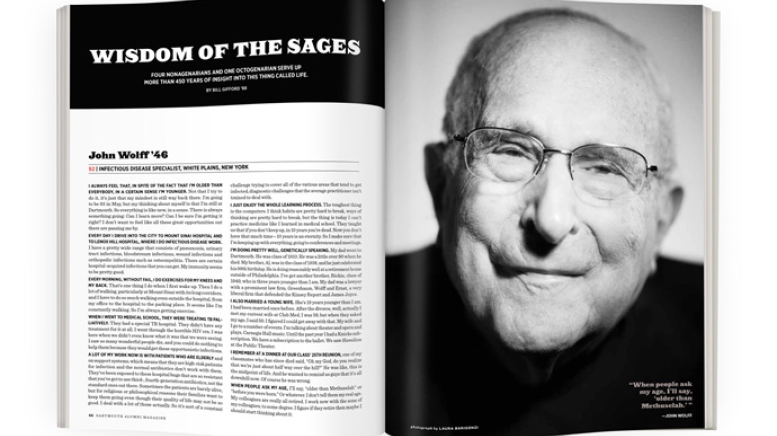

John Wolff ’46 | 92 | Infectious Disease Specialist, White Plains, New York

I always feel that, in spite of the fact that I’m older than everybody, in a certain sense I’m younger. Not that I try to do it, it’s just that my mindset is still way back there. I’m going to be 93 in May, but my thinking about myself is that I’m still at Dartmouth. So everything is like new, in a sense. There is always something going: Can I learn more? Can I be sure I’m getting it right? I don’t want to feel like all these great opportunities out there are passing me by.

Every day I drive into the city to Mount Sinai Hospital and to Lenox Hill Hospital, where I do infectious disease work. I have a pretty wide range that consists of pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bloodstream infections, wound infections and orthopedic infections such as osteomyelitis. There are certain hospital-acquired infections that you can get. My immunity seems to be pretty good.

Every morning, without fail, I do exercises for my knees and my back. That’s one thing I do when I first wake up. Then I do a lot of walking, particularly at Mount Sinai with its long corridors, and I have to do so much walking even outside the hospital, from my office to the hospital to the parking place. It seems like I’m constantly walking. So I’m always getting exercise.

When I went to medical school, they were treating TB palliatively. They had a special TB hospital. They didn’t have any treatment for it at all. I went through the horrible HIV era. I was here when we didn’t even know what it was that we were seeing. I saw so many wonderful people die, and you could do nothing to help them because they would get these opportunistic infections.

A lot of my work now is with patients who are elderly and on support systems, which means that they are high-risk patients for infection and the normal antibiotics don’t work with them. They’ve been exposed to these hospital bugs that are so resistant that you’ve got to use third-, fourth-generation antibiotics, not the standard ones out there. Sometimes the patients are barely alive, but for religious or philosophical reasons their families want to keep them going even though their quality of life may not be so good. I deal with a lot of those actually. So it’s sort of a constant challenge trying to cover all of the various areas that tend to get infected, diagnostic challenges that the average practitioner isn’t trained to deal with.

I just enjoy the whole learning process. The toughest thing is the computers. I think habits are pretty hard to break, ways of thinking are pretty hard to break, but the thing is today I can’t practice medicine like I learned in medical school. They taught us that if you don’t keep up, in 10 years you’re dead. Now you don’t have that much time—10 years is an eternity. So I make sure that I’m keeping up with everything, going to conferences and meetings.

I’m doing pretty well, genetically speaking. My dad went to Dartmouth. He was class of 1910. He was a little over 90 when he died. My brother, Al, was in the class of 1938, and he just celebrated his 99th birthday. He is doing reasonably well at a retirement home outside of Philadelphia. I’ve got another brother, Richie, class of 1949, who is three years younger than I am. My dad was a lawyer with a prominent law firm, Greenbaum, Wolff and Ernst, a very liberal firm that defended the Kinsey Report and James Joyce.

