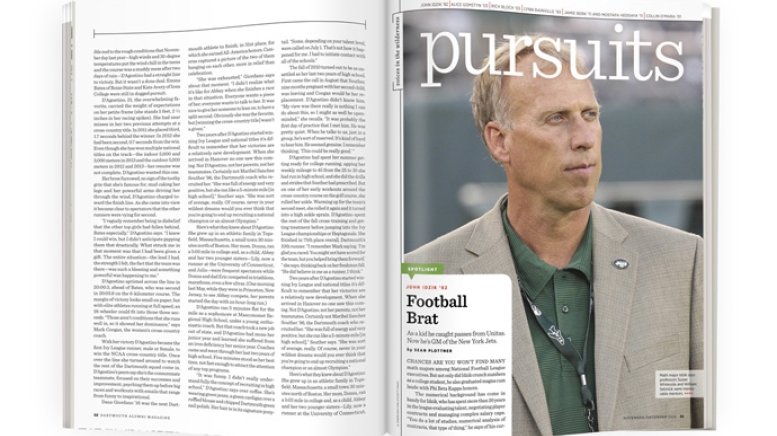

John Idzik ’82

Football Brat

As a kid he caught passes from Unitas. Now he’s GM of the New York Jets.

Chances are you won’t find many math majors among National Football League executives. But not only did Idzik crunch numbers as a college student, he also graduated magna cum laude with Phi Beta Kappa honors.

The numerical background has come in handy for Idzik, who has spent more than 20 years in the league evaluating talent, negotiating player contracts and managing complex salary caps. “You do a lot of studies, numerical analysis of contracts, that type of thing,” he says of his current role. “It’s not football in its purest sense.”

Idzik’s upbringing was pure football. The self-described “football brat” spent most summers as a kid running wild at pro training camps while his dad coached with the Dolphins, Colts, Eagles and Jets, helping the Colts win Super Bowl V. “I was very lucky,” says Idzik. “Back then training camp was eight weeks long, six preseason games, and I would be there for all of it. It was just natural to be around the game and learn its intricacies at an early age. I even got to sneak in some reps with the players during the off-season.”

Moving around so much made it hard for Idzik to lock onto a favorite team. “It was always my dad’s team,” he says, although after sharing a few memories of Johnny Unitas and Bubba Smith, he admits the Colts hold a soft spot in his heart.

Dartmouth was a natural choice. “We had a president who was a math professor—John Kemeny—and an Ivy championship football team,” says Idzik, “so it seemed like a good fit for me.” He found his way to Hanover after a Jets public relations staffer named Ed Wisneski ’72 suggested Idzik check out Dartmouth and the Ivy League. The young receiver was eventually recruited by then-coach Jake Crouthamel ’60. Idzik was part of two Ivy championship teams (1978 and 1981), although a knee injury cut short his playing career. “Unfortunately, I was wearing a red jersey more times than I wanted to my three years on the varsity,” he says. During his freshman year, he says, senior quarterback Buddy Teevens ’79 spent extra time with him and other freshmen in the locker room. “That left quite an impression on me,” says Idzik, “and it’s no surprise now that he’s the leader of that program and has done quite well.”

After graduation Idzik worked for IBM as a programmer and manager. “Quite a natural preparation for the NFL, isn’t it?” he jokes. He resigned when a “dream come true” chance to coach with his father presented itself. That came with the Aberdeen Oilers, a Scottish team with the short-lived British American Football League in 1990. In 1993 Idzik the younger launched his NFL career in the front office of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, eventually moving on to the Arizona Cardinals and Seattle Seahawks before landing with the Jets last year.

The team never fails to draw headlines with its bombastic head coach, Rex Ryan, and recent newsmakers such as Tim Tebow and Michael Vick. The low-key Idzik balances out the hubris. (“We’re side-by-side in this the whole way,” Ryan said earlier this year of his partnership with Idzik.) During a preseason interview the former Big Green receiver seems relaxed. Tanned from the time spent on training camp fields, he fondles the gaudy green-and-gold 1981 Ivy League Championship ring he’s wearing.

