End of an Era?

From a distance it can be hard to distinguish death throes from the twitchings of new life. And the murky area of life support always raises hard questions, be it an elderly relative—or an aging tradition at the heart of a 250-year-old institution.

In early January 2016, looking out at bare ground, students on the Winter Carnival Council conceded there would be no center-of-the-Green sculpture that year to mark the College’s famous celebration of winter. Since the first Carnival in 1911, any number of special traditions had melted away with the changing fashion of the times: skijoring (races were so popular that results were reported in The New York Times), ice dancing (which featured Olympic-caliber figure skaters), the Winter Ball, the crowning of the Carnival Queen, the spectacle of the 50-meter ski jump on the golf course with thousands of cheering spectators, the keg jump at Psi U, which attracted hundreds.

Since the 1920s, though, outside of the war years there had never been a Carnival without a sculpture.

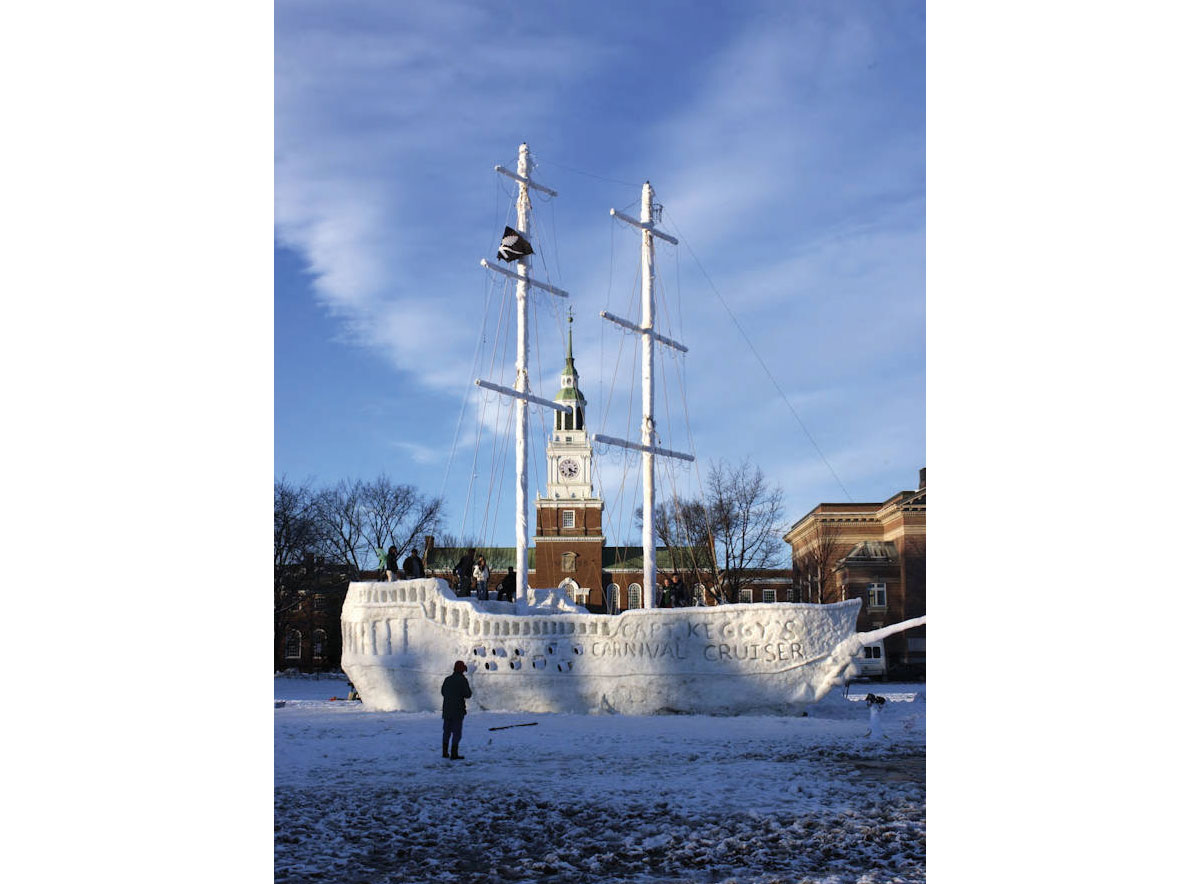

Many years, the creations were spectacular. In 1939 a caricatured Eleazar Wheelock raised a tankard skyward. In 1956 Ullr, the Norse god of skiing, towered 45 feet above the Green. An enormous dragon in 1969 breathed real fire from a butane torch. A rotund, vaguely Mrs. Butterworth-like saxophone player set a Guinness record in 1987 as the world’s tallest-ever snowman. In 2005 students constructed an elaborate, twin-masted pirate ship some 18 feet wide and 56 feet tall, with working cannons and an 8-foot slide above deck.

