John Chittick ’70

On a Global Mission

“Dr. John” gives teens the tools they need to fight HIV/AIDS in their communities.

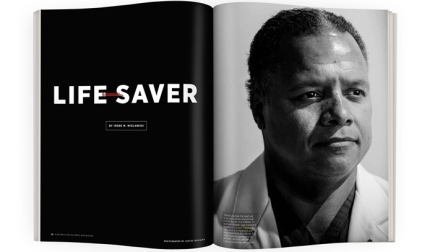

Since 1994 Chittick has fought the spread of HIV/AIDS globally, first through an educational website he developed and, since 1997, as founder and executive director of TeenAIDS PeerCorps. Through the nonprofit he has traveled around the world to perform HIV outreach and education, often in communities where individuals who contract HIV are highly stigmatized. He estimates that TeenAIDS volunteers have trained more than 300,000 peer educators to spread information about HIV prevention, treatment and testing resources in 90 countries.

When the AIDS pandemic exploded onto the public scene in the early 1980s, Chittick ran a postcard company and owned a contemporary art gallery on Charles Street in Boston. But as the disease took hold, claiming the lives of friends, employees and colleagues of all backgrounds, he was compelled to do something. He also had a premonition: AIDS would affect people outside the demographics that experts were focused on at the time. Chittick sold his business in 1992 and began to pursue a doctorate in adolescent psychology from the Harvard School of Education. His research focused on models of HIV education and the efficacy of prevention programs among teenagers—despite chiding from higher-ups, including his dissertation advisor, who did not believe that young people were at risk. “He told me, ‘Teens don’t get it. It’s only gay people. It’s only Africans,’ ” Chittick says. “I predicted a global pandemic of HIV among sexually active teenagers.”

He was right. In 2010 the United Nation’s Joint Program on AIDS reported that 15-to-24-year-olds accounted for 42 percent of new HIV infections in people aged 15 and older. Chittick insists that thoughtful and comprehensive education is the answer. “These kids are getting it because they’re ignorant of the facts,” he says. “They’re not given medically accurate information.”

The peer-education methods used in TeenAIDS initiatives are based largely on Chittick’s Harvard research, but he says that on-the-ground experiences have shaped his philosophy on working with young people. For example, he began testing youth for HIV publicly in 2012 after struggling for years to convince teens to take advantage of private testing resources at local clinics. “The idea is that there’s no shame, there’s no stigma, and they’re able to test their own bodies,” he says. TeenAIDS uses oral swab technology at its live testing events, where teens receive HIV testing among their peers and often in front of the media. “They take selfies, they post pictures of the events on Instagram,” he says, “so they’re passing this message on through social media to their friends and peers.”

After more than two decades of extensive travel, which included walking almost 30,000 miles as part of his “Global Walks” in parts of all the world’s continents except Antarctica, Chittick says he will take one final driving tour across the United States in early 2017 before relocating from Fitchburg, Massachusetts, to a remote Micronesian coral atoll in the Pacific. There, in what he describes as TeenAIDS’ “final and most innovative step,” he’ll establish Atoll Academy (teenaids.org/atoll-academy/), a free school that will offer college prep skills as well as AIDS prevention training. “It is critically important that teenagers living in the remotest locations with few resources become an integral part of a life-saving world mission,” he says. “These young people have the ability to spread knowledge. They just need the proper information.” —Savannah Maher ’17

Mateo Romero ’89

“A Meditation”

During his college years, contemporary artist Romero would take trips to the Santa Fe (New Mexico) Indian Market, the world’s largest Native American arts show. The event provided not only creative inspiration but also a deeper connection with Romero’s ancestry, since his painter father, Santiago, grew up nearby as part of the Cochiti Pueblo tribe. “It was this really intense thing,” he says. “I remember thinking, ‘This is where I belong.’ ”

Now Romero lives on the Pojoaque Pueblo reservation in New Mexico with his wife and children, having established a reputation for vibrant paintings and mixed media pieces that portray Southwest Native culture. Many compositions use thick layers of paint to depict ceremonial dances and feast-day celebrations, sometimes incorporating historical images or Romero’s own photography. Others—including a “Bonnie and Clyde” series that substitutes Native youngsters for the infamous outlaws—comment on subjects such as violence and alcohol abuse. His work is in private and public collections around the world, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and the Hood Museum. Bloom, part of a series he modeled on students as they danced at the Dartmouth Pow-Wow, hangs in the Hanover Inn. “Painting for me has the potential to connect people to each other,” he says. “It’s not just a Native thing. It’s a human experience.”

Raised in Berkeley, California, Romero is a third-generation artist: His grandmother was a ceramicist and older brother Diego is a prominent potter. Romero learned to draw by tracing comic book covers, particularly those by Marvel illustrator Jack Kirby, but entered Dartmouth intending to major in architecture. Studying under artists Ben Frank Moss and Varujan Boghosian helped change his mind. Romero, who also has an M.F.A. in printmaking from the University of New Mexico, explains that the desire to paint runs deep. “I actually need to go into my studio,” he says. “It’s like a meditation for me.” —Heather Salerno

Jayne Conroy ’80

Fighting the Good Fight

As one of the nation’s top civil and personal injury attorneys, Conroy is used to David-and-Goliath showdowns. Throughout her 30-year career, she’s secured billions for her clients in cases against conglomerates such as Toyota for unintended acceleration malfunctions, BP Oil for the Deepwater Horizon spill and Pfizer for drugs Bextra and Celebrex. “When you’re going up against companies like this, there’s a lot of firepower being thrown at you,” she says.