How would Idzik the pro GM evaluate Idzik the young college receiver who won that ring? “Skinny,” he says, laughing. “I had good hands and didn’t lack for toughness, but I just didn’t have the girth.”

—Sean Plottner

Alice Gomstyn ’03

Mother Lode

Gomstyn claims she is “pretty much the opposite of the mom you desperately wish you could be.” The mother of two shuns Instagram and promises to “dance on the rooftop drinking sangria” when her boys start school. In the meantime, the former reporter and news producer covers parenting-related topics with a hilarious spin on her blog, Mildly Inappropriate Mommy, and a number of online media sites including Babyzone, Babble, NBCNews.com and The Huffington Post.

Gomstyn, who left a job at ABCNews.com to become a freelance writer after the birth of her second child, considers herself different from the typical mommy blogger in that she combines actual journalism with personal insight. After questioning whether chasing a 2-year-old would keep her in shape, she researched a story comparing the health of parents to non-parents (parents are worse off in multiple ways). Gomstyn also enjoys injecting her personal sense of humor into her blog posts, such as an April Fool’s story announcing her selection by NASA to pilot their MILKMAN device (Modified Infant-Like Kinetic Mammary-Appropriate Nurser) as the first breastfeeding mother in space.

While breastfeeding is a perennial topic, Gomstyn looks to general news stories and parenting coverage on major news sites, including The Washington Post and The New York Time’s “Motherlode” blog, for inspiration. “One of the exciting things about being freelance,” she says, “is that you never know what the next day will bring. I just hope it will bring something funny!”

—Lauren Chisholm ’02

Rich Bloch ’65

Magic Touch

Bloch is one of the country’s most successful labor arbitrators, with clients ranging from the National Football League and Major League Baseball to the U.S. State Department. The attorney can also turn a lighter into a flower, pop bowling balls out of sketchpads and wind a watch without touching it.

When he’s not umpiring labor disputes, Bloch is busy devising effects for his magic performances in the Dickens Parlour Theatre, the intimate 55-seat theater in Millville, Delaware, he built in 2010. Even before opening his own space, Bloch had made a name for himself as one of the magic industry’s best designers of effects, producing tricks for performers such as David Copperfield and Siegfried and Roy through his company, Collectors’ Workshop. It was between meetings for his law practice that Bloch came up with his most ingenious tricks. “I’d run to a phone and call my partner when I had something,” Bloch says. “I just came up with these wacko notions, and he’d say, ‘Yeah, let’s make that happen.’ ”

It was the late Orson Welles who convinced Bloch to perform, dubbing him the “Edison of Magic.” Welles originally contacted Bloch for tips on one of his tricks, which Welles wanted to perform on The Tonight Show. For the next two years Bloch met with Welles monthly to develop tricks and give pointers for the auteur’s public appearances. Bloch, in turn, admired Welles’ entertainment prowess. “It’s hard not to get bit by the theater bug sitting around with somebody like him,” he recalls.

Having two sides to his character is exactly the way Bloch likes it. “These two devotions provide a door I can walk through and take a vacation from one side to the other,” he says. “Finding that little door from time to time is an absolutely wonderful thing to do.”

—Gavin Huang ’14

Lynn Rainville ’93

A Grave Situation

The inspiration for Rainville’s recent book, Hidden History: African American Cemeteries in Central Virginia, traces back to a freshman year research project decoding headstones in the College’s cemetery. Rainville later transcribed more than 2,500 headstones throughout Hanover for her honors thesis before she went on to earn a doctorate in Near Eastern archaeology at the University of Michigan. For the past several years the humanities professor at Sweet Briar College and director of its historic preservation center, Tusculum Institute, has focused her scholarship on historical African American burial grounds. She considers them an often overlooked—and sometimes unknowingly bulldozed—gateway to understanding our cultural past. “These cemeteries are outdoor museums,” says Rainville, who dodged snakes and hunting dogs to catalog the cemeteries in her book. “They contain folk carvings and information about genealogy and slavery.”

