Tales From the Trail

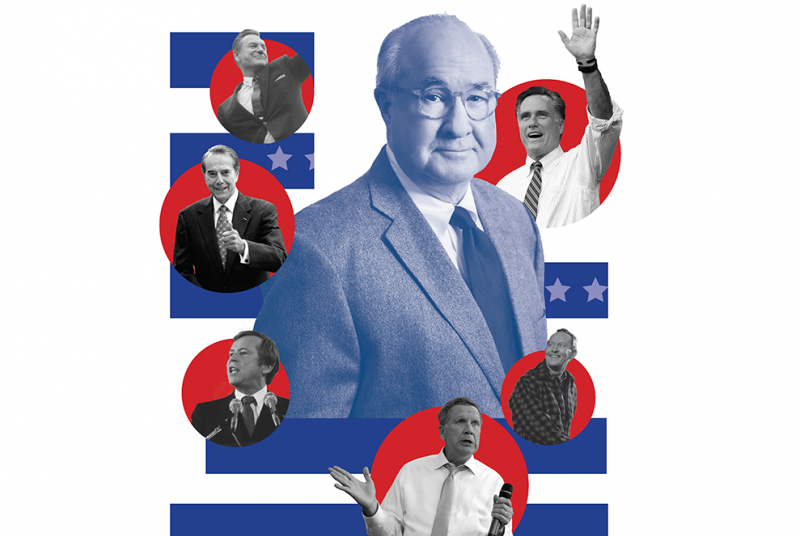

Tom Rath may be the last of a classic New Hampshire political breed—the savvy, chatty, Republican insider from the golden days of the First in the Nation presidential primary. A government major, Rath has been promoting GOP candidates since he was a freshman working on the 1964 primary campaign of N.Y. Gov. Nelson Rockefeller ’30.

Rath’s title is usually “senior advisor,” a catch-all that can include scouting a town hall or restaurant the day before an event, advising on strategy, offering last-minute advice to a candidate, or bantering with reporters. “I frequently was part of the debate spin groups. And I spent a good deal of time with the candidate in the car,” says Rath, 75, who now chairs Rath, Young and Pignatelli, a law and political consulting firm in Concord.

New Hampshire was where the road to the White House really began, where everyone had to bundle up, knock on doors, tour strip malls, and hang out in the Sheraton Wayfarer lobby in Bedford. From 1952 until 1988 no one was elected president without first finishing first in New Hampshire. “Tom knew how to get things done. He doesn’t get tied up with a lot of ideological crusades,” says Wayne MacDonald, who has served three stints as state Republican chairman. “He’s very pragmatic, and in the end, every campaign really comes down to that.”

Rath is still a pragmatist, but he’s wistful for the old days, when “the candidates knew your kids” and he would talk about baseball box scores with George W. Bush. Bush, an owner of the Texas Rangers, once asked Rath what Bush’s biggest mistake had been. “Sammy Sosa,” Rath snapped back instantly. The Rangers traded young Sosa away in 1989, and he went on to become one of the game’s premier sluggers.

Rath was the state’s attorney general, an appointed position, from 1978 to 1980, a job that for many has been a stepping-stone to the U.S. Senate or governorship. He served as the state’s Republican national committeeman from 1996 to 2000 and 2002 to 2007. But he had no interest in running for office. “I saw the price people had to pay,” he says. Married and the father of two, he recalls how his daughter, when she was on her high school soccer team, once had a terrible dream: She got to her game without her shin pads and shoes. But her dad brought them. “That was it,” Rath says, laughing. “I really like being with my family.”

Coffee Klatch

In 1964 Rockfeller found himself facing an unexpectedly tough challenge: the surging GOP conservative movement, led by Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater. Another problem: Rockefeller had divorced his wife in 1962 and married Happy Murphy, 18 years his junior, in May 1963, a month after she divorced her husband. That didn’t go over well in steady-habits New Hampshire.

“To a lot of people, he had the temerity to divorce and remarry,” Rath recalls. The Manchester Union-Leader, known for its bare-knuckles attacks on moderates such as Rockefeller, “brutalized him every day.” But, says Rath, Rockefeller “was a gregarious campaigner.” He would dive into crowds and gently grab elbows to talk with people.

The freshman’s job was to make sure the coffee was hot when the candidate arrived at an event and that 35 to 40 people were on hand. One memorable moment came during an appearance Rath helped organize at the Bristol community center. Rockefeller, he says, “had these big horned-rim glasses, and he stuck one of the arms into his cup and stirred the coffee. It was an icebreaker. It was something everyone there had done.”

Comfort Food

Bob Dole was the U.S. Senate Republican leader, brimming with insider know-how and generous donors, but he was facing Vice President George H.W. Bush in the state’s 1988 primary. Dole had momentum; he had won the Iowa caucus, and polls showed him in a virtual tie with Bush in the campaign’s final days. A decorated World War II veteran, Dole was warmly received on the campaign trail, joking and bonding easily with veterans and small-town folks.

