to quit, and with less than half a minute left had moved his team inside our 10. Now, however, our two great senior defenders asserted themselves: Lalos broke through for a sack and, on the next play, Isiah Swann ’20 intercepted in the end zone. The clock said 17 seconds. Start etching that trophy, my good lapidary.

Our crew’s cheerful postgame celebration was marked by smiles and smartphones, the latter for photo taking and scoreboard watching. I ceded these tasks to others because I’m just not as adept with my devices. (Much to my kids’ frustration, I’m a tedious texter, employing a single finger as I seek each lettre juste.) So it was for others to send happy pictures to absent friends, meantime searching for Yale Bowl updates. We all agreed it was the first time any of us had rooted for Harvard, although in my case I knew this not to be true: Exactly 51 years ago today, when I was yet a youth….

What was happening in New Haven, Connecticut, in 2019 was, as you might have heard, almost as historic as what transpired in 1968. This time it was Harvard that sprinted ahead, leading 15-3 at the half. At that point a platoon of students stormed ashore and staged a good old-fashioned sit-in. This was very much a shades-of-the-1960s moment, with “Stop climate change!” substituted for “Out of Vietnam” as a rallying cry. I had a few quick thoughts. Can something as esoteric as a demand for economic divestiture be as society shattering as our guns-or-butter protests of old? Where in the world did today’s kids even learn how to sit-in? Finally, I sure hope the delay hasn’t chilled that Harvard football team.

It had, apparently. Yale rallied precisely like yesteryear’s Harvard had rallied, scoring two late touchdowns to tie. The NCAA has changed its rules since 1968, and so now there would be a tie-breaker, then a second one. Yale ultimately escaped into the gloaming with a 50-43 win and half an Ivy crown.

We old alums bid one another farewell, perhaps until next season, and I drove north for a night’s stay at Gail’s before enjoying breakfast with her and the Sunday Globe’s account of the football dramas. Route 128, which always terrified Mom and Dad, wasn’t so bad tonight, so I could allow my mind to wander. Great season, I reflected. One of the best.

Which was best of all?

Well….

We can speak only from personal experience.

So, from that vantage, I would say that, maybe, the best possible situation from which to not only enjoy a championship season but also to have the experience be truly special—elevated even beyond the football itself, elevated to where it might build or deepen bonds of fellowship, elevated to one of Buddy’s life experiences—the best is probably to be a 17-year-old freshman cheering along with family and brand-new friends, the future boundless, nothing but wins at hand and ahead.

The second best, in my estimation, is to be sharing my experience with family and longtime friends as a 66-year-old veteran, thinking happily of campaigns at hand and behind.

Robert Sullivan spent the 1980s at Sports Illustrated. Among his books is Our Red Sox: A Story of Family, Friends, and Fenway. He is currently working on a sequel to Flight of the Reindeer, which debuted as a 1996 cover story in this magazine.