Most recently, Conroy scored a $502- million verdict against Johnson & Johnson for five plaintiffs who are among 7,000 claiming that a popular hip replacement device is defective. In court, the trial team introduced shocking evidence that the company lied in medical testing and marketing of the implants. “That stunned me,” she says. “I’ve been doing this a long time, and I’m quite cynical about a lot of things, but I’ve never seen this type of fraud.”

A founding partner of the nationwide law firm Simmons Hanly Conroy, she also represents about 6,000 family members of 9/11 victims in long-pending claims against financial sponsors of the terrorists, including the Saudi Arabian government. In 2013 Conroy achieved a $12-million settlement for 24 boys sexually abused at a Haitian school for street children, established and supervised by Fairfield University and the Society of Jesus, against which more than 100 new complaints have since been filed. “It’s heartbreaking,” she says of such cases.

Raised outside Boston, Conroy had planned to go to med school post-Dartmouth. She shifted gears after taking a summer job at a law office, where she assisted with medical-related litigation. These days, she still gets a thrill from devising winning strategies to help injured parties. “It’s a pretty amazing rush,” she says. —Heather Salerno

Brian Schott ’93

Backwoods Lit

Interviews with former NFL quarterback Drew Bledsoe or comedian David Letterman might be the last thing you’d expect to find in a literary magazine known for the literature, art and photography of mountain culture, but when Schott founded Whitefish Review in 2007 he wanted to surprise readers. “I didn’t want it to be some high-brow academic journal,” he says. “Our goal is to speak with smart, engaging people, but also people who care about place. The way Letterman talks about his love of Montana and what the land does for him was a really powerful part of that interview.”

During the past decade Whitefish Review—which focuses on the power of open spaces and the independent spirit of people living in wild places—has published interviews with Tom Brokaw and John Irving and original work from Rick Bass and William Kittredge. The December 2015 Letterman issue featured six stories later nominated for the Pushcart Prize: Best of the Small Presses.

Schott always had a literary streak. After graduating from Dartmouth with a degree in literature and creative writing, Schott moved to Vail, Colorado, where he juggled a magazine internship and freelancing with gigs at a ski shop and golf course. “I chose jobs that wouldn’t consume my brain power too much because I wanted to concentrate on my writing.” Then he took it a step further: He moved about 20 miles north of Whitefish, Montana, and spent four months living in a one-room cabin. He wrote every day, explored, read Walden: “It was very deliberate living.” Years later he earned his master’s in liberal studies at Dartmouth, where he was inspired to launch Whitefish Review. “We’re trying to create a little buzz,” says Schott. “We want to try to blow it out of the water.” —Abigail Drachman-Jones ’03

Lori Florio ’80 & Emily Vitale ’80

Design Duo

Florio and Vitale, close friends since they moved to New York City after graduation, seized on the idea for clothing line Prismsport by identifying a seemingly small frustration: They were sick of spending all their time in blah, monochromatic workout clothes. “We kept seeing ourselves and our friends looking like we’d just come from the gym,” Vitale says. “At a certain point we didn’t want to look that way all day, so we needed to create what wasn’t there.”

Vitale and Florio had left the 9-to-5 world to raise children and pursue more flexible work. As serious athletes—both women played in U.S. Tennis Association tournaments for years, and Florio is a yoga instructor—they wanted clothes that stood up to tough workouts but made a fashion statement. The result was Prismsport, which quickly gained a cult following for its bright, dramatic prints made in high-performance fabrics. Founded in 2012, the company makes about 30,000 items per season and sells to places such as online retailer Shopbop, Equinox gyms and Nordstrom. Each print is subjected to an in-house “thigh test” to make sure patterns still flatter when stretched over curves.

The company seems to have tapped into the zeitgeist. “People are dressing more casually, which is particularly fueled by so many people now working at home and working remotely,” Florio says. “The idea of clothing that can transition seamlessly from one part of your life, or one part of your day, to the next part has really made this take off.” —Kaitlin Bell Barnett ’05

Steven Fox ’00

Classical Rediscovery

Classical music spans centuries and nations, but contemporary performances and recordings represent just a fraction of what was written. Fox has made a name for himself finding and conducting some of these overlooked classical gems. He discovered some of these compositions while on one of the College’s post-grad Reynolds scholarships, assembling what would become Musica Antiqua St. Petersburg, an orchestra devoted to early classical music.

“There was a golden age of Russian music from the 18th century that had just been forgotten,” says Fox, a music major whose interest in Russian compositions was stoked on a Dartmouth foreign study program and while staging performances of Russian music as a Senior Fellow. Among the lost works was the first symphony written by a Russian composer, which Fox found tucked in a private archive in Rome and presented in London, New York and St. Petersburg.

More recently, as conductor of the Clarion Music Society in New York—which, like Musica Antiqua, performs on period instruments authentic to the composer’s time—Fox has rehabilitated another great, but forgotten, Russian composition. Maximilian Steinberg composed Passion Week as a piece of Russian Orthodox choral music in the 1920s, when the Soviets banned all religious music. After garnering critical accolades with the New York premiere, Fox conducted the work in October for the first time in its country of origin.

Finding great works that have fallen through the cracks is exciting, but challenging. “You have to be able to decipher between the mediocre or good works and the great works,” Fox says. “I’m looking for great works because I think life is too short to do anything less.” —Kaitlin Bell Barnett ’05