I also married a young wife. She’s 19 years younger than I am. I had been married once before. After the divorce, well, actually I met my current wife at Club Med. I was 59, but when they asked my age, I said 50. I figured I could get away with that. My wife and I go to a number of events. I’m talking about theater and opera and plays, Carnegie Hall music. Until the past year I had a Knicks subscription. We have a subscription to the ballet. We saw Hamilton at the Public Theater.

I remember at a dinner at our class’ 25th reunion, one of my classmates who has since died said, “Oh my God, do you realize that we’re just about half way over the hill?” He was like, this is the midpoint of life. And he wanted to remind us guys that it’s all downhill now. Of course he was wrong.

When people ask my age, I’ll say, “older than Methuselah” or “before you were born.” Or whatever. I don’t tell them my real age. My colleagues are really all retired. I work now with the sons of my colleagues, to some degree. I figure if they retire then maybe I should start thinking about it.

Nelson Bryant ’46 | 93 | Former outdoor columnist for The New York Times, Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts

I was 9 years old when we moved to martha’s vineyard, in the Depression. There were only five children my age within 15 miles of me. The brooks and ponds were all mine. I never encountered anybody. We lived in the farmhouse by the road. My son lives there now. This was my mother’s goat barn.

I shot my first duck when I was 11 down at the Mill Pond. I had an arrangement with the owner of the general store. If I was going duck hunting, and I didn’t have $2 for a box of shotgun shells, he would break a box for me and sell them to me for a nickel or a dime apiece. Then I’d go down to the brook and get a duck. I cook it bloody rare.

I’m still recovering from my latest fall. I was on the cellar stairs and fell down and landed on my head on the concrete. My memory has gone to hell.

I was accepted for a summer semester at dartmouth in 1942. Then I said, “Christ almighty, the world is in turmoil and I am doing nothing.” There was a program for naval officers there, but I couldn’t get in it because I have been legally blind in one eye since birth. I decided Airborne was for me.

They were doing the eye exams in a tent. I just went in and they said, “Cover your right eye.” So I covered my right eye. I have perfect vision in the left eye. Then they said, “Cover your left eye,” and here is what I did: I took my other hand and put it over the same eye. And I was in the Airborne.

We jumped into Normandy the night before D-Day. In the moonlight I see I’m coming down on a barn roof. I said, “Jesus Christ, the chute is going to collapse, and I am going to fall 40 feet to the ground.” I grabbed the shroud line. Now I’m looking at a large apple tree. I crossed my legs to save my balls and I hit the tree, and it just went crack, crack, crack and I landed standing up.

My job was to gather the company together. The invasion was behind us. We wouldn’t see them for days. Three afternoons later we went out in broad daylight, just three of us, to a French farmhouse. Out came this beautiful girl. Oh God, she was lovely. The family brought out a huge table into the yard with cognac and wine. The three of us got absolutely soused. Then she said, “These parachutes that are everywhere on the ground, do you need them? They would make nice petticoats and skirts.”

After the war I decided I’d go back to college. They had the G.I. Bill, everything paid for.

In college, poetry was my thing. There were two of us who wanted to be poets, me and Philip Booth ’47 [now deceased]. One time Dylan Thomas came to campus, and it was our job to show him around and keep him sober. We failed at that. His lecture was in Baker Library and I thought it was going to be a disaster. There were about 1,000 people there. He went up to the lectern with huge piles of paper and he shuffled through the piles and said, “Oh God.” Then he pushed all the piles away and talked straight for an hour and a half—and it was brilliant.

After Dartmouth I moved to Claremont, New Hampshire, where I got a job as a reporter. At 32 I became managing editor of the Daily Eagle. But then the publisher sold the paper and it wasn’t as interesting. I moved to the Vineyard to work as a dock builder.

At the same time I decided to write a classic war poem, and I was busting my ass. When it was almost done and I was really excited about it, the editor of Poetry magazine agreed to devote most of an issue to it. But then at the last minute they called it off. When Poetry magazine said no, I said, “F*** it,” and threw it all away. I have regretted it ever since.