According to Rainville, African American cemeteries from the slavery and post-bellum periods differ from modern cemeteries in that they were designed to blend with the natural landscape and feature a variety of markings, from plantings to wooden markers and granite slabs. In slave graveyards the vast majority of headstones bear no inscription (it was illegal for slaves to read or write) but instead may be cryptically marked with flipped letters and Christian and African symbols, which Rainville says represent a “powerful example of resistance.” She finds cemeteries fascinating because they reflect “peoples’ values for their lives.” She also enjoys connecting with descendants through an online database of her work, available at lynnrainville.org.

Lynn’s top tips for cemetery visits

Never lean on a gravestone. “They are not as solid as they look.”

Don’t try to clean a gravestone. “Bleach eats away at inscriptions.”

Treat an epitaph like a page in a book. “Pick apart words, icons and the way they reference a person’s death.”

Watch out for footstones. “For much of the 19th century graves were considered resting places, and footstones marked the foot of the body.”

—Lauren Chisholm ’02

Jamie Berk ’11 and Mostafa Heddaya ’11

Literary Hijinks

Some might say launching a literary magazine today, in a media landscape ruled by blogs and tweets, where the news cycle never ends and the average reader spends 15 seconds on an article page, is foolish. Idealistic at best. Berk and Heddaya believe otherwise.

In 2011 they launched American Circus, an online literary journal dedicated to experimental criticism, personal vignettes and investigative journalism. Writers would be young and talented, most without established professional homes. The journal would be irreverent and serious, a place for lively debates from both sides of the aisle. It was a natural evolution for the pair: Heddaya was president of The Dartmouth Review, while Berk was a Senior Fellow who spearheaded the Dartmouth Independent redesign.

The first issue debuted on Christmas Eve and within the first month earned a Pushcart Prize in nonfiction—for a satirical review of the coat check at the Museum of Modern Art. Since then American Circus has gone inside the headquarters of Egypt’s largest secular party, examined the literati’s response to Hurricane Sandy and investigated the decline of horseracing in a series The Wall Street Journal called “magnificent and elegiac.” The publication feels whimsical (one section is called “Hijinks,” another, “Debauchery”) and simultaneously highbrow. “We didn’t want to just be another literary website,” says Heddaya. “It’s taking some of the best elements of sharp writing and placing them in a context that’s more literary, and taking some elements of the best literary writing and making it sharper and more focused.”

In January American Circus, which Berk and Heddaya fund themselves with help from Litbreaker, makes its print debut. Berk says he hopes “to create writing that resonates and says something. If we can do that, I think we’ll be happy.” Heddaya, ever the businessman, is quick to add: “We hope to have a good subscriber base!”

—Abigail Drachman-Jones ’03

Collin O’Mara ’01

All Natural

“This is the only nonprofit organization I would have left my job for,” O’Mara says in late July, three weeks after becoming president and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation (NWF).

O’Mara, who grew up in Syracuse, New York, spent his career in local government—until now. After studying at the University of Oxford as a Marshall Scholar and, later, the Syracuse University Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, he became the clean tech strategist in San Jose, California, where he designed the city’s Green Vision program. In 2009 he was tapped to lead the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, making him the youngest state cabinet official in the United States.

Then NWF called. “It’s an opportunity to make wildlife and the real outdoors more relevant in the technology age, and connect with people in a way that has tremendous benefits, whether it’s health and wellness or academic performance,” O’Mara says. NWF is the country’s largest and oldest conservation group. Its work, which emphasizes grassroots and broad-base outreach and education, is especially important today, he says, when the average child spends around 50 hours a week in front of a screen and less than 30 minutes a week in unstructured outdoor play. O’Mara plans to change that ratio.

“There’s a quote I use: ‘You only conserve what you love, only love what you understand and only understand what you’re taught,’ ” he says. “If folks develop an undying love for the outdoors, if they’re invested in it, they’re more likely to defend nature for current and future generations.”

—Abigail Drachman-Jones ’03