But when Dole was asked to pledge not to raise taxes, he hesitated. He had pushed three tax increases through the Senate in the 1980s, which helped stabilize Social Security and curb runaway federal deficits. “Dole could never get the New Hampshire pledge out,” Rath says. “We went round and round with him. The strain of it was brutal.” Five days before the vote, he and other aides set up a studio in Merrimack where Dole could shoot an ad saying he wouldn’t raise federal income tax rates. “He was tired. He was short-tempered,” Rath recalls. They did 15 takes. “He just couldn’t get it right. That night turned out to be the last night we were close to Bush in the polls.”

On the last day of the race the team was arranging lunch for the candidate as he toured polling places. “Dole called and said, ‘Don’t do lunch. Is there a Kentucky Fried Chicken in town? Get me a bucket of chicken and ice cream,’ ” says Rath.

White House Invitation

Rath was a big fan of Sen. Howard Baker, the genial Tennessee senator who challenged President Nixon during Watergate. Baker ran in the 1980 primary but was buried by Ronald Reagan in New Hampshire. By 1982 there was talk that Reagan, who would be 73 in 1984, wouldn’t seek another term. Baker’s camp summoned Rath to Washington, D.C., but the senator decided not to run. Then in 1987, as Reagan’s second term was winding down, the political stars seemed ready to align. Baker had left the Senate in 1985 a widely respected figure and was 61. He had a loyal network of friends and donors and a PAC. Rath and the team were ready to go.

Then Reagan called Baker. The Iran-Contra scandal had the White House in disarray. Rath says that Baker told him, ‘Tom, there are two calls you can get from the president. One is ‘Can you do this?’ and the other is ‘I need you to do this.’ ” Reagan needed Baker to become chief of staff and get things running smoothly.

Two weeks later, Rath says, he visited Baker in Washington. “He brought me to the West Wing. He said, ‘Are you ready to come here and work?’ I said, ‘What would I do?’ He said, ‘How do I know? I’ve only been here three days.’” Rath laughed—and declined.

Plaid Fad

Lamar Alexander was another pragmatic Republican with a sterling resumé: governor, secretary of education, Southerner, easygoing, personable. He decided he would walk the whole state as he pursued the presidency in 1996. He walked about 6 or 7 miles each day, and then someone in his entourage would put an X where he stopped. If it snowed and no X could be seen? “We also took a picture,” says Rath. “I’d get him started and get in the car and go to the next event.”

Rath says Alexander was the logical alternative to frontrunner Bob Dole. But into the race came magazine publisher Steve Forbes, who spent tens of thousands of dollars on ads.

Another pitfall for Alexander: “He had worn the plaid shirt when he was campaigning in Tennessee and told us it was very much who he was,” Rath says. But for circumspect New Hampshire voters, who weren’t that familiar with Alexander, the shirt “distracted people from what he was saying.” Alexander finished third and was gone from the race two weeks later.

No Nonsense

In 2007 Rath joined Mitt Romney’s team. “For a guy who’s been around politics all his life, he really doesn’t like the rough and tumble,” Rath says of the former Massachusetts governor, now a U.S. senator from Utah. Romney “is as smart as anybody I’ve seen,” Rath says. When Boston’s Big Dig tunnel ceiling collapsed in 2006, Romney “had a role for everybody. He was interested in designs and plans.”

On the campaign trail, though, he proved to be too methodical, Rath says. Romney usually stuck to his script, but in the 2008 primary he faced Sen. John McCain, a master of informal campaigning, whose “Straight Talk Express” bus rolled through the states with eager supporters waiting at every stop for unscripted conversation. Romney “didn’t do a lot of ad-libbing,” Rath recalls. There would be no rollicking campaign bus, no stirring coffee with his eyeglasses. “There’s a dignity about him,” says Rath. “He didn’t like to do stunts.” Romney lost to McCain and a month later left the race.

There’s Always Tomorrow

After the primary, McCain returned to New Hampshire to meet with the delegation that included Rath, a Romney delegate, in a Manchester airport hangar. McCain came over to talk. “He said he respected the work I’d done over the years,” says Rath.

That’s how politics should work, he says, recalling how he accompanied U.S. Supreme Court nominee David Souter to Washington, where he faced a tough Senate Judiciary Committee hearing. The chairman was Joe Biden, then a Democratic senator from Delaware. Times were partisan, but “Biden was amazing,” Rath says. “He set up a little anteroom, came over and said, ‘I’ll set up some coffee. Let me know when the judge needs a break.’ ’’

Rath hoped Romney would run again in 2016. “I was prepared,” he says. “I had conversations with other campaigns including Jeb [Bush] and others about possibly going with them, but I was with Mitt until he finally said no.” Rath had all but decided to sit that one out until Ohio Gov. John Kasich called. “We got along well. He loved to talk about politics and liked hearing stories from other campaigns,” says Rath, who became a senior member of Kasich’s strategy team.

Rath is not a fan of Donald Trump. “The more I saw of Trump and his team, the more I was convinced he would be bad for the country,” he says. Kasich came in a distant second to Trump in the New Hampshire primary.

What about this year? “I would have been with Kasich had he gone,” Rath says, “but could not have advised that there was a realistic chance.”

The future is cloudy. “I would like one way or another to play again in 2024,” Rath says, but not with Vice President Mike Pence. “Mitt still looks pretty good for his or any age. Doubt he would do it, but the old team would come together quickly.”