Many of the sculptures were statuesque works of art that seemed to defy physics and the properties of frozen snow. They were featured in movie reels and television specials, in publications ranging from National Geographic to USA Today. A 1960 article in New Hampshire Profiles reported that the sculptures at Dartmouth required 2,000 man-hours of labor, “equal to a year’s work for one man with a two-week vacation thrown in.”

All of which created a public face for Dartmouth’s historic embrace of winter that added to the reputation of the College as the home of go-for-it, hard-working, tradition-loving, slightly crazy students.

~ Click here to view a gallery of Winter Carnival snow sculptures through the ages. ~

The 2016 decision, alas, followed a string of underwhelming efforts and waning student enthusiasm. “The main factor was obviously weather,” council chair Harrison Perkins ’18 told a reporter for The Dartmouth. “There’s not really any snow. The second factor was a lack of student support in building the actual sculpture in the past few years.” The paper quoted two frustrated former sculpture chairs. Ben Nelson ’17 had struggled to enlist volunteers the previous year. “The sculpture is not important enough for students,” he said. “Everyone loves seeing it. People love taking pictures of it. People don’t really seem to love building it.” He did much of the work alone.

Benjamin Meigs ’10, Th’11, an engineering major who had taken the lead on three sculptures and been graduate advisor on a fourth, had a similarly lonely experience. He told The Dartmouth, “Students just didn’t want to make a commitment to help. [They have] gotten more about preprofessional prep and less about finding unique experiences. Building something out of snow in the middle of campus won’t stick well on your résumé.”

Years later, he says, “When you care about something, you do the work. I took on rallying students as kind of a personal crusade. We passed the torch to a few folks. But three, four years later the torch fizzled and then got dropped.”

Predictably, The Dartmouth Review published a lament for the passing tradition, calling that 2016 winter “Dartmouth’s Days of Skulpturkampf.” On Dartblog, Joe Asch ’79 posted a piece titled “Snow Sculpture RIP?” Both decried the sad state of apathy among a changing student body. Both suggested that something fundamental was shifting in Dartmouth’s foundation.

“I hear alumni grumbling about ‘students these days,’ ” says Rory Gawler ’05, assistant director in the outdoor programs office. “Mostly by alums who probably didn’t put in the work themselves back in their day. They say, ‘Students now are too busy.’ They complain about so many students coming to Dartmouth without even knowing about winter.” (For a long time, California alone has sent more students to Dartmouth than New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont combined.) “But I can tell you that involvement in winter trips in the DOC is way up. And I’ve seen students get excited and put in a ton of work on the sculpture, only to have warm temperatures or rain come in and ruin it right before Carnival. You get that gut-punch more than once, and you can understand why students might lose fire.”

In January 2017, a month of above-freezing days, the council announced that no Carnival funds would be used for a snow sculpture. Instead, the money would be allocated to other weekend activities, including a Hogwarts-themed opening night reception in Collis Center, complete with “golden snitch pops,” “butter beer,” and live owls.

The DOC alumni listserv lit up with complaints.

At the last minute a few intrepid students reached out to local alumni and residents, who scraped together funding and trucked ice shavings to the Green from nearby Campion ice rink. A few students turned out and hastily sculpted a crude, low-to-the-ground, serpentine dragon. You could easily look beyond it to Baker Tower—and hear the clock ticking.

One of those locals, Bill Young, a Hanover resident who had informally pitched in on 20 years’ worth of sculptures, wasn’t willing to let the tradition go. As director of the town’s popular parallel winter celebration, the Occom Pond Party, he knew how to organize and had cultivated contacts around the procurement of snow and the carving of ice. He strategized with local alums, including Peter Frederick ’65 of the Sphinx senior society’s philanthropic alumni group, the Sphinx Foundation. Frederick looked into the funding issue.

