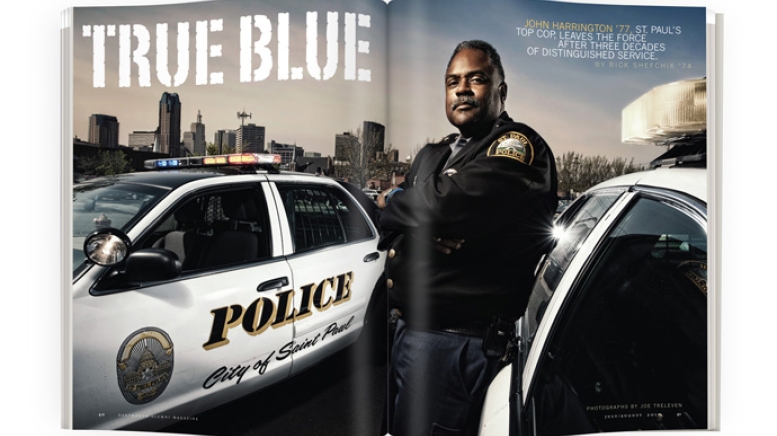

Inside the office of outgoing St. Paul, Minnesota, police chief John Harrington are all the expected plaques, coffee mugs, badges and assorted gifts and trinkets accumulated during a 33-year career in law enforcement. There’s also a set of ceremonial samurai swords.

“I picked up my first bit of Japanese and Chinese martial arts as part of a Dartmouth club,” Harrington says. “I studied judo and karate there. My love of things Asian probably started in Chicago with some exposure I had at De La Salle Institute, but my love of Japanese martial arts really started in Hanover.” He “really blossomed,” he says, while studying with professor Hans Penner, who taught Sanskrit and Indian Buddhist studies.

A native of Chicago’s South Side, Harrington grew up dreaming of being a police officer like his father, a Cook County deputy sheriff. “My best friend’s dad was a Chicago cop,” Harrington explains. “Before my dad became a cop he had run a bar. On those good days when I got to hang out at my dad’s tavern you’d see the Chicago cops walk in who were literally, physically, giants. I’m a skinny 14-year-old kid and these 6-foot-3, 6-foot-4 block-out-the-sun guys would walk in with two guns on and big leather coats and sit down on the back porch and talk to my dad.

“These were the old days when it was okay to be seen but not heard. I’d kind of hang out around where the grownups were and I was smart enough to be very, very quiet. I’d just sit there listening to them talk about kicking in doors and chasing people across the L tracks. I was hooked. This was better than TV.”

Harrington graduated from Dartmouth with a degree in East Asian studies and religion, and a minor in Chinese, and began looking for cop jobs in the big cities. No one was hiring. He briefly considered using his Asian studies to do overseas law enforcement work, perhaps with the CIA, but decided his spoken Chinese was not strong enough.

“New York went bankrupt,” Harrington recalls. “They laid off 2,000 cops in 1975 and 1976, and everywhere I applied my senior year was flooded with New York detectives. I’ve got this wonderful Ivy League degree and they’ve got 100 collars they made last year. Guess who got the job?”

Finally Harrington found a job in St. Paul, at least in part because a Minnesota judge had ordered the department to hire more black officers. There were just six black cops on the force at the time.

After making it through the department’s 21-week academy there was just one impediment keeping Harrington from becoming a cop: his diploma. His high school diploma.

“I told them, ‘I sent you my college diploma.’ They said, ‘No, what we require is a high school diploma.’ ” Harrington had to call his mother and ask her to mail him a copy of his diploma from De La Salle.

Assistant chief Matt Bostrom, who joined the force a few years later and now holds a doctorate in public administration, understands the skepticism an educated cop like Harrington had to face.

“I had conversations with some of the older officers, who’d say, ‘What do you need the degree for? You need street smarts, not book smarts,’ ” Bostrom says. “When [Harrington] arrived he had a degree at a higher level than what’s required now. Today, even though it’s not a requirement that you have a four-year degree, it’s the rarest occasion that someone shows up at our door who doesn’t have a four-year degree, and several have completed a master’s or are working on one.”

Harrington, who in 1985 earned a master’s in curriculum and instruction from the University of St. Thomas, demonstrated repeatedly on his rise through the ranks the value of his book smarts.

