Professor Vincent Starzinger, a legendary and demanding Dartmouth instructor, left his most lasting impressions in the lecture hall, where he taught generations how to think about government and the U.S. Constitution.

“He was so funny and clever,” says U.S. Sen. Angus King ’66, an Independent from Maine. “He would come about 15 minutes early and write on the board the names of the people he was going to mention in the lecture. It was always first initial and last name. Like S. Ray Robinson, J. Christ, W. Churchill, H. Bogart. It was a wonderful technique. The moment you walked into the room and stared at the chalkboard you wondered how he was going to weave these names together. You were instantly curious and engaged.”

Some five decades after those classes, the senator retains passages from Starzinger’s lectures in his head.

Starzinger died last September at age 88. He had retired from teaching in 1994 after terrorizing generations of incoming freshmen in his survey class, “International Politics.” He even memorized their names before they ever plunked down in the hard, wooden chairs of 105 Dartmouth Hall.

“He was like a Shakespearean actor on stage.”

Paul Gigot ’77, The Wall Street Journal’s longtime editorial page editor, calls Starzinger “the best lecturer I’ve ever heard in any academic setting or, for that matter, any setting. The flow of logic, the humor, the storytelling, the precise diction. He was like a Shakespearean actor on stage.”

Shortly after learning of Starzinger’s passing, Gigot listened to a tape recording of one of his lectures. “It was just astonishing,” he says. “The clarity and the wit. When you heard that, you just kept coming back for more.” Which clearly was the case, because Gigot took not one, but five classes with “The Zinger.” The professor’s noted reputation for exacting toughness—the source of endless dorm room commiseration—was earned. He handed back a chapter of Gigot’s thesis with slashes through the first four and a half pages “and a little note saying, ‘Start here,’ ” says Gigot.

“Starzinger was not somebody who was contributing to grade inflation,” Gigot recalls. “He was a pretty rough guy. He was very formal. Everybody was ‘Mister’ or ‘Miss.’ And that could be forbidding because he had a very formal style. In class he was very much the instructor, and you were the student.”

Tom Barnico ’77, a Boston College law professor and longtime Massachusetts assistant attorney general, is another former student who, years after his time in Hanover, visited the Rauner Special Collections Library to listen to recordings of Starzinger lectures. “There was something about his rigor of preparation and delivery that the 20-year-old mind understood to be at the highest level,” Barnico says. “Like a great performance.”

Starzinger’s was the only class not cancelled during the great blizzard of 1978.

Starzinger came to Dartmouth in 1960. Raised in Iowa, he studied alongside Henry Kissinger and James Schlesinger at Harvard. A rugged outdoorsman, he climbed more than 200 high peaks and rowed more than 58,000 miles on the Connecticut River. The class of 1981 newsletter noted that his was the only class not cancelled during the great blizzard of 1978, when Starzinger ventured across the bridge from his home in Norwich, Vermont, on cross-country skis.

Starzinger’s demands for rigor in the classroom crossed the political spectrum. “He was not there to make you think a certain way, he was there to make you think,” says Gigot. Wayne Young ’72, a Vermont attorney, recalls how Starzinger addressed emotional debates about the Vietnam War, which could not be sidestepped when talking about government. “He respected any position that was well argued but was ruthless in exposing sloppy thinking from all sides,” Young says.

The lecture that stood out most to King used the movie The African Queen to explain different views of natural law. “Humphrey Bogart wakes up in his boat to see Katharine Hepburn dumping his gin out into the river, and he’s very upset. He says to Hepburn, ‘It’s only natural, ma’am, that a man should want to drink every now and then.’ That’s one view of natural law. Hepburn says, ‘Nature, Mr. Allnut, is what we are put in this world to rise above.’ That’s the other view of natural law. It has been 50 years, and I remember every word of that lecture.”

King wonders whether Starzinger, who published only one narrow though highly regarded book during his time at Dartmouth, might have had trouble earning tenure under today’s rigorous publish-or-perish regime. “It tells you we’re not valuing teaching enough,” he says.

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner ’83 has a similar view of Starzinger’s lasting legacy. “He made you think and made you curious,” he says. “The definition of a great teacher.”

Matthew Mosk is a senior investigative producer for ABC News. He is based in Washington, D.C.

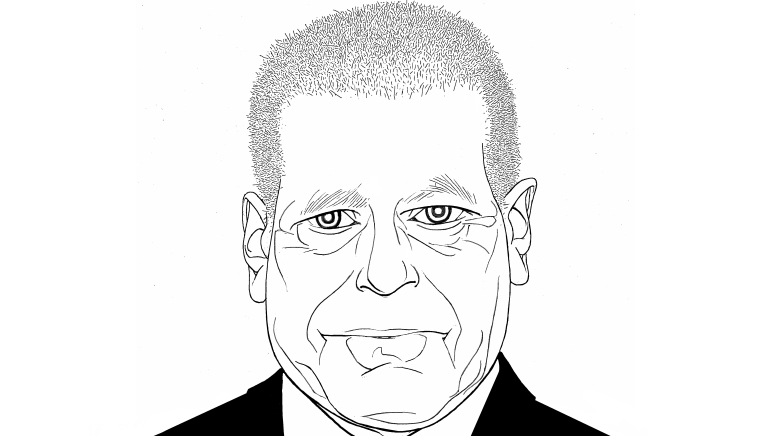

Illustration by David Johnson