It was a Tuesday evening, January 1986, and a deep snow was piling up in the yard at the Connecticut home of Barry Nova ’54. The phone rang. It was his classmate Dartmouth President David T. McLaughlin ’54, and his tone was urgent.

“He said, ‘Barry, I need to see you. You have to come up,’ ” Nova recalls. “He said, ‘I want you here at 9 o’clock tomorrow.’ I said, ‘It’s snowing.’ And he said, ‘We have to talk about Scott, and we have to talk about him now.’ ”

Nova grabbed a tie and jacket the next morning and skidded his way up Interstate 91. Barry’s son Scott had been lodged with 28 other students in the winding staircase of Parkhurst, blocking access to the president’s office as part of a protest against apartheid.

The occupation of Parkhurst was just the latest nonviolent demonstration organized on campus by students trying to bring attention to the College’s investments in companies doing business in South Africa. The previous fall the younger Nova had helped lead a series of sit-ins and rallies—including the construction of shanties on the Green—to express solidarity with black South Africans. When conservative students vandalized the shanties, Nova led an angry protest in response, grabbing a megaphone and yelling at one point, “You racists will be stopped!” according to an account in The Dartmouth.

When Nova’s father arrived at the president’s office that winter day in 1986, McLaughlin didn’t tread lightly. His patience with the protests was wearing thin. “He said, ‘I like Scott. I admire his concern for the human race. I admire his intelligence,’ ” the senior Nova recalls. “But I want him to know that I run the College and he does not.’ ”

Nova took his son to lunch at the Hanover Inn that day to try to persuade him to back down. Dressed in a filthy coat, unshaven, long hair disheveled, Scott sat quietly through the lunch and said nothing. A week later the call came that Scott and a group of protesters had taken over Baker Tower. Barry phoned McLaughlin and told him, “I don’t know what you’re going to do. All I can say as a friend and a father is, please don’t hurt him…badly.” As Barry remembers it, Scott was placed on something called “eternal probation.”

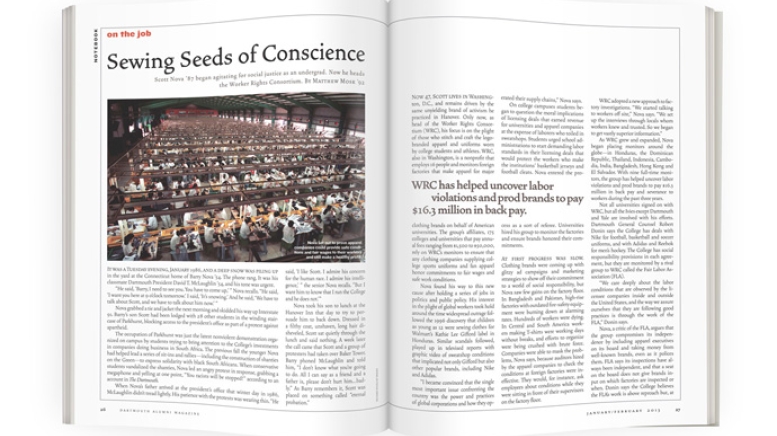

Now 47, Scott lives in Washington, D.C., and remains driven by the same unyielding brand of activism he practiced in Hanover. Only now, as head of the Worker Rights Consortium (WRC), his focus is on the plight of those who stitch and craft the logo-branded apparel and uniforms worn by college students and athletes. WRC, also in Washington, is a nonprofit that employs 16 people and monitors foreign factories that make apparel for major clothing brands on behalf of American universities. The group’s affiliates, 175 colleges and universities that pay annual fees ranging from $1,500 to $50,000, rely on WRC’s monitors to ensure that any clothing companies supplying college sports uniforms and fan apparel honor commitments to fair wages and safe work conditions.

Nova found his way to this new cause after holding a series of jobs in politics and public policy. His interest in the plight of global workers took hold around the time widespread outrage followed the 1996 discovery that children as young as 12 were sewing clothes for Walmart’s Kathie Lee Gifford label in Honduras. Similar scandals followed, played up in televised reports with graphic video of sweatshop conditions that implicated not only Gifford but also other popular brands, including Nike and Adidas.

“I became convinced that the single most important issue confronting the country was the power and practices of global corporations and how they operated their supply chains,” Nova says.

On college campuses students began to question the moral implications of licensing deals that earned revenue for universities and apparel companies at the expense of laborers who toiled in sweatshops. Students urged school administrations to start demanding labor standards in their licensing deals that would protect the workers who make the institutions’ basketball jerseys and football cleats. Nova entered the process as a sort of referee. Universities hired his group to monitor the factories and ensure brands honored their commitments.