When St. Paul became one of the major U.S. resettlement locations for Hmong immigrants in the 1980s Harrington played a major role in helping them adjust. “Pieces of their culture and language are very definitely tied to the Chinese, and other parts more tied to the Vietnamese,” he says. “It was easy to make that kind of cultural contact, to be a good bridge for them here.”

Harrington was also instrumental in training new officers and designing new programs. In the late 1990s he initiated and facilitated joint training sessions between the St. Paul police and fire departments, a then-unheard-of idea.

“In public safety prior to 9/11 police did their thing, fire did their thing, emergency medical services did their thing,” says Al Bataglia, who retired from the St. Paul fire department in 2003 as interim chief. “Everybody had specialized areas and you didn’t cross borders into another person’s territory. What we found out was no one department could do anything alone. John was one of those guys who’d find out what the fire department’s job was and make sure that they found out what law enforcement’s job was. He was very innovative.”

Harrington served as the department’s personnel and training director when, in 2000, he was put in charge of St. Paul’s western district, an operational command he’d been hoping for. There he implemented an innovative and effective antidrug project that helped reduce juvenile crime by 65 percent and narcotics offenses by 70 percent in its first year.

The assignment also gave him a big boost toward becoming the city’s next chief, a position he hadn’t expected to get. He’d applied unsuccessfully for the vacant Minneapolis police chief’s job in 2003. But a year later, when then-St. Paul Chief Bill Finney announced he wouldn’t seek another term, St. Paul Mayor Randy Kelly named Harrington as Finney’s replacement.

How did he feel? “Proud and overwhelmed,” Harrington says. “I thought, ‘Now I’ve got to pick people. How do I run this place? I don’t want to screw it up.’ ”

He didn’t. Every category of crime except commercial burglary has declined on his watch, and a new antigang project has resulted in the lowest number of gang assaults in years. His campaign against domestic violence has produced dramatic results: an average of 5,000 fewer cases each year. Technology upgrades under Harrington put cameras on the streets and updated radios and closed-circuit monitors in cars.

“In my mind there are 30 people out there who would be dead if we’d just continued business as usual,” Harrington says. “I think my worst year as chief we had 27 or 28 homicides. We ended up last year with 14.”

Perhaps best of all, thanks in part to federal stimulus money, St. Paul added 24 officers to the force in January. Another 20 are expected to join in the fall. “I said when I took the job I would probably do one [six-year] term,” Harrington says. “I made the commitment that if the place was a mess, if we were in crisis, I wasn’t going to abandon ship.”

Despite the positives the department’s inability to increase the number of black cops on the force beyond the current total of 60—out of a force of 600—frustrates Harrington. When he took over as chief the department goal was to have blacks make up 10 percent of the force, equal to the percentage of blacks in St. Paul. While the percentage of blacks in the city has risen, the percentage of black cops remains stuck. “It’s been a very difficult nut to crack to try to find young black men and women who want to be in this line of work, who want to go through all of the hoops that the state requires,” Harrington says.

He also wants to see the department further develop “intel-based” policing, to the point where officers can use in-car computers to access an array of databases. “They will have the technology at their laptop command so they can actually dial up pictures of the bad guys as they’re running away from the scene,” says Harrington.

But that’s for the next chief. Harrington is ready to move on. He was one of three finalists for the New Orleans police chief job this spring, then in late May acknowledged he was considering a run for the Minnesota State Senate. Regardless of his decision he will not be idle. He serves on the boards of several local institutions and he’s thought about teaching or pursuing policy studies. He’d like to work on homelessness issues. He’ll spend more time with his family, which includes going to his granddaughter’s hockey games. (Harrington played as a kid in Chicago and briefly tried out for the Dartmouth freshman team until, he says, “I found out what real hockey looked like. I was out of my depth.”)

Yet the chief suspects part of him will always be that kid who listened raptly to his father talking shop with fellow cops.

“I’m not quite sure I’ve got the cops and robbers out of my system yet,” Harrington says. “There’s a piece of me that hasn’t ever totally got rid of the idea that the best job in the world is working the midnight shift with a really good squad car and a good partner and going as fast as you possibly can to the next hot call.”

Rick Shefchik’s third novel, Frozen Tundra, was published in June by North Star Press.