The Professor Was a Spy!

The blue-eyed Dartmouth professor met the raven-haired British beauty at a wild party on his first night in war-weary London in February 1943. Wentworth Eldredge was a recently commissioned captain in the Army Air Corps. Wasting no time that night, he and two fellow officers crashed a posh wedding party at a private club. They were soon speeding toward a West End nightspot in a cab with several young women—including 23-year-old Diana Le Poer Trench. “Six of us decided to go to the 400 Club and Diana got huffy a bit about sitting on my lap,” remembered Eldredge. “Those marvelous London cabs were built for a limit of five.” The wee hours saw the two of them stepping out to the strains of an 18-piece orchestra on a dimly lit dance floor.

Eldredge had no way of knowing how this chance meeting would change his life—and, in its own way, affect the course of World War II. Le Poer Trench’s stepfather was a bestselling novelist with a shadowy job in British intelligence. Father and daughter drew the professor-turned-military-man into a dark-arts world of cloak and dagger—a secret war of deception against the Nazis. Eldredge helped implement one legendary military deception and was instrumental in directing another, all the time wooing Le Poer Trench, who had her own secrets. “He loved the adventure, he loved the secrecy,” says their son, Jamie Eldredge ’73.

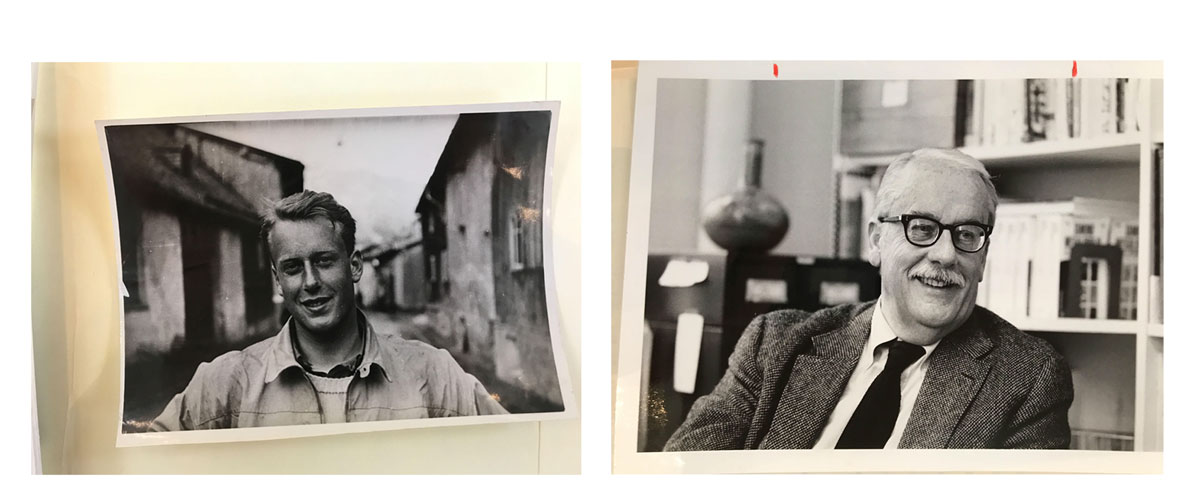

From the late 1930s to the mid 1970s, except for the war years, “Went” Eldredge was the epitome of an establishment professor. A Brooklyn-born Dartmouth grad with a Ph.D. from Yale, he chaired Dartmouth’s sociology department and ran programs in city planning and urban studies as well as international relations. He consulted with various government agencies and lectured at NATO. He was also a founding trustee of Outward Bound in the United States. At cocktail parties he was not shy about sharing amusing stories from his wartime years, but he was guarded about the specifics. It wasn’t until the last few decades—after documents were declassified, tongues loosened, and Eldredge’s unpublished memoir and private correspondence surfaced—that the whole story came to light.

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, the young assistant professor took a leave of absence from Dartmouth to offer his services to his country. He worked for the war division of the U.S. Department of Justice, was briefly attached to the U.S. State Department, then joined the Army Air Corps, where he was commissioned as an officer and trained in military intelligence.

Upon arriving in London, though, he was given only mundane writing and research work that had nothing to do with intelligence. “I was getting increasingly bored with being assistant historian of the 8th Air Force—not what I signed up for!” he wrote in his memoir. Eldredge compensated with a swinging nightlife and spent time with an assortment of partners. But when he was hospitalized with jaundice in Oxford, he found out who really cared about him. “I worked up enough energy to want to see some of the ‘lovelies’ from London town. Diana was the only one who nibbled to come up over a weekend.”

Le Poer Trench was a child of the British upper class, fluent in French, German, and Italian. Before the war she had been a painter. A direct descendant of King Henry VII of England, Le Poer Trench also happened to be married to the son of an earl who was off serving in a distant outpost. She and Eldredge fell hard for each other. In wartime London, peacetime morality became the first casualty.