As David Pack, associate director of student involvement, later explained, bringing in snow for the sculpture had been taking an increasingly large bite out of the Carnival budget. “We were spending it on a piece of the weekend that wasn’t seeing the most student engagement,” he says. The polar bear swim was hugely popular. The ice-carving competition, an event added in 2014, had a waiting list. The outdoor opening ceremony and official “unveiling” of the snow sculpture had become a brief, poorly attended event. “The sculpture, we realized, resulted from a great deal of effort by a small part of the student body,” he says. “The decision to spend money elsewhere was made by the students on the Carnival committee.”

Frederick was surprised by the $3,500 sculpture budget—it seemed small to him. The Sphinx Foundation—dedicated in part to preserving College traditions—promised to fund that amount for the 2018 effort. Young signed on as an advisor, and the historically student-led, College-funded snow sculpture was officially on life support.

Pack took a wait-and-see approach to future funding. It wasn’t really about the money, he says. “If we wanted to hire a professional carver to create a stunning sculpture for the community, we could do that,” he says. “But is that what we want to do? Former Carnival chairs don’t talk about the sculptures they created. They remember the friendships and the whole process of planning and building. That’s what’s meaningful.” The College would support the tradition, he says—but first, the students would need to step up.

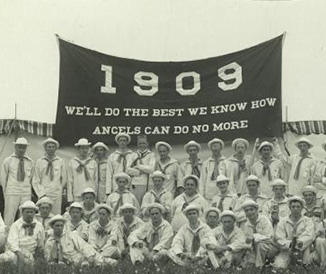

Snowmen on the lawns in front of dorms and fraternities had been a feature of Carnival from its earliest days. By 1929 snow sculpting had become a formal, campus-wide competition. Responsibility for overseeing the main sculpture fell, along with the other activities, to a Winter Carnival division within the Dartmouth Outing Club. Pennington Haile, class of 1924, designed the first all-campus sculpture, a castle. Students built it with blocks of ice purchased from the Hanover Ice Co. Within a decade the Green’s centerpiece had become a sophisticated marvel of engineering, utilizing wood or steel armatures (one year, a 30-foot telephone pole), wire mesh, fabric coverings, multistory scaffolding, ladders, platforms, pulleys, cables, hoses, and, for nighttime work, floodlights. Snow wasn’t so much packed hard and carved as it was turned into freezing slush and plastered onto infrastructure.

Besides the Thayer School engineers and the College maintenance crew, the bulk of the work in those early years fell as a rallying cry to the freshman class. Through the 1940s and 1950s, as out-of-town visitors swelled Carnival crowds to 6,000 and more, the task of organizing Carnival events weighed increasingly on the chubbers in the DOC. Members complained about the workload, but the club held onto the responsibility until Dartmouth voted to move to the trimester system and the challenge of the new winter schedule became too much. The DOC moved to dissolve its Carnival division in 1961, citing the “inconsistency of these events with the club’s purpose and the health and academic standing of its personnel.”

Through the decades since, student complaints about the burden of planning and building the sculpture became an annual refrain. Even the students in 1969—responsible for the elaborate, fire-breathing dragon—felt compelled to write a letter to the administration pleading for help from staff and faculty. Beer could no longer be offered as an incentive. Varsity teams and fraternities sometimes pitched in on shifts to help, but more years than not, a hardy, dedicated few carried the bulk of the work. In 1971, citing declining student interest, the Newark Sunday News ran a headline: “Carnival on Downhill Run at Dartmouth.”

And no one could ignore the changing weather.

Dating back to 1925, unseasonably warm or dry or wet winters had been an occasional feature of the Carnival. Glossed over in the wintry College narrative, scant snow cover caught in the background of old sculpture photos attests to a number of low-snow years. During the past quarter-century, rarely has a sculpture been built solely from natural snow—in the past 15 Carnivals, without enough white stuff to ski on, Dartmouth has had to relocate its Nordic skiing races to northern Vermont 11 times.

Students have improvised, sometimes creatively. When the knight battling a medieval dragon fell due to warm weather in 1997, students scrambled to refashion the sculpture into a funeral scene, complete with coffins and snowmen mourners. In 2009, the centennial of the DOC, the southwest wall of an elaborately designed Moosilauke Ravine Lodge sculpture softened and collapsed. Worried about student safety, the College bulldozed the sculpture and its wooden supporting structure-within-a-structure. Dozens of students—and President Jim Wright—answered a frantic last-minute call and worked through a night of freezing rain to turn the snow pile into a semblance of Mount Moosilauke’s familiar twin-peaked profile. “Having President Wright out there meant a lot to me,” says Meigs, who had worked heroically through the disappointment. “He wasn’t there just for a photo op.”

