Superfine and Dandy

Monica Miller never dreamed that her 2009 book, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, would one day inspire an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. The exhibition, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, was celebrated at May’s star-studded Met Gala, one of the fashion world’s biggest nights. Each year at the fundraising extravaganza, hundreds of A-list celebrities and other partygoers go all-out to dress in styles that evoke the exhibition’s theme.

“The book was a revision of my Ph.D. dissertation and is really literary and culturally focused,” says Miller, a professor and chair of the Africana studies department at Barnard College. “I had no idea that it would have any play in fashion studies.”

Fast-forward to September 2023, when Andrew Bolton, the Costume Institute’s curator in charge, asked Miller if she would serve as guest curator for this year’s exhibition on Black dandyism. “While the theme certainly resonates with the current political landscape, it was originally conceived by the renewed interest in men’s fashion,” Bolton said during the exhibition’s press preview.

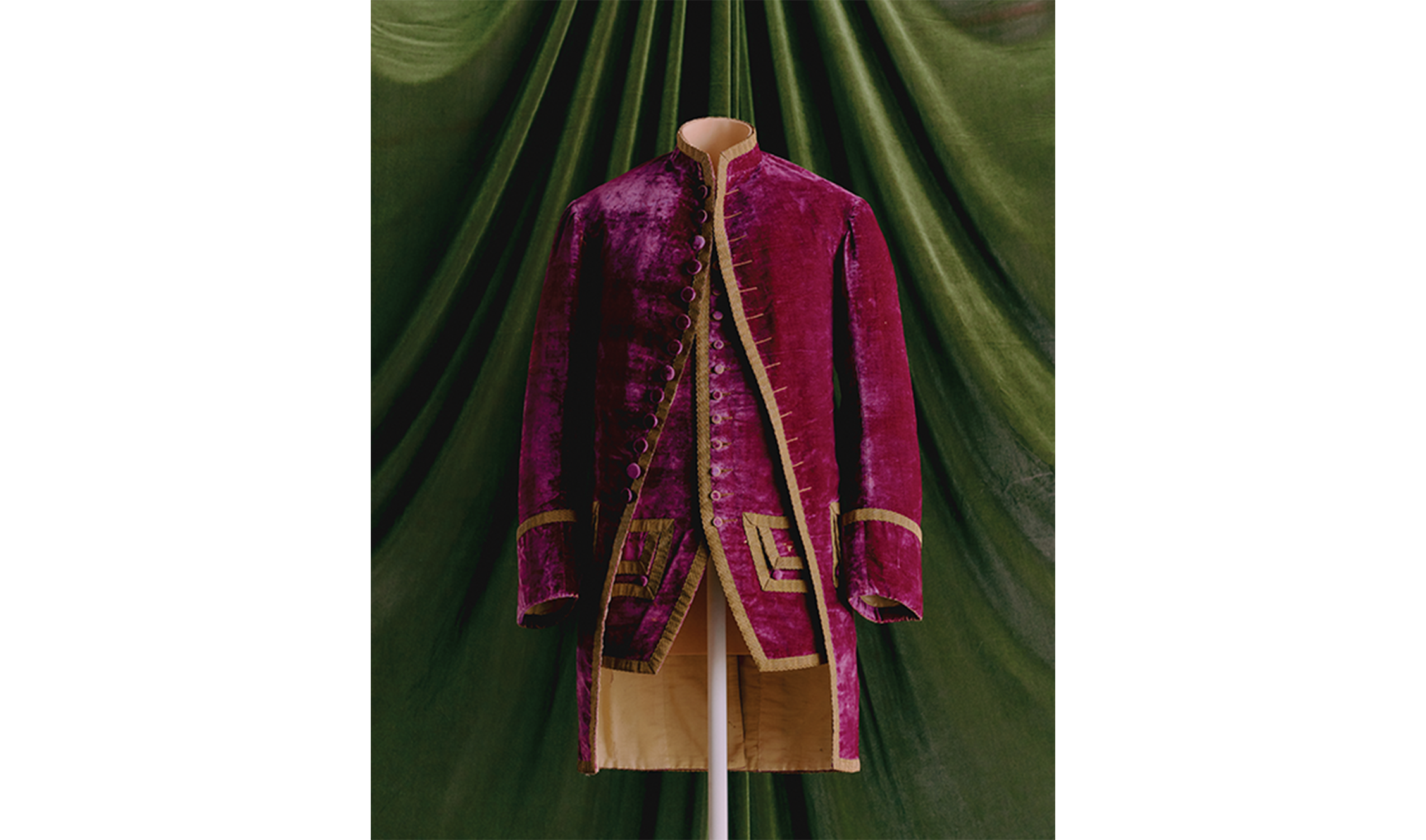

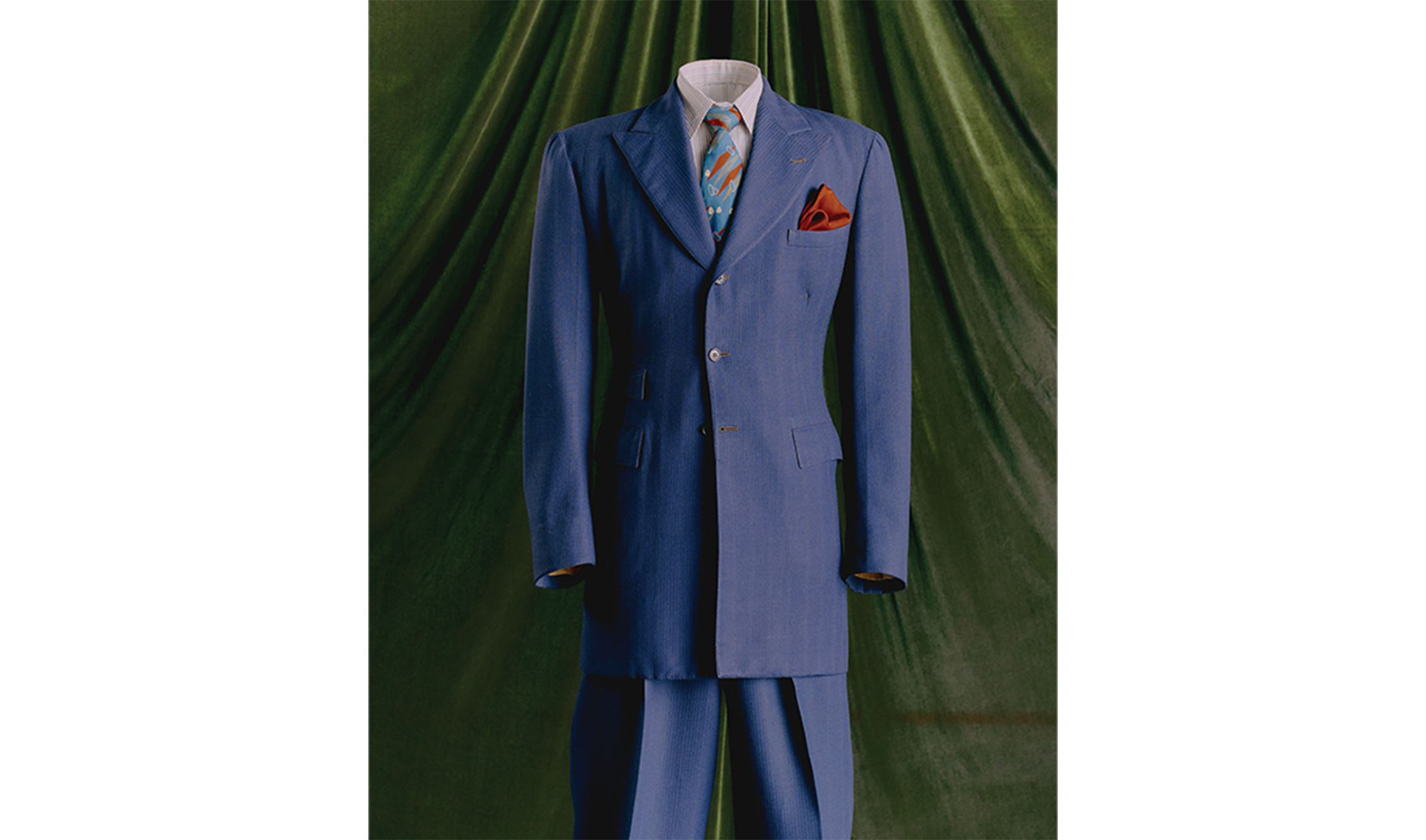

Dandyism emerged during the 18th century, a period when Europe’s upper classes flaunted their wealth by dressing their servants in over-the-top garments that reflected then-current fashion trends. Through time, free and enslaved Black people began to embrace dandyism as a way to shape and express their identities through clothes and accessories. It continued to influence Black fashion throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. The late André Leon-Tally, a former editor-at-large of Vogue, embodied modern-day dandyism with his signature capes and sharp tailoring. Bolton had Leon-Tally in mind when he picked up Miller’s book and made the call.

“It was just completely out of the blue and flabbergasting but also fantastic,” Miller says of that conversation. She knew that fashion studies scholars and Black designers had been interested in her work, but to be recognized by the Met stunned her. “This was the highest honor.”

Superfine, which runs through October 26, reflects 300 years of Black style influenced by African and European fashion trends. The exhibition is divided into 12 sections that Miller and her team felt represented Black dandyism, inspired in part by Zora Neale Hurston’s 1934 essay, “Characteristics of Negro Expression.”

“This [exhibition] has been, I think, particularly meaningful and emotional and has a real heightened sense of purpose because of the times that we’re living in,” Anna Wintour, then Vogue’s editor-in-chief, told Good Morning America.

Although her biggest stage yet, this wasn’t Miller’s first foray into the museum world. As a Dartmouth undergrad the classical studies and English major studied in London, where she spent much of her time visiting museums and libraries. “London was one of the first big cities I was living in that had cultural institutions I could just get in and explore,” Miller recalls. The experience sharpened her interest in public history.

The opportunity to be the first Black woman to curate a Costume Institute exhibition was “a privilege and a responsibility,” Miller says. She was excited to translate her research from text to a visual, garment-based exhibition accessible to the public.

