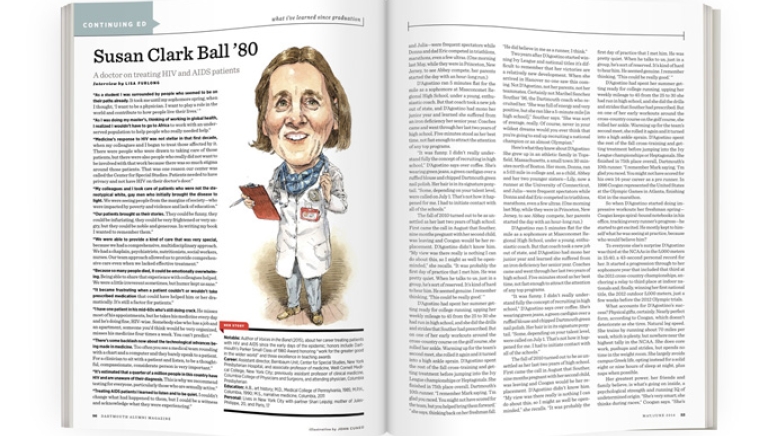

Notable: Author of Voices in the Band (2015), about her career treating patients with HIV and AIDS since the early days of the epidemic; honors include Dartmouth’s Parker Small Class of 1980 Award honoring “work for the greater good in the wider world” and three excellence in teaching awards

Career: Assistant director, Bernbaum Unit, Center for Special Studies, New York Presbyterian Hospital, and associate professor of medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City; previously assistant professor of clinical medicine, Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, and attending physician, Columbia Presbyterian

Education: A.B., art history; M.D., Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1985; M.P.H., Columbia, 1990; M.S., narrative medicine, Columbia, 2011

Personal: Lives in New York City with partner Shari Leipzig; mother of Jules-Philippe, 20, and Paris, 17

“As a student I was surrounded by people who seemed to be on their paths already. It took me until my sophomore spring, when I thought, ‘I want to be a physician. I want to play a role in the world and contribute to how people live their lives.’ ”

“As I was doing my master’s, thinking of working in global health, I realized I wouldn’t have to go to Africa to work with an underserved population to help people who really needed help.”

“Medicine’s response to HIV was not stellar in that first decade, when my colleagues and I began to treat those affected by it. There were people who were drawn to taking care of those patients, but there were also people who really did not want to be involved with that work because there was so much stigma around those patients. That was one reason our center was called the Center for Special Studies. Patients needed to have privacy and not have HIV on their doctor’s door.”

“My colleagues and I took care of patients who were not the stereotypical white, gay men who initially brought the disease to light. We were seeing people from the margins of society—who were impacted by poverty and violence and lack of education.”

“Our patients brought us their stories. They could be funny, they could be infuriating, they could be very frightened or very angry, but they could be noble and generous. In writing my book I wanted to remember them.”

“We were able to provide a kind of care that was very special, because we had a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach. We had a chaplain, psychiatrists, nutritionists, social workers, nurses. Our team approach allowed us to provide comprehensive care even when we lacked effective treatment.”

“Because so many people died, it could be emotionally overwhelming. Being able to share that experience with colleagues helped. We were a little irreverent sometimes, but humor kept us sane.”

“It became frustrating when a patient couldn’t or wouldn’t take prescribed medication that could have helped him or her dramatically. It’s still a factor for patients.”

“I have one patient in his mid-60s who’s still doing crack. He misses most of his appointments, but he takes his medicine every day and he’s doing fine, HIV-wise. Somebody else who has a job and an apartment, someone you’d think would be very organized, misses his medicine four times a week. You can’t predict.”

“There’s some backlash now about the technological advances being made in medicine. Too often you see a medical team rounding with a chart and a computer and they barely speak to a patient. For a clinician to sit with a patient and listen, to be a thoughtful, compassionate, considerate person is very important.”

“It’s estimated that a quarter of a million people in this country have HIV and are unaware of their diagnosis. This is why we recommend testing for everyone, particularly those who are sexually active.”

“Treating AIDS patients I learned to listen and to be quiet. I couldn’t change what had happened to them, but I could be a witness and acknowledge what they were experiencing.”