After the collapse, the College’s risk managers introduced restrictions on the use of internal structures in the design. Sculptures would now need to be carved from solid blocks of snow and ice. The restriction, which made sense from a safety perspective, compounded the hurdles facing the Carnival Council. With increasingly unreliable snowfall and labor, sculptures would require more snow and more labor. Designs would need to be submitted for permitting and approval long ahead of time and necessarily become smaller and less complex. As a result they would also be less exciting, less inspiring to potential workers and future leaders of the effort.

Then there was the calendar. The quarter system known as the D-Plan had long since created a continuity and logistics challenge for Carnival planners. When Dartmouth instituted a long break between Thanksgiving and the New Year starting in fall 2012, crucial preparation time was lost. Students now returned to campus in early January after six weeks off, with no rising sense of anticipation, no cabin fever to release, and only 24 or 25 days to build a sculpture while preparing for midterms. And while facing February 1 deadlines to apply for off-campus programs and summer internships.

The sculpture tradition neared a melting point.

Just before Thanksgiving in 2017, Curt Oberg ’78 and his wife, Sherri (Carroll) ’82, Tu’86, invited some football players to dinner at their home just south of downtown Hanover. Curt, an assistant football coach, had made the informal gatherings a habit. This one had a special agenda: the uncertain fate of the snow sculpture. Curt had been a sculpture chair as an undergrad, responsible for the magnificent juggling clown at the center of “The Greatest Snow on Earth.” He recalls the unexpected bonding and friendships he’d made with students from across campus that winter, not to mention the joy of the work. “It was a different time,” he says. “I’d be at the top of an iced-over, 30-foot-high set of scaffolding, not roped in, swinging an ax in my hand, chopping away.” Sherri, a former Dartmouth trustee, also had fond memories of Winter Carnival. They were both connected enough to the College to know the sculpture tradition was in trouble and wondered how they could help.

They invited Young and Frederick to the table, along with Martha Beattie ’76, then VP of alumni relations. They got to talking with one of the football players, Andrew Yohe ’18, Th’19, an engineering sciences major who was interested in building structures. The Obergs were renting a room in their house to Zoe (Dinneen) Thorsland ’18, a chainsaw-certified rower and studio art major who had won the previous year’s ice-sculpting competition. “We had these two complementary skill sets right there in the house,” recalls Sherri. “All we had to do was put them together.” A wide-ranging conversation turned into a strategic planning session. Yohe agreed to get his teammates to commit time to the sculpture project. Thorsland would design the sculpture and rally the rowers. The students mapped out logistics, a schedule, and a succession plan to pass on what they learned.

Thorsland got a copy of the manual that Meigs had put together with former sculpture chair Dan Schneider ’07. “You mean you’re shoveling snow into buckets and walking across the Green?” she asked. “We don’t have time for that.” She connected with the Skiway and had six truckloads of machine-made snow dumped on the Green. Frederick and Young arranged for a Vermont contractor to donate wooden forms that were normally used for pouring concrete. A bucket loader operated by Dartmouth’s facilities crew filled the forms with snow and football players stomped it down. The Obergs hosted more meetings. Young had ice cut and delivered from Occom Pond for the translucent front of the sculpture—Darth Vader’s helmet—through which LED lights would shine. The Sphinx Foundation picked up the bill for everything.

The resulting sculpture “was a start,” says Thorsland, though other observers were less charitable. In size and detail, the Vader helmet was a shell of sculptures past. And the student turnout for the effort, beyond football players and female rowers, was anemic. The magnetic holiday atmosphere—the heady, carried-away feeling the project once inspired—seemed a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away.

Was this an example of the adults and professionals taking over a student tradition? Sherri Oberg prefers to think of their role as a bridge. “We were there to support the students, not do the work for them,” she says. “And what we saw was amazing: students learning leadership skills, team-building, planning, communication. It was experiential learning at its best.”

