It was March 7, 2015, and Rembert Browne was nervous boarding a plane. He didn’t have a fear of flying and this wasn’t a case of middle seat dread or concerns over missing a connection. He was uneasy because this was no ordinary airplane. This was Air Force One.

Browne was one of five journalists chosen to travel with President Barack Obama to Selma, Alabama, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of what became known as “Bloody Sunday,” the march for equal voting rights that led to vicious beatings of peaceful black demonstrators by police. To be part of this momentous day with the president was an honor for Browne, to be sure, but right up until takeoff, he was a wreck. “I thought, ‘There’s got to be some reason why I shouldn’t be on this plane, like there’s a bomb someone put in my bag or some weed I don’t know about, and I’m going to get arrested or thrown off,’ ” he says. “I was a mess.”

At the time Browne was a writer for ESPN’s sports and pop culture blog Grantland, where he’d built a following thanks to his unique brand of humor as well as his astute observations on bigger issues. One day he’d write a tongue-in-cheek analysis of Men Without Hats’ “Safety Dance” video, the next he was reporting from the ground amidst riots in Ferguson, Missouri, after the shooting of Michael Brown. His annual “who won the year?” brackets were also eagerly awaited, in which he’d choose winners between odd matchups such as 50 Shades of Grey author E.L. James vs. Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt, or boy bands vs. Pinterest. For site founder Bill Simmons, hiring Browne was a slam dunk.

“We loved him immediately because he could write sports and pop culture and his writing was so entertaining and accessible,” says Simmons, whose new show Any Given Wednesday with Bill Simmons airs on HBO. “He’s one of those writers who makes you feel like he’s your friend even if you’ve never met him.”

Browne’s encounter with the president was bittersweet since he’d narrowly missed getting a blogging job he’d desperately wanted with the 2012 campaign. Now he was sitting at a conference table in the sky with Obama, a man he’d admired since high school. He turned the experience into a story that was insightful and deeply personal. Seeing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in person, Browne wrote, he was reminded of “this country’s ugly past…those brave men, women, and children who risked it all so this stain on American history would be seen by all, in hopes that it would never repeat itself.”

Unable to tell anyone of the trip beforehand, Browne hitched a ride to his mom’s home outside Atlanta after the emotional day and showed her a post-flight memento. “I just saw this gold envelope and a picture of an airplane and thought, ‘Oh, no, this boy’s signed up for flying lessons,’ ” says Charlyn Harper Browne, who is a senior associate at the Center for the Study of Social Policy. She was thrilled to hear of Rembert’s adventure, and even more delighted this past February when he took her to a Ray Charles tribute at the White House. Although Charlyn is proud that her son’s accomplishments have opened doors and allowed him to meet celebrities, she’s glad he’s not the type to brag about it. He didn’t even ask for a photo with the president to blast out on his Instagram feed. “Everyone asks him for pictures,” Browne says of POTUS. “I was trying to earn a little respect. I’m very anti-selfie in moments like that.”

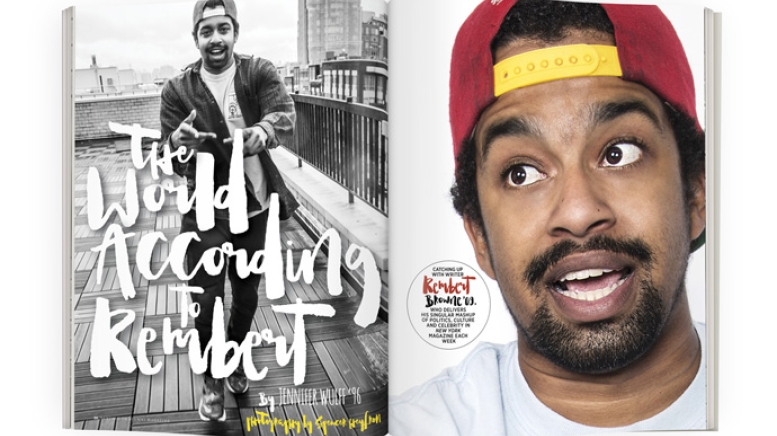

After Grantland’s demise (ESPN shut down the site last October), Browne landed a job at New York magazine, where he’s now reaching new fans as a writer-at-large. “Rembert is a voice you always want to see popping up in your news feed because he writes so smartly and humorously about culture in the very broadest sense, often bringing together politics and pop culture in his essays—comparing Kanye West and Donald Trump, for instance, or using Hillary [Clinton] and Macklemore to make a point about white privilege,” says executive editor Lauren Kern.

