Russell Wolff ’89, Tu’94

The Mentor

ESPN executive VP embraces the sporting life around the globe.

Every September for the past 12 years, Wolff has trekked up to Hanover to deliver a speech to incoming Tuck students called “What’s Your Dream Job?” It’s no coincidence that he has clearly found his.

As EVP and managing director of ESPN International in Connecticut, Wolff oversees a team that spans 61 countries. “I love my job because no two days are the same,” he says. “One minute I can be focused on redesigning a cricket app for India and the next minute I’m looking at five-year financial plans for one of our business initiatives in Latin America. Any given week could be board meetings for investments that ESPN has around the world, office visits to our various operations in Mexico City, London, São Paulo, Sydney, Bangalore, and attending sporting events with clients.” It means he spends almost more time traveling than he does at home, but he also has an open invitation to every hot ticket athletic contest imaginable: Wimbledon, the Masters, the Stanley Cup. This August he’ll fly to Rio for his 15th Olympic games. “Almost everyone I talk to says, ‘Now, that’s a dream job,’ ” says Wolff, “but I just kept following my heart and doing things I was interested in and excited about. I also think I got very lucky along the way.”

Choosing between Tuck and Harvard business schools when he was accepted to both was one of those decisions the government major let his heart decide. “I did the cocktail party test,” says Wolff, who worked for Leo Burnett for three years before going back to school, “where I’d give a person one or the other outcome and see how they felt. Everybody I told about Harvard was really excited about that, but I noticed that when I told people I got into Tuck, I was the one excited.” M.B.A. in hand, Wolff took a sales position with MTV networks before moving to ESPN, where he’s worked for 19 years. His early years with the sports network were spent in Hong Kong and Singapore. He moved overseas sight unseen, “which I don’t recommend to anyone,” says Wolff, whose wife, Patty Frank Wolff, Tu’94, got a transfer there at the same time from her employer, PepsiCo. “Still, it was the greatest life experience for us,” he admits. His time in Hanover had a big impact on him, too, which is why he volunteers for Dartmouth and Tuck. A passionate member of the Alumni Council, he was elected president last year and begins his tenure this summer.

Wolff lives with Patty and sons Spencer, 12, and Michael, 14, in Mamaroneck, New York. He dedicates much of his free time to the New York Sled Rangers, a sled hockey program he helped start in 2012 for physically disabled youth in and around New York City. “It’s cool because you get to see these kids who are in walkers and wheelchairs suddenly go very fast on their own,” says Wolff, whose son Spencer has cerebral palsy and plays on the team.

After his trip to Rio, he’ll be back in Hanover to speak to the new arrivals at Tuck. Although he tweaks his speech each year with new anecdotes from his family and work life, his key message to the students doesn’t change. “It’s about getting in touch with who they are, what they really want to do and what they can do to get there,” he says. “I’m not there to say, ‘Do what I did.’ I’m there to say, ‘Be happy.’ Because the idea of toiling away for your whole life at something you’re just okay with? That isn’t good enough.” —Jennifer Wulff ’96

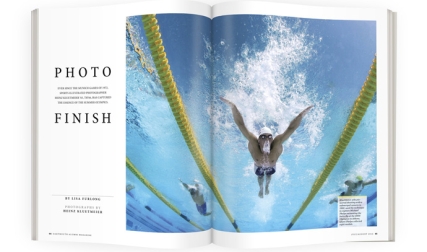

Matthew Heineman ’05

Shooting the Truth

Some documentary filmmakers start their projects knowing what they want to convey to audiences. Heineman tries to do the opposite, starting with a blank slate and chasing the story wherever it takes him. For his documentary Cartel Land, which was nominated for a 2016 Academy Award, that meant following citizen militia groups in Arizona and Michoacán, Mexico, as they mounted armed resistance campaigns against powerful and ruthless Mexican drug cartels.

Cartel Land is Heineman’s third feature documentary. Still, the history major found himself filming things he never could have imagined: scenes of torture, “countless scary shootouts,” testimonials from survivors of cartel violence, and open-air meth cooks operating in the dead of night. “I think the beauty of filmmaking is exposing people to a world they wouldn’t otherwise get to see,” Heineman says. “I felt a huge duty and obligation to show these things—to put myself in these situations, to keep going down there until I got access to these moments.”

Securing that access required flying from New York City the instant a promising lead emerged—he kept a “go” bag packed at all times—and, crucially, getting “buy-in from the top” of both vigilante movements. He’s applied that second strategy to current projects, which include a feature documentary planned for release in 2017 (about which Heineman declined to give specifics), a documentary TV series and his first narrative film. “Part of why I love what I do,” Heineman says, is that “I get to explore the depths of humanity in ways I wouldn’t otherwise get to do.” —Kaitlin Bell Barnett ’05

Stella Maria Baer ’03

Out of This World

When NASA released its historic up-close photos of Pluto last summer, Baer was inspired. “Seeing those images taken by a spaceship from billions of miles away was mind-blowing,” says the artist, who decided to paint watercolors of the dwarf planet and its moons. The resulting work is typical of Baer’s unique vision—depicting celestial bodies in the earthy desert colors of her native New Mexico. Though a professional artist for only five years, she’s already gained attention: With 165,000 Instagram followers, Baer has sold pieces all over the globe and her work has been featured in The New York Times, Time and Scientific American.