Le Poer Trench’s stepfather was Royal Air Force Wing Cmdr. Dennis Wheatley, a prolific and popular British author of detective and spy novels. “He had a vivid imagination and was a very colorful character indeed,” remembered Eldredge. “His blue (RAF) officer’s coat was lined with scarlet silk and he carried a leather swagger-stick (a concealed sword cane)—both non-regulation.”

A lover of sumptuous meals and a heaping helping of intrigue, Wheatley was apparently on speaking terms with everyone in the British government. Eldredge became dimly aware that Wheatley had a hush-hush, high-level job but did not know the whole truth: Wheatley was entrenched in the ultra-secret London Controlling Section, military deception strategists for the British joint chiefs of staff.

In late 1943, six months before D-Day, Wheatley wanted to make sure that American officers chosen to coordinate with British deception efforts would be smart enough to master the challenge and trustworthy enough to keep some of the British government’s most important secrets. “Dennis was devoted to his beauteous stepdaughter, Diana,” wrote Eldredge. “He asked her did she know some bright American who did not have ‘a big mouth’ (a national failing). Diana answered she knew one…who might fit the bill.” Eldredge found himself invited to Christmas festivities at Wheatley’s flat, where he was awed by the generals and air marshals who kept dropping in. It gradually dawned on him: He was being vetted by the British military.

Through Wheatley’s influence, Eldredge lunched with Maj. Ralph Ingersoll, an American who made a powerful impression. “I never met such a bright guy who was such a goddamn liar,” Eldredge recalled to Ingersoll’s biographer. A flamboyant celebrity journalist and author in civilian life, Ingersoll had a genius for trickery. “Any problem, he would just think a bit and come out with something,” mused an admiring Eldredge. “This was damn irritating for a college professor. He was always three moves ahead of you.”

Ingersoll arranged for Eldredge to join the American planners. The newly minted deceiver visited what he called “the holy of holies,” London Controlling Station’s underground nerve center in a top-secret fortified bunker, steps from Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s cabinet war rooms. From this heavily guarded rabbit warren of narrow, dimly lit corridors and tiny offices, the British government ran its war effort—and Eldredge’s British counterparts initiated him into the clandestine world.

The British had embarked on one of the most audacious pieces of military trickery in history. Their goal: convince the enemy that a massive Allied army under Gen. George Patton was gathering in southeast England, preparing to invade France at Pas-de-Calais. It was a sleight-of-hand. The real Allied invasion would land 150 miles down the French coast in Normandy.

Eldredge, Ingersoll, and their boss, Col. Billy Harris, coordinated all the American aspects of what became known as Operation Fortitude, a strategic ruse that played a critical role in the success of the D-Day landings.

British spymasters had turned every German agent in England and used them to feed misinformation to the Nazis. The most effective of these double agents was Juan Pujol García, known as “Garbo.” One of Eldredge’s jobs was to come up with what he called “juicy things and true-sounding things” about the fake American army and supply Garbo and his fake spy network with plausible fictions. “It was an incredible operation,” Eldredge later wrote, “juggling the reporting of about two dozen imaginary sub-agents who did not exist.”

The lies would be meaningless unless the Germans believed them. He harbored doubts about whether this “chicken-feed,” as he called it, was serving any purpose and demanded proof that German commanders believed the deceits. He met with U.S. Army Col. Telford Taylor, later a famed prosecutor at Nuremberg. “I went to see Taylor, who said pleasantly enough, ‘Hello, Eldredge,’ then stopped and started again when all the curtains in the room were drawn. His manner changed, and he said very seriously that I would be shot if I revealed what he was going to tell me. This brought me up sharply as I, of course, answered, ‘Yes, sir.’ ”

Taylor revealed one of the biggest secrets of the war: British code breakers at Bletchley Park had broken the Germans’ supposedly ironclad Enigma code. Taylor was responsible for distributing that top-secret intelligence—code name Ultra—to Americans with a need to know. Eldredge was inducted into that select group so he could gauge how the German high command was reacting to his phony stories. “I thought, ‘No more drinking,’ and I hoped I did not talk in my sleep,” he remembered. He was soon privy to a heady mix of secrets and insider access. “I felt I’d burst if the Army had one more reason to shoot me.”

After D-Day, Eldredge and Ingersoll crossed into France as deception planners for the 12th U.S. Army Group under Gen. Omar Bradley. They cooked up a multitude of battlefield deceptions utilizing a top-secret American detachment that earned the nickname “the Ghost Army.” This one-of-a-kind unit deployed inflatable tanks and artillery, broadcast sound effects from giant speakers, and used radio spoofery and dazzling impersonations to fool the Germans about the location and size of actual units. Eldredge rigged up a map room in a converted ambulance. At key points in the war, the Ghost Army secretly helped American commanders by disguising weak spots in the line or drawing German attention away from attacking forces. The details remained under wraps until the 1990s.

