FRIDAY, MARCH 5, 1954 — DAWN

Rock Creek Park, Washington, DC

He snapped out of the blackness with a mouth full of mud.

Charlie Marder coughed up grime and spat silt, then raised himself on his elbows and tried to make sense of where he was.

Sprawled on the leafy banks of a creek, he wore a tuxedo that was insufficient to combat the March chill. A wispy fog hovered; sporadic chirping came from nearby families of wrens rising with the sun.

A stone bridge and paved road lay in front of him. Wincing with the effort, he hoisted himself onto his knees and turned. Behind him, a semi-submerged Studebaker sat in the creek’s muddy bank, its driver’s door open.

He squinted and could just make out, downstream, the recently restored old Peirce Mill and its waterwheel. He was in Rock Creek Park, 1,754 acres of woods, trails, and road tucked in Northwest Washington, DC, far from his Georgetown brownstone.

How did I get here?

Charlie said it to himself, first in his head and then as a whisper and then repeating it aloud: “How did I get here?” His voice was gravelly. He stumbled as he tried to stand, and realized that he was drunk. His mouth was parched. Where had he been drinking?

He looked at his Timex, adjusting his wrist to catch the light: 4:55 a.m. Memories began to emerge—a party, a celebration, a club of some sort. Frank Carlin, the powerful House Appropriations Committee chairman, encouraging a young, attractive waitress to do something. What was it? She poured ice water onto a sugar cube held on a flattened perforated spoon over a glass. And the glass contained absinthe. “This is how the French do it,” Carlin said. And from there the night went dark.

Charlie staggered forward. Looked back at the Studebaker. Muddy tracks traced the car’s path from the road to its final resting place on the riverbank. Okay. I skidded off the parkway. This was a problem. But nothing insurmountable. An accident. Maybe he could just walk away. He didn’t recognize the car, had no recollection of being behind the wheel. “Absinthe,” he muttered under his breath.

He took stock of the situation. This was not even a ripple in the ocean of atrocities he’d witnessed in France during the war. He was not a person of poor character. He was someone who tried to do good; he was currently fighting for his fellow troops from the turret of his congressional office. In the grand scheme of things, would it be so wrong to just leave the scene and spare himself a litany of questions he might not be able to answer?

And then he heard it: a low din, a car’s motor heading toward him. Ah, well, Charlie thought. Fate is making the decision for me. I’ll stand here and face whatever happens. He exhaled, steeling himself.

With relief, he recognized the spit-shined baby-blue Dodge Firearrow sport coupe. It belonged to someone he knew, a friend, even: well-connected lobbyist Davis LaMontagne. It was a car perfectly suited to its owner, glossy and stylish. LaMontagne pulled the car to a stop at the side of the road and rolled down his window.

“Charlie,” he said, “Jesus Christ.”

He opened the door and emerged, looking as though he’d just stepped out of the pages of a magazine ad for cigarettes or suits. His hair slicked back, his blue hip-length bush jacket hanging loosely from his broad Rocky Marciano build, he briefly surveyed the scene, then began to negotiate his way carefully down the rocky, muddy decline toward Charlie.

“Davis,” Charlie said. “I have no idea—” He spread his arms to finish the sentence for him.

Before LaMontagne could respond, they heard a sound in the distance.

Another car.

Its windows must have been open despite the morning chill; as it drew closer, they could hear the bark of a radio newscaster. LaMontagne didn’t move, as if he were freezing the action in his world until this problem took care of itself.

And it did. The sounds of car and radio changed pitch, suggesting the car, off in the distance, was now driving away from them.

Unruffled, LaMontagne continued his approach and arrived at Charlie’s side. Charlie was hit with a whiff of his smoky, woody cologne.

“Are you all right?”

“Fine,” Charlie said, though his head was throbbing and he would have given his left arm for a glass of water. “Do you have any idea how I got here?”

“Last I saw you was at the party,” LaMontagne said. “You were snockered. Then you made an Irish exit.” He raised his hand and made an elegant illustrative explosion with his fingertips: poof.

“You okay? Jesus. Thank God you’re alive.” LaMontagne looked over his shoulder at the Studebaker. “Whose car is that?”

Charlie suppressed a wave of nausea; when it passed, he rubbed his chin and shrugged. “I have no idea.”

LaMontagne pulled on his black leather gloves, took a folded handkerchief from his suit pocket, and leaned into the driver’s seat of the Studebaker. He wiped the steering wheel, the gearshift, the radio knobs, and the window roller; on his way out, he removed the keys from the ignition, then wiped the door handle. Sliding the keys into his pocket, he stood up straight and put a hand on Charlie’s shoulder.

“Let’s burn rubber,” he said.

Charlie let himself be guided briskly up to the road and the Dodge, where he collapsed with relief in the passenger seat as LaMontagne shut the door firmly.

Halfway around the front of the car, the man suddenly stopped. Through the windshield, Charlie saw him looking down at the narrow shoulder of the road.

“Charlie,” LaMontagne said, a seriousness in his baritone Charlie had never heard before. “You need to see this.”

Charlie exited and joined LaMontagne, who was staring at what at first appeared to be a bundle of discarded clothes in a narrow drainage ditch but upon closer examination proved to be a young woman lying on her right side, facing away from the road, her left arm twisted awkwardly behind her. Blood had soaked through the back of her low-cut dress.

Charlie’s heart thudding into his lungs, he slowly knelt on the grass and gently rolled the woman toward him; she fell onto her back. She had red hair and couldn’t have been more than twenty-two. Charlie had vague memories of her from the night before. Is she a cocktail waitress, maybe?

He looked up at LaMontagne in disbelief, but the man’s gaze was elsewhere, back toward the spot where he’d found Charlie. “I didn’t think anything of it before, but the passenger side door of that Studebaker is open. Jesus. Do you think she fell out of your car?”

Fighting his rising anxiety, Charlie gingerly placed two fingers on the side of the woman’s neck. She was porcelain pale and still. Her eyes were closed, sealed by thick fake lashes. Her body was cool to the touch. He could feel no pulse.

He looked at LaMontagne and shook his head slowly.

“Christ,” said LaMontagne. He squatted and put two fingers on the woman’s neck to see for himself. Then on her wrist. He hung his head briefly, then seemed to collect himself. He stood, moved behind the young woman’s lifeless body, bent down, and threaded his arms beneath her shoulders.

Charlie was numb, motionless.

LaMontagne looked at him with gravity and impatience.

“Congressman,” he said sharply. “Grab her feet.”

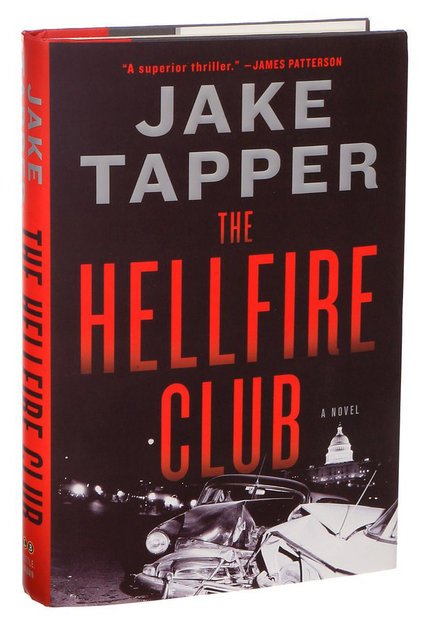

Excerpted from The Hellfire Club by Jake Tapper. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company.