Moving Pictures

Robert Dance was just a few years out of Dartmouth and starting to put together a photography collection when he wandered into the Witkin Gallery in Manhattan. Thumbing through a bin, he came across a striking, 11-by-14, black-and-white photo of Greta Garbo wrapping herself in a satin robe. The photographer’s name was stamped on the back: Ruth Harriet Louise.

“How much?” Dance asked the proprietor, Lee Witkin.

A hundred dollars.

Who is Ruth Harriet Louise?

Don’t know.

How can you charge $100 for a photograph by someone you don’t know?

Because it’s beautiful.

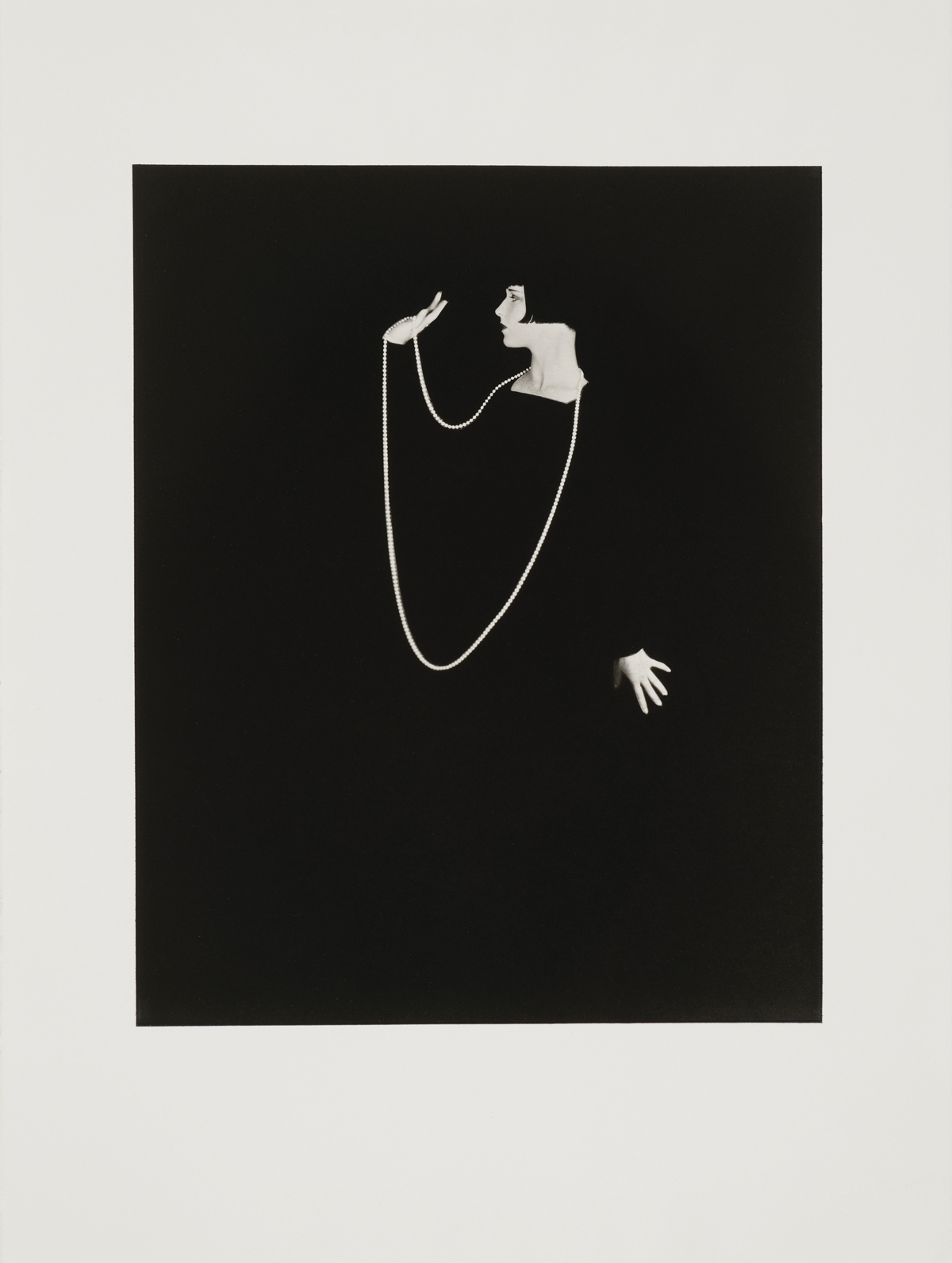

So Dance bought it, launching a lifelong excursion into the world of old Hollywood that’s about to have two resounding payoffs. This February the Hood Museum will mount an exhibition of prized old Hollywood photographs acquired from a collection amassed by the late movie historian John Kobal. Dance, a former chair of the Hood board, served as impresario behind the acquisition, which totals more than 6,000 pieces. “There is an art to these photographs,” says the Hood’s grateful director, John R. Stomberg. “Some are just astoundingly beautifully composed, complicated, rich images that are both aesthetically charged and contextual to the film.”

