Critical Condition

When his mother needed urgent medical care on Election Day 2020, Thomas Fisher told her one option was the emergency room at the University of Chicago Medical Center, near her South Side home. He wouldn’t be there that day, but his colleagues would.

The visit didn’t go well—despite Fisher’s calls and texts to monitor her progress and his ties to the ER, where he has been a physician for nearly two decades.

As Fisher relates in The Emergency: A Year of Healing and Heartbreak in a Chicago ER (One World), his mother left the hospital misdiagnosed, untreated, and still in pain. “She waited,” he writes, “until she couldn’t wait anymore and then got up and left,” a victim of the “blocked beds and throttled access to specialists [that] force patients into unending waits.”

“What happened to her is not an outlier,” he explains in an interview. “In that one moment, she just got caught in the bureaucracy.” Her calm demeanor didn’t help. “She wasn’t screaming in pain. She was neither presenting herself as a VIP, nor was she psychotic or bleeding. She was stoically, quietly suffering, expecting people to just take care of her. But we don’t have that kind of system.”

His mother’s emergency—triggered by a life-threatening pulmonary embolism—is just one of many referenced in Fisher’s memoir, which doubles as a policy primer and cri de coeur about the fissures in U.S. healthcare. Using mostly composite characters, Fisher reconstructs in granular detail the quotidian challenges of the ER, where doctors must make “high-stakes decisions” quickly and with limited information—and then move on to the next patient. The Emergency also touches on the crisis of Covid-19, Chicago’s epidemic of gun violence, and, above all, the macro emergency of poor healthcare outcomes for those disadvantaged by race, income, or insurance status.

“If I am in any way indicting the institution,” says Fisher, “I’m indicting myself as a part of it. My goal is to cast a light on this bigger problem: The more chaotic your life is because you exist in a society that is not equal, the more likely you are to use the emergency department for your care. Many of my patients are living check to check, working as hard as I am, with none of the rewards.” Their healthcare issues are, in part, the product of “our piecemeal insurance strategies,” Fisher says. “It’s important to take a step back and say, ‘Shouldn’t we do something different, original, and more challenging? Don’t we owe each other more?’ ”

With a medical degree from the University of Chicago and a master’s in public health from Harvard, Fisher has pursued an ambitious career path that has always led back to his native South Side.

He has served in government, as a White House fellow, and in the private sector, as an insurance company executive and president of a Medicaid managed-care company. He has taught, consulted, and done community-based academic research. But except during his year in Washington, D.C., he never stopped working shifts at the University of Chicago Medical Center. “The heart of me is an ER doctor,” he says. “I’m where I want to be. I want to care for my community.”

