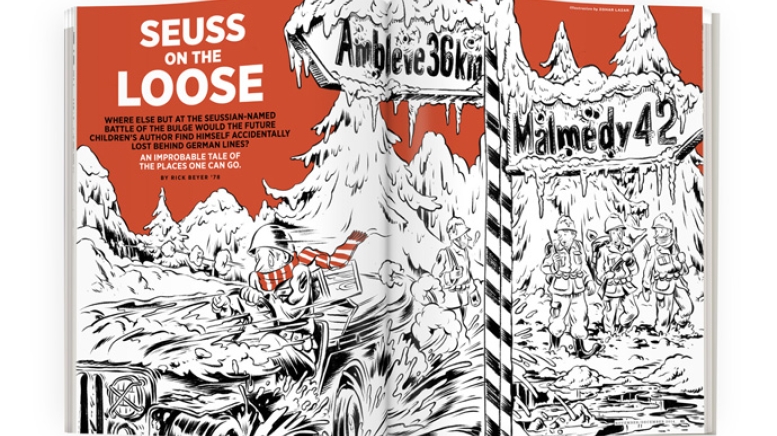

The Germans were coming. Waves and waves of them, in a desperate last-ditch attempt to reverse the tide of battle and win World War II. More than 200,000 strong, armed to the teeth with Panzer tanks, Nebelwerfer rockets and 88-mm artillery pieces, they burst through American lines in Luxembourg and Belgium, jagged red arrows jutting west on the map, sending U.S. Army units fleeing in disarray. It was December 16, 1944, the first day of what would become one of the most famous battles of the war: the Battle of the Bulge.

Directly in the path of this fearsome Nazi juggernaut, and more than a little surprised to discover that it was headed right for him, was a 40-year-old cartoonist and writer already known to his fans by the pen name that would one day be world famous: Dr. Seuss.

Maj. Ted Geisel ’25 was a strictly rear-echelon officer working on training films for the military. How he happened to find himself in the dangerous position of being threatened by three German Panzer armies is a story with a colorful cast of characters that includes a controversial publisher, a Dartmouth sociology professor, Hollywood director Frank Capra, actress Marlene Dietrich and a top-secret Army deception unit. It is a tale so strange it is a wonder the good doctor didn’t write it himself.

Geisel adopted his famous Seuss moniker while writing for the Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern. In the ensuing years he wrote and drew advertisements for such companies as Standard Oil and Flit Bug Spray. He also had some modest success as a children’s author, starting with And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street in 1937. Early in 1941 he branched off into a new line of work as a political cartoonist, drawing hundreds of cartoons for the liberal New York newspaper PM.

Geisel continued his political cartooning after the United States entered the war in December 1941 but soon came to feel he should be doing more for the war effort. In 1943 he enlisted in the Army and wangled his way into a special documentary unit headed by celebrated director Capra. It was a strictly Hollywood outfit—their offices on the Twentieth Century Fox lot became known as “Fort Fox.” Among Geisel’s creative co-workers were composer Meredith Willson, who later wrote The Music Man, and novelist Irving Wallace. Col. Capra taught Maj. Geisel the basics of filmmaking, and Geisel became involved in numerous projects. He wrote many scripts for Private Snafu instructional cartoons, directed by legendary Warner Brothers animator Chuck Jones and voiced by Mel Blanc, the voice of Daffy Duck.

In the fall of 1944 Geisel finished work on a live action film titled Your Job In Germany, intended to instruct GIs occupying Germany how to handle themselves there. It was decided he should fly to Europe to obtain approvals for the film from the generals leading the troops. [You can view a clip from the film here.]

Geisel arrived in Paris in November 1944 and spent the next few weeks zigzagging across American-occupied Europe, visiting one headquarters after another to show the film to various generals. He said later that he managed to play it for every high-ranking general in the theater except for one: Gen. George Patton. “Somebody else took the film and played it for Patton,” Geisel recalled to his biographers, Judith and Neil Morgan. “I was told he said ‘Bullshit!’ and walked out of the room.”

There was also plenty of time for relaxation on this wartime junket. On a visit to Luxembourg, Geisel attended a Marlene Dietrich concert, watching as the famous star sang some of her hit songs and even played the musical saw. He noted in his diary that he celebrated Thanksgiving in Aachen, Germany, recently taken by the Allies, with a meal of “Wiener schnitzel, wursts and wassail.”

In civilian life Maj. Ralph Ingersoll was a controversial celebrity journalist. The New York Times once called him “a prodigiously energetic egotist.” Although Geisel’s star would rise sharply in the decades after the war, in 1944 Ingersoll was the far more famous of the two. He had been managing editor of The New Yorker and Fortune before he started the innovative PM. There he had launched Geisel’s career as a political cartoonist. Now Ingersoll was serving as an officer in the special plans branch of Gen. Omar Bradley’s 12th U.S. Army Group.

Geisel never offered a detailed explanation of what went on during those three days or exactly where he went. Although it is sheer speculation, the reason may be that he was trying to keep a secret that he never should have been told.

Geisel had already run into Ingersoll on his travels across Europe, and on December 13, 1944, he strolled into Ingersoll’s Luxembourg office for a chat. Another officer present was Capt. Wentworth Eldredge ’31. Before the war Eldredge was a sociology professor at Dartmouth, and he would return to the College to become chairman of the department, retiring in 1974. Ingersoll and Eldredge were both deception planners, tasked with crafting battlefield illusions to fool the Germans about the size and location of American forces. “Geisel wanted to go up to the front to see what was what,” according to Eldredge’s account of the meeting. In Eldredge’s words, Geisel wanted to go on a “swanning tour” of a safe area.