Thorsland says she loved working side by side with the broader community. “If this tradition is going to continue,” she says, “students need to realize it’s not the same as it was. It used to be about bonding and fun. Now it’s about, ‘How can we get this done?’ ”

At a debrief meeting in the spring of 2018, an energetic freshman from Dallas, Chris Cartwright ’21, showed up and grabbed the sputtering torch. He’d worked trail crew with the DOC and felt strongly about keeping Dartmouth traditions alive. He welcomed the alumni support, met with the Obergs, kept the momentum going the next winter through 50-degree weather and discouraging rain and sporadic student turnout and pulled off a not-so-mammoth woolly mammoth on a toboggan sliding toward a “250,” marking the school’s 250th anniversary. “It wasn’t the greatest sculpture,” Cartwright says. “But I went from never having done anything like this to being completely in charge. I learned so much about what we could do differently next time.”

The College, sensing a reemergence of student energy and recognizing the benefit of alumni involvement, had agreed to a new sculpture funding model. Three sources would contribute equally: the alumni relations office, the office of student involvement, and the Sphinx Foundation. Alumni relations staffer Briana Gochenour arranged an alumni volunteer day, and folks showed up from classes in every decade going back to the 1950s—a big success from her office’s point of view. “We’ll make this as sustainable as we can,” she says. “No matter what we do, 40 degrees won’t work. But we can do a lot with 35.”

Cartwright signed up to lead the charge again in 2020, aware of the shifting culture on campus, the career pressure felt by students, the indoor pull of Netflix and the internet,

the seriousness that made slightly crazy traditions seem increasingly frivolous. “The world has changed,” he says. “And you can see how the world has changed through things at Dartmouth. The bonfire used to be totally student-led. With insurance and liability concerns, professional contractors now do most of the work of actually building the tiers. I would rather have the snow sculpture tradition fail than become that.”

In the fall Cartwright lobbied to formally move the oversight of the sculpture back within the DOC, to take advantage of the club’s tools and logistical experience and to create continuity year-round. Gawler agreed to give the sculpture committee a home in Robinson Hall—not as a new club within the DOC, but as a special project, like the annual 50-mile Moosilauke hike. He promised to move any obstacles he could, but made it clear that the work was up to the students. “Alumni can’t prop this up,” he says. “You can’t put a crutch underneath the sculpture and expect students to make it work. Student affairs professionals need to let the tradition fail, if it’s going to fail, so students will have to want to resurrect it.”

The question of life support will be answered in time.

Dartmouth being Dartmouth, Winter Carnival will likely survive warmer winters even if that means indoor climbing-wall competitions instead of Nordic skiing—or Thayer students creating a dome with cold air blasted in to sustain the ice-sculpture contest. In the meantime, alumni and locals partnering with students to defray the labor and cost of constructing something monumental on the Green might be a reasonable compromise.

“I actually like the alumni involvement,” Cartwright says. “But it needs to be driven by students. We have DOC members who are van-certified. Maybe we could get some to be loader-certified.”

He was planning to devote his winter off-term to the task. Along with Frank Sapienza ’21 and Luca Di Leo ’22, he sketched out a serpent design to highlight the Carnival’s theme: “A Blizzard of Unbelievable Beasts.” Its 28-foot height reflected Cartwright’s belief that bigger is better, that a large sculpture could be impressive, even inspiring, without the fine details needed to carry a small one—details that were vulnerable to both melting and being covered by new snow. The wedding cake design of the serpent’s long neck and head was simple, easy to carve, with natural structural support, and could be reduced to as little as 12 or 14 feet if snow or volunteers didn’t materialize as hoped for.

He scheduled deliveries of artificial snow from the Skiway long in advance, as a precaution. In the second week of January, Cartwright hired a facilities bucket loader to pile up the sculpture’s first eight feet of height. He also sent out forms to every group he knew, targeting friends who were involved with sports teams and Greek houses. He sent a signup form to every undergraduate advisor, students who oversee floors of first-year students in the dorms. With DOC members, he created a challenge to dump the most buckets of snow between the sub-clubs. He asked WDCR DJs to rock some music on the

Green, ordered pizza and hot chocolate, and tried to get the fire back in students who had been gut-punched by the weather and turn the burden back into a party.

A few weeks later, most forms remained blank. Students withdrew their promises to help and recruit. Many were too busy with academics and other activities. Fraternity brothers told him they weren’t interested in manual labor in the cold. Cartwright held a campus-wide interest meeting on January 9 and gave leadership positions to ’22s and ’23s to keep the line moving. Next year he could serve as a mentor and advisor. Add to the manual. Pass down the torch. “A lot is riding on this year, I guess,” says Cartwright.

Two days later the temperature in Hanover reached 58 degrees.

Jim Collins is a DAM contributing editor.