On a Saturday afternoon at a small bar near his Brooklyn apartment, Browne, in flip flops and a faded shirt with “Hanover” in white type on the front, is a bit groggy as he orders a beer and a Cuban sandwich. He’s still recovering from a late night with friends. He’s just woken up from a nap following a viewing of the first half of ESPN’s eight-hour O.J. Simpson documentary at the Tribeca Film Festival that morning. “I showed up like this with a McDonald’s hash brown in my hand,” says Browne. “They were like, ‘Wow, thanks for dressing up.’ ”

The writer, who made this year’s Forbes 30 Under 30 list, wears a similar ensemble for an appearance the next morning on NBC’s Sunday Today with Willie Geist. While his fellow guests on the panel could go straight from Rockefeller Plaza to a job interview at Goldman Sachs, Browne looks like he’s just returned from a camping trip.

“One of my forms of activism is choosing what I write about, and one of my purposes in being a writer is societal good.”

Since joining the New York staff, he’s being asked to do more TV appearances and attend more events, but the fame game isn’t one he’s eager to play. The magazine’s head publicist says he turns down about half the media appearance requests she fields. “I have a hard time thinking of myself as a brand,” says the 29-year-old, who has also been a guest on MSNBC’s All In with Chris Hayes and Comedy Central’s The Nightly Show with Larry Wilmore. In primary season he was also a co-moderator at Iowa’s Brown & Black Presidential Forum, where he asked Bernie Sanders how he could really provide free college education and asked Clinton if she thinks white domestic terrorism is as grave a threat as ISIS. (He wore a jacket for that event—with red Nike high tops.)

In fact, setting up an interview for DAM was a challenge. I received no response when I emailed Browne at the two accounts I had for him. No reply to messages left at his work number either. I joined his 116,000 followers on Twitter and as a Hail Mary sent a tweet his way. “I’m in” was all I got. He finally texted me but didn’t answer in return, and when I called, it went straight to voicemail—which, of course, was full. How do millennials handle dating? I thought, grateful to have dodged that generational bullet.

When we do finally meet, I give him a hard time for being so elusive. “I’m sorry. It’s not cute, I know,” he says, smirking and pulling his hoodie around his face. “I live in this fantasy world where I think everyone knows what I’m doing and I can’t understand why they don’t know I just want to write and be left alone.”

High school friend Parker Smith says that those closest to Browne are used to him being hard to pin down. “Every time I see him it’s like an awesome surprise,” says Smith, who wasn’t sure if Browne was going to honor his RSVP to Smith’s Alpharetta, Georgia, wedding in April until he saw him. “You never know if Rembert is going to show up or not—he’s just this magical human being who appears.”

Part of Browne’s reason for not making plans is that he likes to live in the moment. But he is often simply so immersed in his work that all else falls by the wayside. “It’s a whole thing when I write,” says Browne, who works from home or the bar where we met and is disciplined about not going online or texting while putting together a story. “I get all my procrastination stuff out of my system before 9 a.m., and then I don’t do it for the rest of the day.”

Although he still uses Twitter and Instagram and Facebook, mostly to post links to his latest story or kill time while his pieces are edited, he says he’s over earlier addictive tendencies. “I used to refresh my Twitter feed every five minutes,” he says. “Social media is like drugs. I’ve gone through the whole cycle. Now I just let my phone die sometimes, and it’s amazing.”

Browne learned to write at Dartmouth, by way of the epic Sig Ep party emails he sent campus-wide. “I’d sit through an entire class and write a 700-word email about a dumb party on Friday. My whole goal was to be funny enough to convince people to come drink and dance. That’s the origin of my writing career,” he says.

The publisher of The D at the time was a friend and convinced Browne to put some of that creative energy into his own column, where he riffed on topics such as the College’s decision to buy a huge TV for the Collis Food Court and conducted irreverent interviews with safety and security officers. As vice president of his class and a freshman trip leader (some may recall his rainbow hairdo), the sociology major became a campus celebrity. “He had one of the biggest social networks I’d ever seen. He seemed to know everyone—students, staff—and they all knew him,” says sociology professor and now vice provost Denise Anthony, who was his advisor. With his thesis, “Upper-Class Black Identity and Social Distancing,” and in his work since, she praises his gift of “saying something important while also making you smile or even laugh out loud.”

“I felt like my truest self at Dartmouth,” says Browne, who fell in love with the College on Dimensions weekend.

“He came home with the biggest grin on his face,” says his mother. “A lot of people were surprised I ‘let him’ go to such a predominately white school, but if I fought him it would have been World War III. And I was delighted. I knew he’d flourish there.”

In fact, when Browne suffered a rare case of writer’s block last January, it was Dartmouth that got his mojo back. He called up a pal who’s now at Tuck and asked to crash on his couch for a week. “I really just needed to write at Baker for 12 hours a day,” he says. Dartmouth will always be close to his heart. He may not reply to a lot of emails, he says, but he does answer those he gets from students asking for career advice. “At a certain point I won’t be able to pull it off,” he says. “But as long as I can be accessible, I’ll do it.”