In November, Dance will publish his latest book, The Savvy Sphinx: How Garbo Conquered Hollywood. “It’s the story of how someone becomes the biggest star ever and then leaves at 36,” Dance says. The book will include photos of Garbo from Dance’s own 1,500-piece collection of old Hollywood photos.

Both the exhibit and the book reflect a Hollywood that has long passed away, an era when the major studios dominated all aspects of the business and employed photographers to promote the stars and their movies. “They were great photographers who had the best cameras, the best papers, the biggest budgets,” Dance says. “They were able to do things quite spectacularly.” The huge cameras used 8-by-10 negatives, yielding oversized 11-by-14 images that were distributed throughout the world and reprinted in reduced size in magazines, newspapers, and promotional flyers. Most of the iconic photos of stars of that era—Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Bette Davis, and countless others—came from this arrangement.

By the time the studio system broke up in the 1950s and 1960s, the role of photographers had declined and the studios cared little about the bulky archives. Some were sold, others literally dumped. Works by top-tier photographers—Louise, George Hurrell, Clarence Sinclair Bull among them—began to disappear. Kobal recognized the art and history in these images and began collecting them in the mid-1960s. When he died in 1991, the John Kobal Foundation owned thousands of photographs.

A few years ago, when the foundation decided to focus on supporting young photographers, it decided to sell the archive in bulk. Through his work as a movie historian and collector, Dance had joined the Kobal Foundation board in 2005 and helped broker the deal that brought the bulk of the collection to the Hood at a steep discount. (Hood officials will not comment on the value of the collection, but individual vintage Hollywood prints can sell for upwards of $5,000.) The history embedded in the photographs should be a trove for the film studies department as well as students in other fields, Dance points out.

Photography historian Colin Westerbeck maintains that vintage Hollywood photos lack the “friendly tension” between photographer and subject that marks much of the most celebrated portrait photography. The studio photographers were “not seeking the inner truth of someone’s character,” says Westerbeck, a former curator of photography at the Art Institute of Chicago. Still, they created otherworldly beauty.

Fiction—or at least legend—is at the heart of Dance’s new book about Garbo. His take is startling: “There was nothing about her that was interesting. Absolutely nothing—except the fact that she was the most beautiful woman who ever lived and maybe the greatest actress.”

Dance’s book is not a biography but an examination of the creation of her image. From a lower working-class family in Stockholm, poorly educated, discovered in a Swedish movie, Garbo landed in Hollywood intensely introverted and unable to speak English. But from the start she had a relationship “with the camera that can only be described as magic,” Dance says. She refused to do the contractually obligated publicity, but “studios figured out pretty quickly that they could turn this into a gimmick. Her personality then became a marketing ploy.” MGM worked the iconic Garbo line into the script for Grand Hotel: “I want to be alone.”

Dance’s Hollywood connections go back to his days at Dartmouth, when he took courses with the film studies professor Maurice Rapf ’35, son of Harry Rapf, a founding producer at MGM. “I was sort of a disciple of Maury’s, I took all his classes,” says Dance. This was well before film studies grew into its own department. In those days film classes functioned as “sort of an interesting enrichment,” says Dance, who majored in art history.

After college Dance earned a master’s in religion at Yale, then moved to New York and soon set up a business as a private art dealer specializing in Old Master drawings. Today he’s largely retired from art dealing and divides his time between Manhattan and rural Connecticut—with occasional visits to Hanover to help organize the Kobal photographs.

Dance, 66, remains immersed in old Hollywood by working on another book, a biography of Joan Crawford. Unlike Garbo, Crawford led a life full of interesting moments. “She arrived in Hollywood and couldn’t dance, couldn’t act, a little overweight, not very attractive,” Dance says. “And the rest is history.”

RICHARD BABCOCK is a novelist and former editor of Chicago magazine. Photos courtesy Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth: The John Kobal Foundation Collection (Purchased through the Mrs. Harvey P. Wood W’18 Fund)