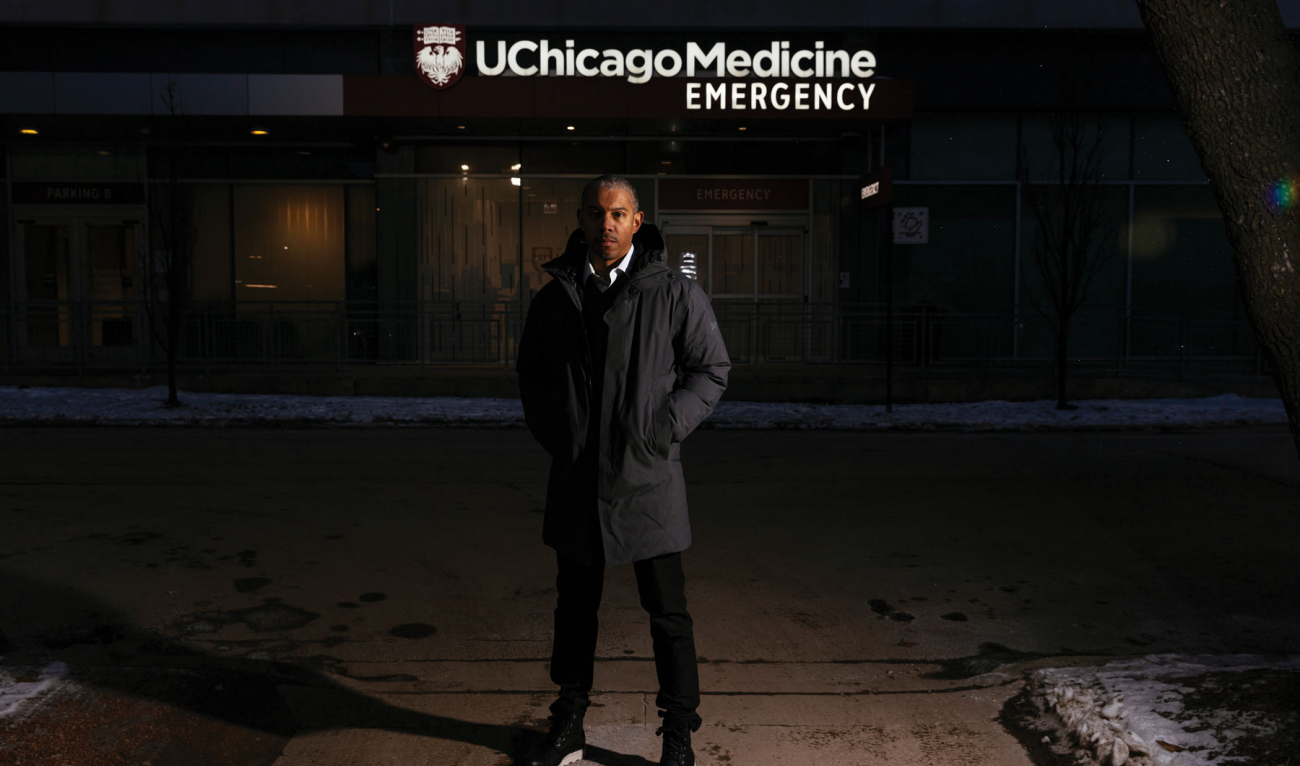

Fisher’s ER is the busiest trauma center in the state, he says, as he walks toward the entrance. “On the hot summer days when there’s violence, police cars block the street right here,” he says. TV news reporters gather on this corner to do stand-ups about the mayhem.

Inside, at a desk in the small waiting room, a sign advises: “We do not know how long your wait will be. Sorry for the wait. Thank you for your patience.” On a quiet Friday morning, the room holds just a scattering of patients. But at peak hours, for noncritical care, the wait can reach eight or nine hours—far longer on average, Fisher says, than in hospitals that serve Chicago’s wealthier, whiter, and better-insured enclaves.

Earnest, soft-spoken, and intense, Fisher, 47, retains the lean physique of a track athlete. In civilian clothing and wearing the obligatory mask, he inspires double-takes from some ER colleagues who don’t immediately recognize him. He is greeted effusively by others, including a trio of nurses.

“These are people I’ve known for decades,” says Fisher. “And we’ve seen ups and downs. We’ve gone through Covid together. We work in teams, we rely on each other, and so we understand each other’s tendencies and judgment.”

Given the procedural glitches that Fisher describes in his book, the ER’s appearance comes as a surprise. Opened in December 2017, it is a modern, state-of-the-art facility. Video screens alert the staff to incoming ambulances. Negative pressure rooms house Covid patients, and separate bays are dedicated to resuscitations and nonacute care. A food pantry offers canned goods. “So much of what comes in here is not medical,” Fisher explains, “so we try to address those things, too.”

Fisher grew up less than two miles away with two sisters in the red brick townhouse where his parents still live. His Hyde Park neighborhood, anchored by the University of Chicago (and longtime home of the Obamas), remains socioeconomically, racially, and religiously diverse—a mix of residential and commercial development, high rise and low, with a Whole Foods jostling up against a thrift store and a barbershop. Lake Michigan and its beaches form the neighborhood’s eastern boundary. After a mild fall, the trees still sport brilliant golds and reds, but on this mid-November morning, the oncoming winter’s chill and wind already are making their presence felt.