At first progress was slow. Clothing brands were coming up with glitzy ad campaigns and marketing strategies to show off their commitment to a world of social responsibility, but Nova saw few gains on the factory floor. In Bangladesh and Pakistan, high-rise factories with outdated fire-safety equipment were burning down at alarming rates. Hundreds of workers were dying. In Central and South America workers making T-shirts were working days without breaks, and efforts to organize were being crushed with brute force. Companies were able to mask the problems, Nova says, because auditors hired by the apparel companies to check the conditions at foreign factories were ineffective. They would, for instance, ask employees about conditions while they were sitting in front of their supervisors on the factory floor.

WRC adopted a new approach to factory investigations. “We started talking to workers off site,” Nova says. “We set up the interviews through locals whom workers knew and trusted. So we began to get vastly superior information.”

As WRC grew and expanded, Nova began placing monitors around the globe—in Honduras, the Dominican Republic, Thailand, Indonesia, Cambodia, India, Bangladesh, Hong Kong and El Salvador. With nine full-time monitors, the group has helped uncover labor violations and prod brands to pay $16.3 million in back pay and severance to workers during the past three years.

Not all universities signed on with WRC, but all the Ivies except Dartmouth and Yale are involved with his efforts. Dartmouth General Counsel Robert Donin says the College has deals with Nike for football, basketball and soccer uniforms, and with Adidas and Reebok for men’s hockey. The College has social responsibility provisions in each agreement, but they are monitored by a rival group to WRC called the Fair Labor Association (FLA).

“We care deeply about the labor conditions that are observed by the licensee companies inside and outside the United States, and the way we assure ourselves that they are following good practices is through the work of the FLA,” Donin says.

Nova, a critic of the FLA, argues that the group compromises its independence by including apparel executives on its board and taking money from well-known brands, even as it polices them. FLA says its inspections have always been independent, and that a seat on the board does not give brands input on which factories are inspected or when. Donin says the College believes the FLA’s work is above reproach but, at the prodding of a group of current students acting independently of Nova, it is considering joining WRC as well.

As more universities signed on with Nova’s group, he began setting his sights on a bigger goal—proving that apparel companies could provide safe conditions and fair wages to their workers and still make a healthy profit.

When WRC flagged a factory in the Philippines for serious labor violations, the CEO of the company that was making collegiate clothing there had a different reaction from most: He wanted to institute changes. The executive from Knights Apparel, a South Carolina clothing company that has licensing deals with the NCAA and dozens of universities for T-shirts, sweatshirts and other garments, began talking with Nova about measures that could help WRC achieve its goals. He proposed a pilot program. Nova liked the idea and in 2008 suggested they try to build a model workplace in the Dominican Republic town of Altagracia, where he had already spent years helping workers fight severe labor rights abuses. In Altagracia typical workers made 90 cents an hour. That was high for the apparel industry—in Bangladesh workers make 18 to 20 cents an hour—but not enough to support a family.

“[Knights Apparel] agreed to work with us to open a factory that would be the first one we know of that pays workers a living wage and welcomed and accepted unionization,” Nova says.

The factory has been open two years, paying workers roughly $3 an hour. Knights Apparel says the extra costs are not passed on to customers. Instead, the company agreed to accept a smaller profit margin. Nova says the damage to the company’s bottom line has been modest: It still profits off the clothes made in Altagracia. “It is what we’d like to see in every factory we walk into,” Nova says, “not just because the wages are higher but because the nature of the workplace is different. There is a level of respect between management and workers. Absent is the intense pressure and fear that we see in every other factory.”

The success in Altagracia is almost invisible in the shadow of a massive global apparel industry, but Nova believes it is more than symbolic. “We know that the economics of global supply chains [where labor costs are a tiny fraction of retail prices] make it possible for workers to be paid vastly higher wages, thereby transforming the lives of workers and whole communities, with little or no cost impact for consumers,” he says. “The Altagracia project shows what is achievable. The problem is not technical or economic, but political and moral: Brands and retailers do not want to abandon a business model that has proven lucrative, even though it is a disaster for workers. Our job is to convince them to do so.”

When Nova stepped onto the stage to receive his diploma from Dartmouth he refused to shake President McLaughlin’s hand—perhaps his final protest in Hanover. It would be two more years before the College, under President James O. Freedman, would finally sell off the $11.5 million in investments it held in companies doing business in South Africa.

Barry Nova believes that decision to divest left a deep impression on his son: Major social change, even something as daunting as higher wages and better working conditions in distant lands, should never be written off as impossible.

“As much as it might seem at a certain moment that change is extremely far away and that the corporations are in an incredibly strong position,” Scott says with a smile, “things can change quickly.”

That’s true even at Dartmouth. Recently Nova went online and purchased a College sweatshirt. It was made by Knights Apparel at the factory in Altagracia.

Matthew Mosk is a reporter for ABC News and a frequent contributor to DAM. He lives in Annapolis, Maryland.