Developing the exhibition took Miller, Bolton, two other curators, and a research assistant a year and a half, during which time Miller continued to teach. Because the Costume Institute introduces a new exhibition each year, the timeline for the design was faster than for most museum exhibitions. Having her book as a blueprint proved useful.

“We had a real narrative to start with,” Miller says. “We weren’t starting from scratch.”

The exhibition highlights hundreds of years of garments created by Black fashion designers representing all eras of African American sartorial history, from slavery to the present, including contributions from well-known contemporary creators such as the late Virgil Abloh, photographer Tyler Mitchell, and Olivier Rousteing, creative director for Balmain, as well as lesser-known designers.

Tracking down historical garments, some of which date to the 17th and 18th centuries, was particularly challenging. The team worked with historical societies and regional museums around the world, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Historic New Orleans Collection, the Chicago History Museum, and the Frederick Douglass Museum. Because many of the oldest garments were worn or made by enslaved people, very few samples were considered worthy of preservation by early collectors and antiquarians. This left Miller and her team with significant obstacles in finding materials for the exhibition.

Miller also relied on new scholarship that has emerged since her book was published, creating a visual update of her book through a contemporary, global lens. For instance, the work of C. Riley Snorton, who writes about the history of transgenderism in African American culture, influenced the exhibition’s section on disguise, which asks visitors to contemplate how clothing can reveal or conceal identity, especially as it relates to race, gender, class, and sexuality. “That part of the exhibition owes so much to Riley’s work,” Miller says.

Another topic she hadn’t written about previously was the influence of horse racing and jockey silks on Black dandyism.

“I knew about the relationship of jockeys to Black male style, but I hadn’t had a way to talk about it before,” Miller says. One singular garment—a pristine historical jockey silk crafted by enslaved laborers in the mid-19th century—became the hallmark of a section titled “Champion.” Sourced from the Charleston Museum in South Carolina, the jacket is crafted with red silk satin and features vertical stripes of appliquéd green silk satin ribbon and white breeches. This ensemble, created for equestrian Col. William Alston of Clifton and Fairfield Plantations in South Carolina, is likely the earliest surviving American set—and would have been identical to those worn by Alston’s enslaved riders, Miller says.

“That garment is just phenomenal. It’s so incredibly well preserved. It probably wasn’t worn. We were able to create a conversation around Black dandyism in sports, which has a historical component but also a contemporary one, based on our ability to display that garment,” Miller says. The jockey silks provided the opportunity to talk about the history of Black athletes and celebrate the sartorial stylings of men such as Jack Johnson, Muhammed Ali, and Walt Frazier.

In May Miller could finally appreciate the fruits of her labor as she walked up the iconic elongated stairs at the 77th annual Met Gala alongside some of the most notable figures in fashion and Hollywood. She sported an ensemble from English menswear designer Grace Wales Bonner, as did F1 driver Lewis Hamilton, actor Jeff Goldblum, and photographer Tyler Mitchell. Miller’s was a long black dress and short-sleeve cropped cape featuring cowrie shells from Wales Bonner’s archives.

Choosing which outfits and artwork to display in the Met exhibition was one thing. But for the gala, celebrities from every walk of American culture looked to Miller’s work for inspiration. In her role as guest curator, Miller spoke with members of the Met’s host committee—composed of notable Black athletes, actors, writers, and artists such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Simone Biles, Spike Lee, and Janelle Monáe—about what she thought was important for them to know as they designed their own looks. “A fair amount of the guests did their homework,” she says. “It was fun to see how they interpreted what we talked about.”

One of those who understood the assignment was British model and actress Jodie Turner-Smith, who wore a Burberry ensemble inspired by 19th-century Black French equestrian Selika Lazevski that featured a floor-length maroon leather coat with a cinched waist and dramatic train, pants, and a coordinating exaggerated top hat—a Victorian silhouette first captured in a portrait of Lazevski from 1891.

Turner-Smith and her team “looked for something in history that was inspiring—a person who had their own sense of style and was kind of showing off when that wasn’t a thing for Black people. Someone who had that personality and chutzpah,” Miller says. “It was really great.”

Doechii, an American rapper, wore a look inspired by Julius Soubise, an 18th-century Black Londoner and one of the earliest known Black dandies. Doechii told Elle magazine that she had read Miller’s book and was struck by Soubise’s story. For the Met Gala, she wore a cropped Louis Vuitton monogrammed tuxedo jacket with tails, tailored Bermuda shorts, knee-high socks, and loafers.

“I’m a huge fan of Monica Miller. Her book is amazing,” Doechii said in an interview with Vogue.

Miller says she keeps referring to the exhibition as “my biggest classroom yet,” and that it has launched a new chapter in her teaching career, spurring her to translate classroom lessons through cultural experiences, objects, and community spaces.

Wintour said she hopes Superfine will “really put a light on the talent of all these arbiters of style—look at their traditions and their history and their culture. But most importantly to me, in a way, is when I look at the show, I see freedom. I see liberation. I see hope. I see respect. And I see joy.”

Kelly Vaughan is a Connecticut-based editor and writer.