I got a call from an editor at the Times about then. Their outdoor columnist had just died, and I had applied for the job. I took the train to Grand Central and decided I’d walk. The noise and the stench and the confusion—I remember saying, “This is hell,” but I kept walking. I didn’t want cities. I didn’t want crowds. I just wanted to poke around in the silence of the woods. It was all that ever made me happy and content.

One of the things that screwed up my marriage was that I was away from home six months of every year. I have regrets for the way I dealt with Jean. I could have been a warmer, more decent, less egocentric person. My girlfriend, Ruth, is a stunning woodcut artist. She just had a show at the library here in West Tisbury.

Working is the sustaining thing, not just monetarily. I still fish occasionally. I don’t hunt. I have an air gun that I use for rabbits and squirrels, but I feel bad about killing things now. As you get older and older and older, you at some point begin to fret a bit about that undiscovered country from whose bounds no traveler returns, and you say, “Jesus, this is going to happen to me.” Geese and ducks and deer lack that god-like capability to look before and after. Life becomes more precious, I think, because you know that what is left of it is very limited for you.

John Jenkins ’43 | 95 | Retired VP, Imperial Knife Corp., Hanover

The best part about being 95 is that you’re not 96.

When I met my future wife, Mary Mecklin, her father was a professor at Dartmouth. She lived here in Hanover and I would see her walking along into town, past my fraternity house.

One of my outstanding memories is of being at the Mecklin household for dinner, before we were married. Her mother asked, “John, would you mind mixing cocktails?” And I said, “Oh, thank you, Mrs. Mecklin. I’d be delighted.” I got out a glass cocktail shaker, poured the ingredients in, and was shaking it in the living room. The damn cocktail shaker broke. The ice went through and broke up all over the carpet. What do you do for an encore? I thought, “Well, I’m done.”

Another time, at the Mecklin dinner table, Mary’s father said, “John, I regret I never had you as a student.” I thought to myself, “Maybe it’s just as well.”

As a fraternity brother, I was branded. It’s a Zeta Psi symbol. I haven’t looked at it in years. I haven’t even thought about it. It’s very faint, now. It used to be very prominent. The guy who did that was a med student, and he turned out to be a very well-known surgeon in Philadelphia. He was my tennis partner.

College was interrupted by the War, where we were going to save the world for democracy. Obviously we did a lousy job. I was in the Air Force, and I was going to go to Europe, but the war ended there. Then I was going to go to the Pacific theater, and the war ended there. So maybe I was the secret weapon for us.

When I got back into civilian life, I interviewed for a job in New York but accepted another offer. When I got home, the phone rang and I picked it up. “This is Charlie Merrill of Merrill Lynch. Did you get a letter from us, rejecting your application?” And I said, “Yes, I did.” He said, “I’m calling to tell you that my secretary made a mistake—we want you to join the executive training course for Merrill Lynch.” And I said, “Jeez, I just accepted another job, an hour ago.” “Well,” he said, “I’ll give you 48 hours, and if you decide you would like to join us, please call me. Otherwise, we’ll scratch you.” And I never called him.

If I had called this guy—well, you know what’s happened to the market since those days. It would’ve been a helluva lot more money, obviously. Then I have to say, “Well, okay, did I enjoy what I’ve been doing?” And the answer is yes. That’s one of the things that I’ve always reflected on.

What am I most proud of? My family, no contest. I’m sure most parents say that their kids are marvelous, but it happens to be true in our case.

I’ve never regretted any of the time or money we spent on traveling. The greatest education in the world, to me, is travel. To find out how other people live, what they think—there’s no substitute for travel.

The only traveling we do now is to go to Nantucket in the summer. We rent a house down there for two weeks and we get together with our children and any grandchildren or great-grandchildren that can come.

One of the places that I liked best is Italy. We’ve been all over, but I like the Italians a lot. They’re a little messed up, but who isn’t?

We live in Kendal at Hanover. It’s not a place for the old folks to sit in rocking chairs. The cliché is, “You come to live, not to die.” There’s a big social life, and we’re fortunate to have a lot of good friends. I’m responsible for all the movies. It takes a lot of time and effort, and then people say, “What did you play that movie for, John? That was a dud.”