Fisher’s father is a doctor, his mother a retired social worker. In an era of segregation, Fisher’s maternal grandfather served in a Black World War II Army regiment but was sufficiently fair-skinned to attend a law school that might otherwise have barred him.

For elementary and middle grades, Fisher’s parents sent him to the private University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, whose alumni of note include Emmy Award-winning comedian W. Kamau Bell and former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. By high school, Fisher says, he wanted “an opportunity to expand my world, to no longer be in a smaller, cloistered community, to have more Black folks around me.”

He enrolled in Kenwood Academy, a well-regarded public school with a sprawling, block-long campus a short walk from home. There he excelled academically, played saxophone, and ran track. There, too, he lost an older track buddy, Larry, to the gun violence plaguing the area. “That was the peak of Chicago murders,” Fisher says. He writes of his friend: “He was real one day but just stories and memories the next. The school shrugged.”

One of Kenwood’s alums was Gary Lorain Love ’76, whose many contributions to Dartmouth included creating an admissions pipeline for gifted Black students. On a campus visit, Fisher thought Dartmouth looked like a college should. “You go up in the fall, and the mountains are aflame with color change, the air is crisp, and there’s fireplaces crackling,” he says. But its social reality turned out to be more complicated. “It felt as segregated as Chicago,” Fisher says.

The College’s community of color was small in the 1990s, and its members often forged strong bonds. Nada Maria (Payne) Llewellyn ’96, chief diversity and inclusion officer at the New York City law firm Kramer Levin, was struck by Fisher’s kindness freshman year and has been close to him ever since. She calls him “a brother by choice.” At Dartmouth, where Black students often felt both “hyper-visible and invisible,” she says, “we navigated together understanding how oppression works—and how we can maintain our own self-worth even in situations and environments that don’t value us.”

Joseph J. Ybarra ’96, a Los Angeles-based attorney and another close friend, recalls of Fisher: “He came in with a plan and knew what it was and executed it. So, from the day I met him he was premed. He knew what classes to take in what order. It was oddly like he had the game figured out. I certainly did not.”

Fisher’s best friends at Dartmouth were “either African American or Latino,” Ybarra recalls. “But Tom could move in mainstream Dartmouth circles in a way that I at least didn’t feel comfortable doing.”

“What I committed to was, if I’m going to be here, I’m doing it all,” Fisher says. “I’m going to own this whole place.” A biology major, he pursued language study in France and an exchange program to Morehouse College, the historically Black men’s college in Atlanta. On campus, he served on the dean of the College student advisory board and as an undergraduate advisor. But he almost failed to graduate after he dropped a course that left him shy of the necessary credits. (He later took an extra course in summer school.) “Sometimes I quit trying in the middle of things,” he writes of that slip-up. It was a tendency he vowed to correct.

Fisher says he was attracted to the “hands-on component” and “team aspect” of emergency medicine. “When something happens on an airplane,” he says, “they don’t want the pathologist. Knowing how to do stuff just feels good, like knowing how to build a chair or paint a house.”

To marry individual and societal perspectives on health, he interrupted his medical school education to earn a degree in public health. After his residency, he was a Robert Wood Johnson clinical scholar, a program then devoted to training physicians to be healthcare leaders. Fisher says he left thinking, “Things are obvious: All you have to do is align incentives and deliver culturally competent, patient-centered care. And I got nowhere because the challenge is much bigger than those things.”

The Emergency—with a foreword by Ta-Nehisi Coates, a National Book Award winner and MacArthur fellow who is also a longtime friend—proposes no clear solutions. But it details Fisher’s heartfelt attempts to grapple with the issues. The narrative alternates between a tick-tock of his ER shifts and other daily routines and unsent letters to patients whom he fears having failed. (He credits his editor, Chris Jackson, publisher and editor-in-chief of One World, a Random House imprint, for the literary device.)