The daughter of a weaver and a gallery owner, Baer rebelled against the art world as she grew up in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and studied philosophy at Dartmouth. She didn’t pick up a brush until she attended Yale Divinity School, where graduate classes sparked her interest. “For a long time my paintings and drawings were a secret practice,” she says. Baer sold her first paintings at a student show in 2011. Word spread about her quirky concept—animals riding other animals—and she spent the next two years working on commission. Burned out in 2013, she took a road trip through the Mojave Desert. “There was something about the colors of the rocks and sands,” she recalls. “It was like I was seeing them for the first time even though I’d grown up in that part of the country.”

She began painting moons after seeing a photograph of the 2014 “blood moon” eclipse. Since then Baer has created more than 100 celestial canvases, incorporating the pinks, tans and grays of the Southwest. A recent move to Denver—where Baer had a show in May—may lead to a new perspective. “It’ll take some time to figure out how it will bleed into my work,” she says. “But it’s definitely a landscape I’ve been thinking about.” (View a slideshow of Baer’s work.) —Heather Salerno

Anna Jaeger ’93

The Tech Supporter

After she graduated with a major in drama, Jaeger worked for a nonprofit that provided services for those with disabilities. She did well but burned out. “I get too emotionally involved doing direct support work,” she says.

Now the San Francisco resident channels her passion to do good in a less personal, but perhaps more wide-reaching method. As chief technology officer of Caravan Studios, Jaeger builds mobile apps to address pressing social problems. One of her projects has been creating Safe Shelter Collaborative, which connects victims of domestic abuse with shelters. The app is designed to avoid the stressful, inefficient process victims often face when they attempt to find safe housing. Frequently facilities lack rooms or resources to effectively treat a victim, who then has to start calling around to find space elsewhere. Because providers need to know whether they have the proper treatment tools, victims have to recount their abuse with each call. Jaeger’s app addresses this problem with a brief questionnaire that sends information to all nearby shelters and quickly connects a victim with the right facility. In a recent pilot program, Safe Shelter reduced the average time to connect a victim with an appropriate shelter—which Jaeger says previously took from two to 10 hours—to just seven minutes.

This is only one of Jaeger’s many projects. Another app, Range, helps underprivileged youth find free meals in summertime, when they can’t get food at school cafeterias, Another app, 4Bells, helps volunteers organize and tackle the most time-sensitive tasks after areas are hit by natural disasters. “They are all just examples of how technology and data can make a big difference in a person’s health, safety and emotional well-being,” says Jaeger. —Keith Chapman, Adv’12

Stephanie Hogan ’02

In Search of Fresh Air

Concern for the planet has been part of Hogan’s life for as long as she can remember: She grew up outside Cleveland, where the Cuyahoga River—a waterway so dirty it caught fire in 1969—was practically in her back yard. “I wasn’t around when that happened, but I couldn’t help but know all about it,” she says. “It sparked much of the environmental movement in the 1970s.”

That infamous fire also led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, where Hogan now works. One of the youngest attorneys in the EPA’s Office of General Counsel, she plays a key role in enforcing the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule, a provision of the Clean Air Act that protects citizens from harmful power-plant emissions that drift across state lines. The agency says this regulation will help prevent tens of thousands of premature deaths, heart attacks and other illnesses in the United States, including hot spots such as New Haven, Connecticut, where 93 percent of ozone pollution has been found to come from out of state. “It has a direct impact on people’s health,” says Hogan, who majored in environmental studies and English at Dartmouth. “If a family wants to go to the park, they don’t have to worry about inhaling pollution that’s going to cause an asthma attack in their child.”

Hogan helped the government defend this policy before the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld it in 2014, but there’s still more to do—including new regulations that reflect tougher EPA standards. Hogan’s efforts have been noticed: She was a finalist last year for the Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medal, given to federal employees for outstanding accomplishments. “I always wanted to do something that felt like I made a difference in the world,” she says. “It’s certainly humbling to know that the work we do here has such an impact.” —Heather Salerno

Alex Tonelli ’06

Life Changer

Tonelli grew up fast. An orphan raised by his grandparents, he was couch surfing with friends by middle school and “not on a great track,” he admits. Tonelli also played hockey, and one day an athletic trainer took him aside to tell Tonelli he had potential, not so much in hockey but in life in general. The trainer recommended some boarding schools Tonelli should apply to and suggested possible scholarships. That conversation changed his life, Tonelli says, and put him on a better path. He enrolled at the Hotchkiss School and then earned a government degree at Dartmouth and an M.B.A. at Stanford. It’s safe to say Tonelli is well on his way: He’s a serial Silicon Valley entrepreneur, having cofounded Funding Circle—a lending company valued at more than $1 billion—and now works as a partner in entrepreneurial project manager Endurance Companies.

Sipping coffee in a San Francisco café, Tonelli compares one’s life path to roads. Once you’re on a good highway, he says, you’re more likely to be successful. “But it’s not the highways that are broken. It’s the on-ramps.” Last fall Tonelli started Vocate, a company he hopes will offer on-ramps for young people. Vocate is an online platform that connects students with internships and entry-level jobs. “Our online process takes students through levels where at each point they work through activities in three areas—self-understanding, skills, professional development. At each new level they ‘unlock’ employers,” he says. The company launched at Dartmouth and has already placed 500 students and recent graduates from three schools. Tonelli hopes to add another dozen schools to his roster by the end of the year. —Keith Chapman, Adv’12