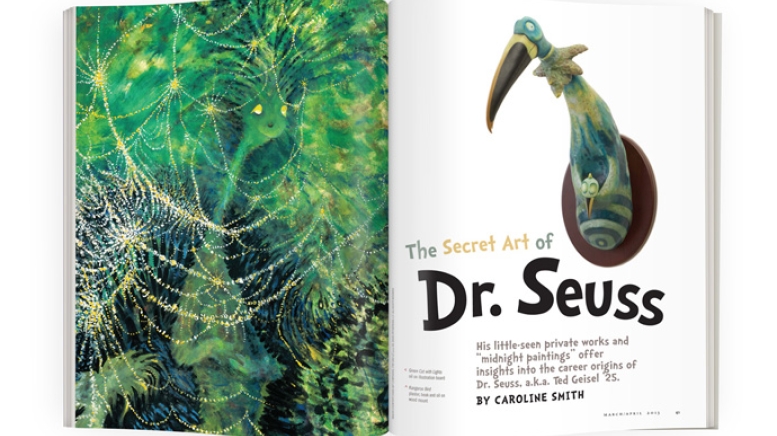

Illustrator by day, surrealist by night, Ted Geisel created a body of irrepressible work during his leisure hours that he called his “midnight paintings.”

For 60 years what’s become known as his Secret Art allowed Geisel to expand his artistic boundaries without the confines and pressures of commercial deadlines and influences. These paintings afforded the peaceful distraction that he craved, and the tenets of surrealism—surprise and juxtaposition—could not have energized his sensibilities more. The result was an artist letting his mind and palette wander in a way that simply was not possible in most of his work-for-hire assignments.

It was inevitable, however, that he would discover things in his private works that would often find their way back into his commercial projects. These paintings became a breeding ground for some of his most beloved icons. The Secret Art canvases also provided a new repository for him to take the characters and landscapes he had developed commercially and realize them in a new context, one in which the world of adult play took center stage. Here it is as if the grand characters of Seuss’s performances have stepped off that stage, sloughed off their makeup and sat down to enjoy a few cocktails after the show.

Although Geisel wanted to protect his Secret Art from criticism, he always intended for the work to be seen when he was gone. If his labor in children’s literature was the heart of the man, this work was his soul.

The zoo in Springfield, Massachusetts, was a beloved part of Geisel’s childhood. When his father, who was appointed to an honorary position on the parks board in 1909, wasn’t able to accompany him and his sketchpad there, he would go with his mother or his sister Marnie. Early on Geisel’s mother became his “accomplice in crime,” encouraging him to draw animal caricatures on the plaster walls of his bedroom. Only later, when his father became the superintendent of the parks, did he also become an unexpected resource who aided and abetted his son’s artistic efforts. Zoo animals that had met their demise lived on as their bills, horns and antlers were shipped to Geisel’s New York City apartment to become exotic beaks and headdresses on his bizarre taxidermy sculptures.

In 1938 Geisel’s classmate Paul Jerman ’25 wrote a brief biography of him. “Another iron in the fire is what the doctor himself calls The Seuss System of Unorthodox Taxidermy,” he wrote. “Not satisfied with drawing strange beasties, Geisel modeled the heads of some of his animals, mounted them and put them on display in bookshops around New York to promote And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. Many people wanted to buy the weird animal heads.”

The surprising enthusiasm for Geisel’s early taxidermy pieces encouraged him to cialis online try selling them by mail via an advertisement in the April 1938 Judge magazine. It was headlined “Extra! Extra! Dr. Seuss Returns from the Bobo Isles…with Rare and Amazing trophies for the Walls of your Game-Room, Nursery or Bar!” One piece was the Blue-Green Abelard ($15): “Approximately two feet tall. The beautifully convoluted horns of the Abelard make it an ornament that will lend distinction to any room.” Another was the Mulberry Street Unicorn ($3.75): “The Unicorn seems to do nothing but just sit and think. About what, no one knows. One can only eliminate certain thoughts as improbable, such as thoughts about xylophone, zippers and Zog of Albania.” A third piece, the Tufted Gustard ($4.75): “For the first forty years of his life, his tuft is in the awkward stage. He hides…and does not emerge until late middle life when his tuft, at last, breaks into full bloom.”

Drawing was innate for Geisel. He doodled on notepads all the way through high school and college, and when he and his sister Marnie were young, he even drew a mural of “crazy animals” in her bedroom between wallpaperings. His black loose-leaf Oxford notebook is now an archived piece of ephemera, whose 68 pages are mostly pen-and-ink cartoons. Precious few pages have lecture notes.

At the University of Oxford, “Anglo-Saxon for Beginners” was the class he shared with Helen Palmer, who would become his wife in 1927. Bemused by Geisel’s wandering mind and fascinated by his drawings, one day she caught him illustrating John Milton’s Paradise Lost by sketching the angel Uriel sliding down a sunbeam, oiling the beam along the way with a tuba-shaped can. “You’re crazy to be a professor,” she told him after class. “What you really want to do is draw.”

Geisel was only 23 when he traveled from Springfield to New York City looking for his big break. He wrote to friend Whit Campbell ’25 on April 15, 1927, from the Hotel Woodstock: “I have tramped all over this bloody town and been tossed out of Boni & Liveright, Harcourt Brace, Paramount Pictures, Metro Goldwyn, three advertising agencies, Life, Judge, and three public conveniences.”

Three short months later his first professional sale, a cartoon The Saturday Evening Post purchased for $25 and published on July 16, 1927, was all the encouragement he needed to pack his bag and board the train back to New York.

Adapted with permission from Dr. Seuss: The Cat Behind the Hat, copyright © 2012 by The Chase Group, LLC (Chicago).