“What I really wanted to do is recognize the real, intimate relationships that happen in a care setting, where not only is my patient a person—I’m a person,” Fisher says. “And I don’t always know the right answers.” In the letters he delves into his own background and describes the fractured state of U.S. healthcare in what he calls “a large-picture, informal, conversational way.”

One letter is different. Addressed to a colleague, another composite figure, it details a period of turmoil when the University of Chicago Medical Center took steps to reshape its admissions procedures, with potentially devastating impact on the surrounding community. In one notorious instance, in 2009, a 12-year-old who had been mauled by a pit bull was treated in the ER but not admitted for surgery. (According to news accounts, the boy had Medicaid coverage, which offers lower reimbursements than private insurance.)

Later that year, the hospital administration floated a proposal to give “patients of distinction”—those needing specialty care and with the means to pay for it—preferential access to hospital beds. “The crowding for the remaining 80 percent of patients would grow sharply,” Fisher writes, “and so would their suffering.” To him, this was a morally reprehensible result, a return to de facto segregation. After months of dodging questions, leaked plans in the media, and opposition by Fisher and some of his colleagues, hospital administrators retreated. Instead, at the suggestion of Fisher and others, the hospital reorganized its ER’s physical space to streamline care. But having seen the institution “willing to destroy bodies as inputs to its profit function,” Fisher, appalled, knew that changing the system would require him to pursue a different path.

His timing was good. In August 2010, he became a White House fellow, serving as a special assistant to U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius just after the Affordable Care Act (ACA) became law. He worked on developing ACA regulations, as well as addressing healthcare inequities. Sebelius, whose leadership qualities he praises, remains a mentor.

ACA expertise was in demand. It led Fisher to a nearly four-year stint, beginning in October 2011, as vice president for healthcare transformation for the Chicago-based Health Care Service Corp., an insurance company that needed help navigating the regulations he had helped fashion. In that corporate setting, he writes, “I slowly gained aptitude, getting humbled along the way.”

In February 2016, Fisher left for the chance to run his own show, as the first president of a Medicaid managed-care startup, NextLevel Health. “It wasn’t long,” he writes, “before ideals collided with money.” Unreliable cash flow led to the company’s decision to lay off patient navigators, who helped Medicaid recipients understand and use the system. Fisher had misgivings about the choice, but nevertheless found himself “in the suit, in that same trap” as those he had criticized in the past. “In the process,” he writes, “I learned there are no heroes.”

Encouraged by his writer friends—including Coates, New Yorker staff writer Jelani Cobb, and Atlantic staff writer Adam Serwer—Fisher decided to write a book to “take stock.” He started sketching out chapters between ER shifts, working in a café near his West Loop condo until the March 2020 lockdown shuttered restaurants.

Ironically, the coronavirus—because it slowed the flow of other patients to the ER—temporarily made care more efficient. And Fisher says the medical center, never short of personal protective equipment and never slammed to the extent of hospitals in New York, has navigated the pandemic relatively well. Still, it was “terrifying,” he says of those pre-vaccine days. “I saw a lot of colleagues get sick.”

Fisher stayed healthy. As hedges against isolation, he took walks with his younger sister and niece and tried to maintain a long-distance romance that had blossomed before the pandemic. But his girlfriend lived in Toronto, and the closed U.S.-Canada border made visits impossible. “Covid destroyed that relationship,” he says. “Zoom only goes so far.”

Fisher says he remains hopeful that the U.S. healthcare system can be repaired. What is needed, he says, is “a different level of commitment, the recognition that, while these are convoluted and complex systems, we built them, which means we can build new ones.”

Even if “we need fundamental transformation that we can’t see right now, that doesn’t absolve us from doing things today,” he says. “Oftentimes, one of the biggest critiques of healthcare is, ‘You’re just treating the symptoms—cure it.’ I’m an ER doctor. I can’t solve Covid. I can’t solve gun violence on the South Side. But that doesn’t absolve me from trying to stop the bleeding with this patient today.”

Julia M. Klein profiled Jean Hanff Korelitz ’83 in the May/June 2021 issue of DAM.