I’m the class secretary, and I keep busy doing all the obits. The class of 1943 keeps moving closer to the front of the Class Notes section of the alumni magazine. That’s a little depressing.

The longest term we think of is, “Can we get into Nantucket again next year?” We don’t go beyond that.

What advice would I give to a young person going out in the world? Be honest. Be moral. Be upright. Be interested. Get yourself a good education, keep your head screwed on straight and don’t be like this jackass Trump. If you give of yourself, you get a great return. Those are the basic values.

I want to be remembered as a good father and as a good husband. I’d like to be remembered as a friend—and that

encompasses a lot.

I’ve done a couple of smart things in my life and a couple of pretty stupid things. But the smartest thing I ever did was to talk Mary into marrying me—that I have never regretted.

After 71 years of marriage, four children, eight grandchildren and three great-grandchildren, what’s kept us together? Abiding love. One of the most powerful words in the English language is love. It’s the glue that holds everything together.

—Interview by James Napoli

Dwight Smith ’47 | 92 | Founder, North Conway Scenic Railroad, Intervale, New Hampshire

I’m 92, and all I can tell you is I feel very fortunate. Sometimes it’s a little embarrassing. My eldest son, who’s now 65, and I were traveling together, and we went into a motel. At the counter the clerk said, “Oh, are you two brothers?” I loved it.

When I was a kid I would spend summers in Groton, Vermont, and from our screened-in porch I could look across a meadow and see the tracks of a little railroad that ran between Montpelier, Vermont, and Woodsville, New Hampshire. Thirty-five miles. It was called the Wells River Railroad, and it ran four times a day, twice down, twice back. My favorite thing was to go to the station there with my buddies and watch them put water in the tank and so forth. That’s where the [train] bug bit.

I don’t play ball, I don’t climb mountains, I don’t ski, I don’t play golf.

Winters we lived in Brooklyn, New York, because my father was a merchant seaman, a sea captain, and his home port was Brooklyn. I didn’t really have a father growing up. Basically my memories of my father are not the fondest. I was brought up by three women: my grandmother, my mother and my sister, who is four years older than me.

In July of 1943 I was on The South Dakota, the most battle-weary ship in the South Pacific fleet. I was only on it for nine months, and I have four battle stars on my Pacific ribbon. At one point [the officers] asked if anybody had taken high school math. I raised my hand and got a job in the plotting room in the bowels of the ship. I’d have headphones on and I was getting data from up top and we had a computer full of vacuum tubes in the plotting room, hotter than hell.

The Japanese kamikazes kept trying to sink us, and every boom, I can hear it all. I’m in danger, I guess, and not too happy about it.

We had 2,400 crew members. It was posted on our bulletin board that The South Dakota had been given a quota of five crew members who could be sent back to the V-12 College Training Program. Once again, I raised my hand. When you volunteer, sometimes it’s worthwhile.

So I became a college boy. I have this picture of the Green with white-uniformed sailors all lined up, marching, and I’m the only one with a ribbon that had four stars on it, so I’m carrying the flag. I was the only veteran in the unit.

Then I met [my future wife] Gertrude, who had a summer job outside of Windsor, Vermont. I was in college all summer with my car, so every evening I’m puttering up to where she was working. Things went well. We were married for 62 years, I called her “Gee” and I was “Bud.” We just enjoyed each other’s company. [Gertrude died in 2010.]

When I got out of the Navy I said to her, “I may go back to sea,” and she said, “The sea or me.” She knew what my mother went through. Three days after I graduated in February 1947 I reported to Boston & Maine Railroad in Boston. I was in their freight and traffic division as an office boy. You’ve gotta get your foot in the door.

I worked for the B&M for 26 years. Toward the end, we were spiraling down, and I was getting nervous. One weekend I took a ride on a train that ran from Boston to North Conway, New Hampshire. This was a special train, once a year. I stayed put and I looked around that railroad yard, the beautiful station from 1874, with a roundhouse, turntable, freight house, beautiful mountains and the main street. In other words, wow, what a location!