When Bradley moved his advance headquarters to Luxembourg City in September 1944, Eldredge and Ingersoll moved as well. Their secret war had its perks. Bradley and his staff commandeered a hotel where Ingersoll hosted evening martini parties: British gin, vermouth liberated from the Wehrmacht, and lemon powder from K-ration anti-scurvy packets. “Marlene Dietrich was there on occasion in GI fatigue clothes…while her ‘date,’ Georgie Patton, was having talks with Omar before dinner. She was always sparkling,” wrote Eldredge.

They were still in Luxembourg City in December 1944 when the Germans launched a major counterattack: the Battle of the Bulge. German planes strafed Luxembourg City—artillery could be heard in the distance. Sensitive documents had to be destroyed. Ingersoll decided to bury their papers in a fake grave, which they marked with a wooden cross and the helmet and dog tags of Kelly, their driver. “Ingersoll was in high glee,” wrote Eldredge. “Kelly did not think it so funny.”

German infiltrators in American uniforms wreaked mayhem. Tense GIs quizzed any soldier they didn’t recognize about arcane details of subjects such as baseball to suss out Nazi fakers from real Americans. Back in London, Diana Le Poer Trench grew concerned that Eldredge, hardly a sports fan, would be caught unaware. She sent him a cable over the top-secret Ultra network to make sure he knew the 1944 pennant race winners, “which she rightly knew I had no idea of,” he wrote. The information proved invaluable. “Hard-eyed GIs were on each side of the road with machine guns pointed at our jeep as a no-fooling GI asked all sorts of stiff questions only a ‘good American’ could answer. I used Diana’s info several times, but I usually swore at the goddamned characters who were holding us up.”

Meanwhile, Le Poer Trench enjoyed her own secret adventures. At the same 1943 Christmas soiree where Eldredge was scrutinized, she was approached by Brigadier Gen. Colin Gubbins, head of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a secret British force that carried out sabotage and subversion missions behind enemy lines. “Would you like to be doing something more interesting?” Gubbins quietly drawled, recruiting her on the spot. Eldredge had no clue.

“I did not learn about it until 20 years after we were married,” he later recalled, “when Diana, talking French in her sleep, started to talk about parachutage.”

Once his wife started talking, she painted Eldredge a stunning picture. She told him that she had been a courier-agent code-named “Precious Cargo” and had parachuted five times into Nazi-occupied France. She’d also been on two secret missions to Belgium by boat and been part of another operation that eliminated 89 Germans. At one point the Gestapo captured and interrogated Precious Cargo before Belgian commandos freed her. “[She was] offered the George Cross, French Croix de Guerre, and the Belgian Croix de Guerre,” wrote Eldredge in a letter two years before his death. “Churchill himself offered her the George Cross, but she refused them all and said she in no way wished to become conspicuous in America.” Their son, Jamie, remembers British officials coming to their home in the 1970s to make a secret medal presentation to his mother.

Le Poer Trench’s SOE file remained classified for more than 75 years (a request under the Freedom of Information Act by DAM opened it in 2019). It confirms her personal recruitment by Gubbins but says only that she was a secretary. More revealing documents were destroyed in a fire shortly after the war. The full extent of her wartime exploits may never be known.

The Battle of the Bulge offered Eldredge his one chance to confront the enemy. On December 31 the Germans launched a major air attack with more than 1,000 planes targeting the Americans. Well lubricated from a blowout New Year’s Eve party in the French city of Metz, Eldredge awoke to the sound of gunfire hitting his building. “Staggering to the window, .45 in hand, I fired two or three at a black shape, a Me-109 [Messerschmitt fighter plane] with a white cross on its fuselage, which barreled down the street just a little higher than my window,” he wrote. “These were the only shots fired by me in anger during the whole damn war!”

After the war Le Poer Trench secured a divorce and came to Hanover with Eldredge. They married in 1947 and bought a house on a quiet hilltop in Norwich, Vermont, where they were “happy to lie low,” in Eldredge’s words, after the excitement of their wartime years. They had two children, Jamie and Alan ’75. Eldredge continued teaching until 1974, while his wife worked as a professional artist. He died in 1991 at age 81. She died eight years later at age 79.

Few if any of his students knew that the loquacious professor and his quiet wife had operated deep inside a secret war. “It was a most curious story,” mused Eldredge years later, “to be snapped up into the center of the war effort because I knew a charming Scot-English lass, a popular writer in the United Kingdom…and then as unique and devious a character as you’d find, Ingersoll. So I landed in the ‘armpit of the tortoise’ in this strange fashion.”

Eldredge had no regrets: “It was clearly the high point of my life.”

Rick Beyer is a coauthor of The Ghost Army of World War II and a member of the DAM editorial board.