On that particular day, Ingersoll was as informed as anyone in the U.S. Army about what would constitute a “safe” part of the front. Gen. Bradley’s intelligence officers had drafted him to write the latest “Enemy’s Capabilities” report, with the hope that his vivid journalistic prose would get through to the general better than the mind-dulling militarese usually employed. Armed with this information, Ingersoll unrolled a map on the desk and consulted with Eldredge. “Ralph and I talked it over,” said Eldredge, “and concluded that the ‘safest’ place would be the 106th Division front—a very calm sector.” Ingersoll assured Geisel that it was the perfect spot. “There won’t be much action because we’ve just done an intelligence sweep of the area.”

A few days later, on a misty Saturday morning, December 16, Geisel and his driver set off in a jeep north from Luxembourg City. Unfortunately for them, Ingersoll and Eldredge were stunningly misinformed—as was the rest of the U.S. Army. Unknown to anyone, the Germans had spent months preparing for a massive counterattack against the Americans. The Nazi operation Autumn Mist was unleashed at almost the same instant Geisel’s jeep left Luxembourg City. And his route would take him right across the enemy’s intended path. It was as if he were crossing in front of a Class Five hurricane with no knowledge that the storm was even bearing down on him.

Precisely what happened to Geisel during the next three days, as the German attack spread across Luxembourg and Belgium, remains somewhat of a mystery. Maj. Geisel’s crisply typed “Overseas Itinerary,” submitted upon his return, offers little information. It baldly states that he drove from Luxembourg to Aachen, Germany, on December 16; from Aachen to Verviers, Belgium, on December 17; and from Verviers to the safety of Brussels on December 18.

More can be gleaned from a battered Michelin road map that Geisel carried through his trek across war-torn Europe. It appears to trace a route north through soon-to-be-surrounded Bastogne and up to Aachen as outlined in the itinerary. But there is one major discrepancy: a side trip toward the front, right toward the “quiet spot” where the 106th Division was holding the line east of the Belgian town of St. Vith. The crudely crayoned line on the map ends in a loop just a few miles from a small Belgian town called Malmedy that would soon be emblazoned in screaming headlines.

The fragmentary descriptions of the expedition that Geisel offered through the years suggest much more of an adventure than either the map or the official records. Reconnoitering toward where it believed the front was, Geisel’s traveling party suddenly found itself cut off from American forces. At first it didn’t seem like a big problem. “I thought the fact that we didn’t seem to be able to find any friendly troops in any direction was just one of the normal occurrences of combat,” he told a New Yorker reporter. Then, in the middle of a downpour, he said an MP going in the opposite direction told him he was 10 miles behind enemy lines. “Day of semi-exhaustion semi-battle fatigue,” he wrote in his journal. He told his biographers that he was trapped for three days behind German lines and rescued by a British unit. “The retreat we beat,” he added, in words with a Seussian ring, “was accomplished with a speed that will never be beaten.”

How close a call did Geisel have? German paratroopers were roaming the area in which he was traveling. Eight thousand men from the American 106th Division, holding the “safe” part of the front Geisel planned to visit, were forced to surrender en masse to the Germans. (Among them was a young writer named Kurt Vonnegut, whose experiences as a prisoner of war during the firebombing of Dresden formed the basis for his novel Slaughterhouse-Five.) In the town of Malmedy, just a few miles away from the loop marked on Geisel’s map, 84 American prisoners were executed by the SS, an event that became known as the Malmedy massacre.

Geisel never offered a detailed explanation of what went on during those three days or exactly where he went. Although it is sheer speculation, the reason may be that he was trying to keep a secret that he never should have been told. Geisel’s former boss, Ralph Ingersoll, was involved in planning the operations of a top-secret deception unit, the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, also known as the Ghost Army. The unit used inflatable tanks, sound effects and dramatic flair to deceive the Germans on the battlefield. Its existence was known only to a few. Geisel’s journal shows that while in Luxembourg he met not only with Ingersoll and Eldredge, but also with their boss, Col. Billy Harris. Is it possible that they decided to give the visiting VIP author and illustrator a chance to visit the Ghosts?

On Geisel’s map there is a lone arrow that points from Luxembourg to the exact spot where the Ghost Army was impersonating the 75th Division. The unit contained many artists, some of whom may well have been friends with Geisel. The Dietrich concert Geisel attended in November just happened to be in the same building where the Ghost Army was billeted. The evidence is circumstantial, but it may be that Geisel was let in on the secret, and that’s part of what led to him wandering around in danger of being captured or killed by the German onslaught. A breach of security such as that would be difficult to explain. Good reason, perhaps, to remain somewhat tight-lipped about it in later years.

By December 20, 1944, as the battle raged on, Geisel was safely back in Paris. But Ingersoll and Harris hadn’t heard any word from him and were exceedingly nervous that Ingersoll had inadvertently sent Geisel off to his doom. When Geisel heard this, it amused him no end. “Breakthrough at Front,” he wrote a few days later in his journal. “Harris and Ingersoll search for my body for four days.” Eldredge recalled in an unpublished memoir that it was three months before he and Ingersoll received a “caustic” letter from Geisel saying he had “turned around and went like hell for the rear and safety.” Recalling that this all began with Ingersoll offering to send Geisel to a quiet spot in the line, Eldredge mused, “We wondered how quiet Dr. Seuss found it?”

If Geisel did have an encounter with the Ghost Army, it is too bad that he never wrote about it. What fun the man who created The Cat in the Hat, Green Eggs and Ham and How the Grinch Stole Christmas could have had with a band of soldiers working to fool the enemy with inflatable tanks, sound effects and play-acting. “And to think,” he might have written, “that I saw it in Luxembourg.”

Rick Beyer is an author and filmmaker. He came across this story while researching his 2013 documentary, The Ghost Army, which tells the story of the deception troops that used inflatable tanks and sound effects to fool the Germans.