I went over across the street to some of the restaurants and stores to ask questions and they told me these two gentlemen owned the station. They had no commercial design to use it. So I said, “Well, maybe there could be a commercial use.” We shook hands. No papers ever passed. We ended up with a corporation and each had one-third shares.

It took six years, but on August 4, 1974, we ran our first train on our scenic railroad and sold 94 tickets with no advertising of any sort because people heard the whistle. I came up here without a house, without any money to speak of, two kids [of five] in college and no real job. I always say I got out on a long limb and sawed it off. Time after time again, people said to me, “You’re foolish. It will never work.” I said, “I’m gonna find out.”

Carl V. Granger Jr. ’49 | 88 | Physician/professor, Buffalo, New York

I never heard of aging. I just let it sneak up on me.

I got into medicine because my father was a doctor. He was one of six boys, five of them doctors and dentists. So we had a tradition. That was all I expected to be.

My grandfather was also a doctor. He had stowed away or was working on a ship from Barbados, and he got off in Philadelphia. He was taken in by a Quaker family who sent him to college then medical school at the University of Vermont. He and his wife moved to Arkansas, then to Oklahoma. Eventually they ended up back in Newark, New Jersey, with their six boys. Five of them ended up going to Dartmouth, including my father, who was class of 1923. So we had a tradition of that, too.

I was born in Brooklyn. My father was practicing there, but then he decided it would be healthier to move out to Long Island. We moved to Huntington, and he made house calls, hospital calls, private office visits. We had a garden and apple trees.

There was one other African American student in my high school. At Dartmouth there was one or maybe two. I’m used to being a minority. I just took it in stride.

After I got out of medical school and did my hospital internship, I started practice in my father’s office. Then I got drafted into the Army and they said, “What do you want to do?” I said, “What is available?” They said physical medicine, or radiology or something like that. And I said I think I’d like physical medicine.

Physical medicine was a relatively new specialty after the war. It dealt with people who had difficulties in their functioning, from their war injuries or from illnesses. A lot of my patients had had strokes, and it was a matter of rehabilitating them so they were better able to function. That was an attractive idea to me, helping people to recover and, over time, watching them recover and improve and build lives that were possible. It was not just myself, either: The team consisted of physical therapists, psychologists and nurses. It was satisfying teamwork that wasn’t available in other types of medicine.

Then we realized we had fixed them, but we didn’t have any record of how much we had done. We had to measure it. And when the patient was discharged from hospital it was essential to get some idea of how much they were going to need help and what arrangements need to be made to provide it.

They would tell me I couldn’t measure it, that I was measuring the impossible. But we figured out a way. We developed something called the FIM instrument—Functional Independence Measure. It’s a scoring system that measures the degrees to which a person is able to be independent. It looks at activities of daily living. Some of it is intellectual, the ability to keep track of things. Speech is also taken into account as is their ability to walk or run or use a wheelchair. The whole score is added together and sort of gives a summarization of how that person is doing.

It’s a measurement that’s used worldwide now to demonstrate the outcomes of rehabilitation. It’s also a basis for planning how much the insurance company is going to pay the hospital. Medicare uses it. I’m the director of uniform data systems for medical rehabilitation at the University at Buffalo, where we manage a database of more than 13 million patient assessments now. We do benchmarking, comparing one facility against others in a region. To be accredited a facility has to prove it provides quality care and that they are tracking their outcomes.

I’m lucky—I’ve had no major surgeries or illness. One thing that has been stressful is having my wives die: You’re in love and getting along fine and then they’re not there anymore. My second wife, Joanne, I’d known since we were kids. We were family friends. She died 20 years ago. My third wife, Eloise, died about two years ago. I have a lady friend now who I spend time with. My advice is to look for someone who’s a friend. You can’t carve a person out to be the person you design—you have to take them for who they are and make the most of it. If you don’t accept them for who they are, forget about it.

Living longer is not necessarily a blessing if you don’t have a good quality of life. I love going to work, although I’m out of patient practice now. Retiring is appealing, but I haven’t done it. I officially “retired” at age 75, but I never actually did. I had a retirement party, but I never left.

Bill Gifford is the author of Spring Chicken: Stay Young Forever (Or Die Trying).