Browne, who interned on Capitol Hill for Sen. Ted Kennedy in 2007, praises the increase in political activism on campus since his time in Hanover. “I think the average 18-year-old is a lot less indifferent than when I was 18,” he says. “The country is in turmoil and people want to express their anger and frustrations.”

While he’s attended two “Black Lives Matter” marches himself and felt moved by the experience, “that’s not really my forte, marching and protesting,” he says. “As a professional, I don’t think that’s where my strength is. One of my forms of activism is choosing what I write about, and one of my purposes in being a writer is societal good.”

For Browne’s mother, who was 37 when he was born, giving her son the best education possible was always her top priority. He had his first exposure to the classroom sitting on her lap at Georgia State University while she took courses toward a second Ph.D. (She had already earned one doctorate in early childhood education after a B.A. in psychology from Spelman and a master’s in educational psychology from Atlanta University.) When she later taught in the evenings at Atlanta Metropolitan State College, he listened as intently as her students. She recalls him as a curious child with a sharp memory who loved reading, music and tennis and was also very funny. “We always had a great time together,” she says. “He was an absolute delight to parent.”

After her divorce from Rembert’s father when Rembert was 6, Charlyn was the primary parent. (His father died in 2001.) She sent him to a local Montessori school through fourth grade, then chose to enroll him in one of Atlanta’s top private schools, Paideia, which, though mostly white, “wasn’t going to beat the black out of him,” she says. “It was important to me that he not lose his racial and ethnic identity.”

That occasionally meant teaching his instructors about black culture, as when one day in fifth grade all the kids were asked to show up in tie-dyed peace and love gear as part of a lesson on the late 1960s. “I said, ‘Wait a minute, your dad and I weren’t hippies,’” says Charlyn. “So I got a dashiki out of his closet and bought the biggest Afro wig I could find and a ‘black power’ Afro pick and that’s how he went to school. I knew he was at the right place when the teachers came out to thank me for reminding them about diversity.”

When Browne graduated from Dartmouth it was the height of the recession, and he soon learned that a job offer he’d accepted at Time Out New York had been downgraded to an unpaid internship. He enrolled instead in the urban planning graduate program at Columbia, but his heart wasn’t in it. To get through the drudgery he started a blog called 500 Days Asunder, where his goal was to post something every day until he got his degree. Perhaps as a result of spending more time on his blog than his studies, he failed an economics class and had to take it again in his second year. “I walked in the first day and felt like the entire class of first years was looking at me and then I walked back out,” he says. “I just couldn’t do it.”

By that point, an editor at the newly formed Grantland had stumbled upon Browne’s Tumblr page and given him some freelance work. Soon there was a fulltime job offer, and Browne took it, dropping out of Columbia with no regrets.

With assignments that took him to the NBA All-Star game and festivals such as Coachella and South by Southwest, Browne reveled in his new role and always went the extra mile, sometimes literally. When his editors suggested a one-month road trip called “Rembert Explains America,” he upped it to three months and covered 43 states, filing a story every day of his often-lonely journey. “He really grew as a writer on that trip,” says Simmons, who later gave Browne his own podcast, Rembert Explains.

Browne, who wrote for Grantland for four years, is still close with his former boss and mentor. And Simmons would add him back to his roster in a second. “You know those parents who still think their kids are coming home even after they graduate college? And they keep their bedroom exactly the same just in case they ever want to move home? That’s me,” says Simmons, whose new website is called The Ringer. “If Rem started working with us again it wouldn’t even feel like we hired him. It would just feel like he moved back to his old room and nothing changed. He’s like family and he’s always going to be like family.”

For now Browne is trying to maintain a balance between covering day-to-day culture and delving into heavier issues. “I make a very conscious decision to sometimes write about some super-heavy shit about the state of the world and then on Monday write about a music video. People contain multitudes,” he says, paraphrasing Walt Whitman. “And I don’t want to get lumped into writing just about race relations because, suddenly, that’s all you’re doing.”

Referring to himself as a “liberal hippy dude,” Browne is concerned about the current tone of hostility in the nation. “The hate thing drives me nuts,” he says. While he leans to the left, he’s more angry at those who refuse to have a dialogue than those with opposing beliefs. “I do tend to operate in a world where I believe things should be a certain way, but that doesn’t mean there’s another side that can’t be argued. But many people are really uncomfortable with what they’re not experienced with. And they’re stubborn. Still, I’m an eternal optimist, and I have to hope things are going to improve.”

And should they not, Browne may just try his hand at politics. Not that you’ll see him at any podiums—just on the teleprompter. “I’m fascinated by speechwriting,” he says. “To be that far behind the scenes, you disappear. It’s weird that that’s the direction that makes me the most excited, but it’s my dream: To be where no one knows who I am, but my words are so important.”

Jennifer Wulff is a former staff writer for People and a contributing editor to DAM.